Informed Immunity: Are All Vaccines Necessary? (Part 3/3)

Vaccines are hailed as one of the greatest advancements in public health, but are all the recommended shots truly essential? Let's look at the data.

Vaccines are everywhere—from your baby’s first doctor visit to routine boosters as adults. They’re touted as life-savers, hailed as one of modern medicine’s biggest breakthroughs. But here’s the big question: Are all vaccines really necessary? Or are we taking shots in the dark, trusting a system that might need a second look?

The journey of vaccines started small, with just a few essential immunizations. Over time, the schedule grew, adding more and more shots, each claiming to shield us from diseases. Yet, as the list of recommendations expanded, so did concerns. Today, with dozens of shots on the roster—and debates raging louder than ever—it's fair to ask: Are we prioritizing public health, or are we overreaching?

In this article, we’re diving headfirst into the evolution of vaccine schedules, tracing how they ballooned from a handful of recommendations to the extensive list we have today. We’ll tackle mortality data for diseases in the current schedule (spoiler: some are almost extinct), and we’ll unpack the controversy around the COVID-19 vaccine—its technology, its injuries, and its place in history.

But this isn’t about scaring you. It’s about empowering you.

Doctors can make mistakes. Governments don’t always get it right.

It’s up to you to take charge of your health, to ask the hard questions, and to keep your eyes open when the loudest voices demand your trust. As the philosopher Denis Diderot once said:

“Skepticism is the first step toward truth.”

A Brief History of Vaccine Recommendations

Vaccines didn’t always dominate the healthcare conversation. In fact, the first recommended vaccine schedules were far from what we see today.

The First Vaccine Schedule

The first official vaccine recommendation emerged in the 1940s, focusing on just a few life-threatening diseases. Smallpox, diphtheria, and tetanus were the main culprits being tackled. The schedule wasn’t extensive because the medical field was still figuring out how to mass-produce vaccines effectively.

At this time, children received a smallpox vaccine early in life and a diphtheria-tetanus shot. The simplicity reflected the priorities of the era: address the deadliest diseases first.

Expanding the List Over Time

1950s–1960s: Tackling Polio and Measles

The introduction of the polio vaccine in the 1950s marked a turning point. Jonas Salk’s inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) became a public health triumph, eradicating the disease in the U.S. by the 1970s. Measles vaccines followed in the early 1960s, drastically reducing cases and saving lives.

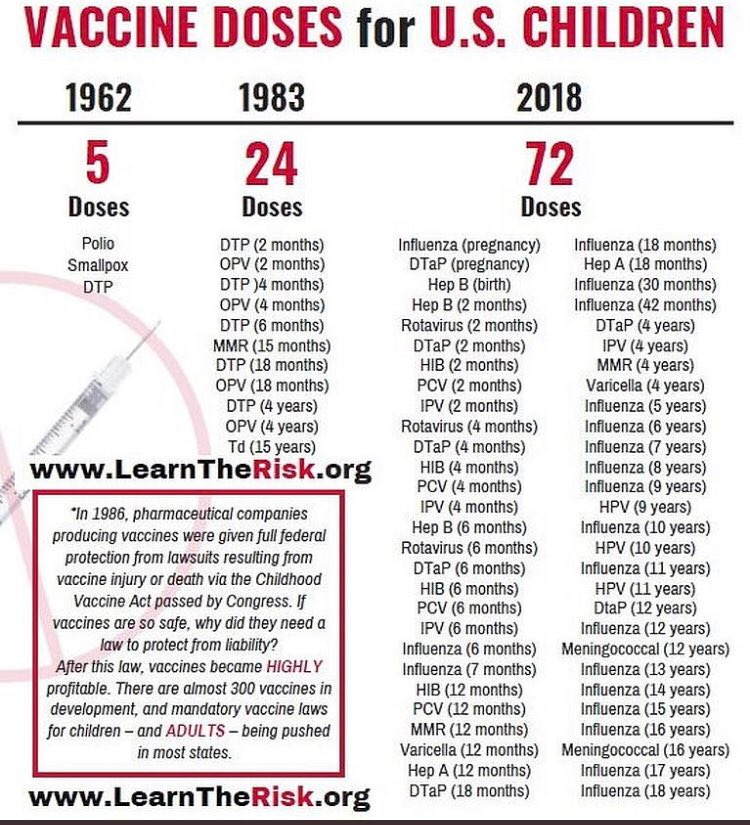

In 1962, there were 5 doses that were recommended in relation to the following:

Polio

Smallpox

DTP (Diptheria)

1970s-1980s: The MMR Vaccine, Hep-B, and Hib

The 1970s brought the MMR vaccine, a combination shot protecting against measles, mumps, and rubella. By bundling vaccines, healthcare providers reduced clinic visits and improved compliance, ensuring everyone got all three.

The Hepatitis B vaccine debuted in the early 1980s, aimed at protecting against a virus linked to liver failure and cancer. By the end of the decade, the Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b) vaccine was added to combat bacterial meningitis.

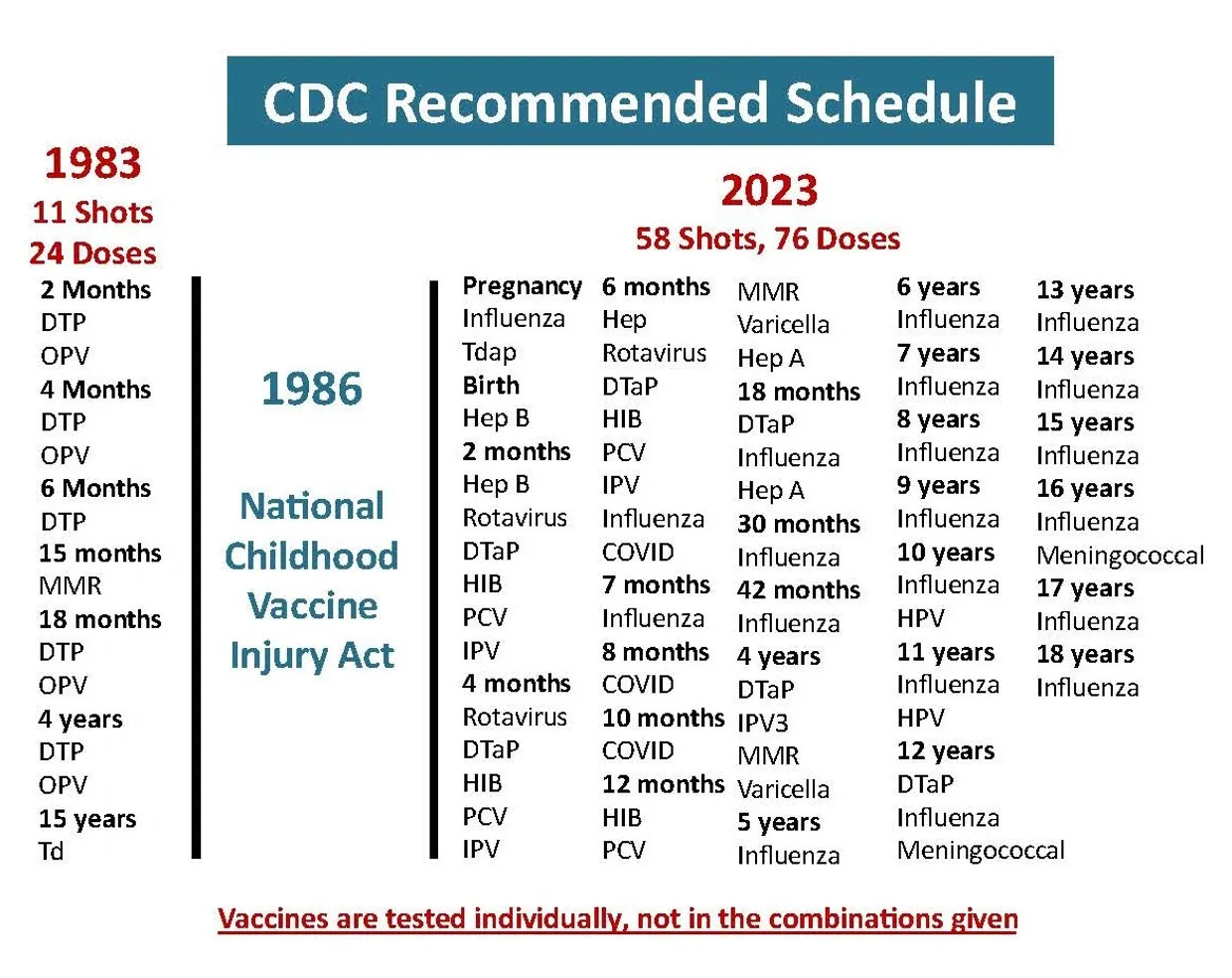

In 1983, the 5 doses had grown to 24 doses:

DTP (2 months)

OPV (2 months)

DTP (4 months)

OPV (4 months)

DTP (6 months)

MMR (15 months)

DTP (18 months)

OPV (18 months)

DTP (4 years)

OPV (4 years)

Td (15 years)

1990s–2020s: Varicella, Rotavirus, and Beyond

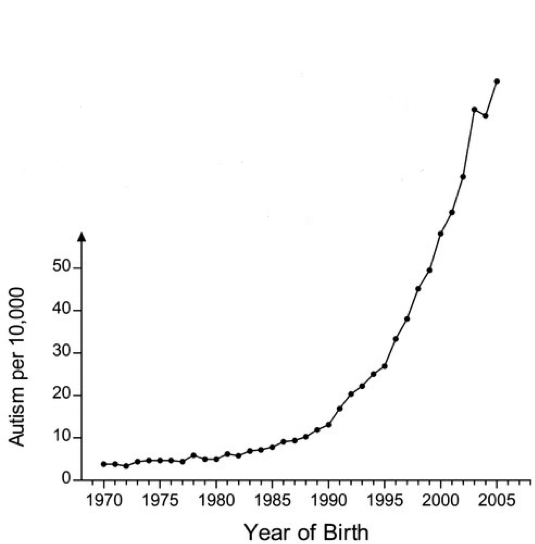

Over the next 30 years, the number of recommended vaccines ballooned. This followed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 (NCVIA) which protected pharmaceutical companies from liability in relation to vaccine injuries. The chickenpox vaccine was introduced in 1995. Between 1998-2006, the rotavirus vaccines were developed. In the 2010s, HPV and Meningococcal vaccines were added.

By 2018, the vaccine schedule was now 72 doses.

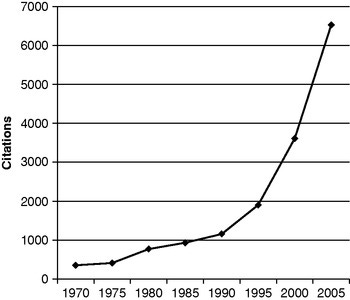

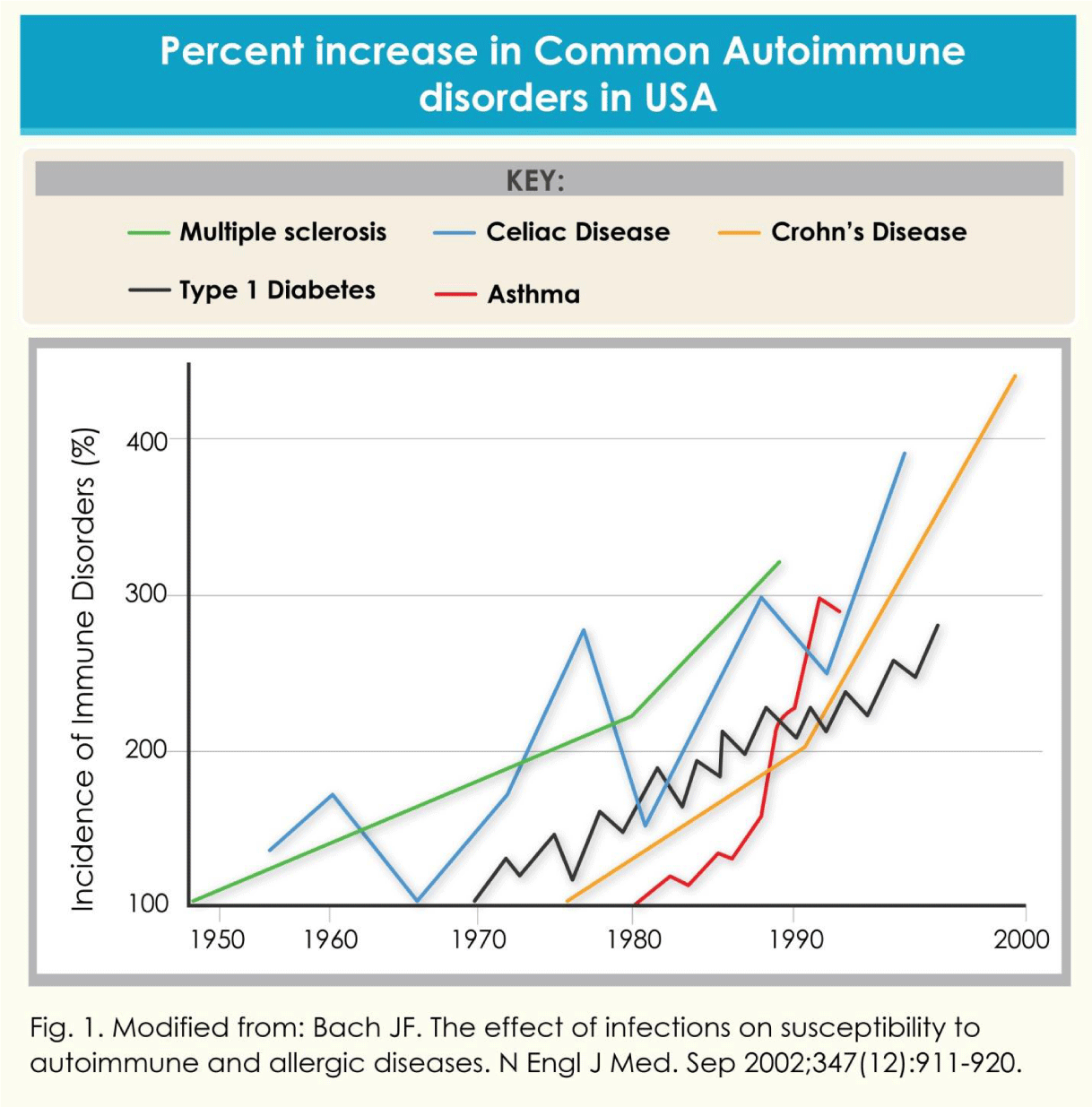

In relation to this chart, it’s important to look at other charts. You decide if there’s a connection:

While our food and diet is likely a contributing factor to these charts, they cannot be blamed alone.

Today’s Expansive Schedule

Now, the vaccine schedule includes over a dozen immunizations for children, adolescents, and adults. From flu shots to COVID-19 boosters, the list keeps growing. But with each addition, questions arise:

How necessary are these vaccines?

Are they really worth the risks and costs?

Illnesses Targeted by the Current Schedule

Vaccines are designed to prevent some of the most debilitating and deadly diseases known to humanity. But when was the last time you encountered an American with polio? Is it that the disease has gone away or is everyone taking the polio vaccine? Or is it herd immunity?

Death Rates from Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Measles

Before the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963, approximately 500,000 cases and 400–500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. While the disease was highly contagious, death rates dropped significantly. By the early 2000s, measles was declared eliminated in the U.S., with most cases now linked to international travel.

Yet, the CDC still recommended children get 2 MMR vaccine doses, once between 12-18 months and again between 4-6 years.

Polio

Polio was a devastating disease in the early 20th century, causing paralysis in 15,000 people annually in the U.S. before the vaccine's introduction in 1955. The last naturally occurring polio case in the U.S. was reported in 1979. However, global eradication efforts are ongoing, with isolated outbreaks still occurring in under-immunized regions.

Yet again, the CDC still recommends that children get 4 IPV vaccine doses: 2 months, 4 months, 6-18 months, and 4-6 years.

Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

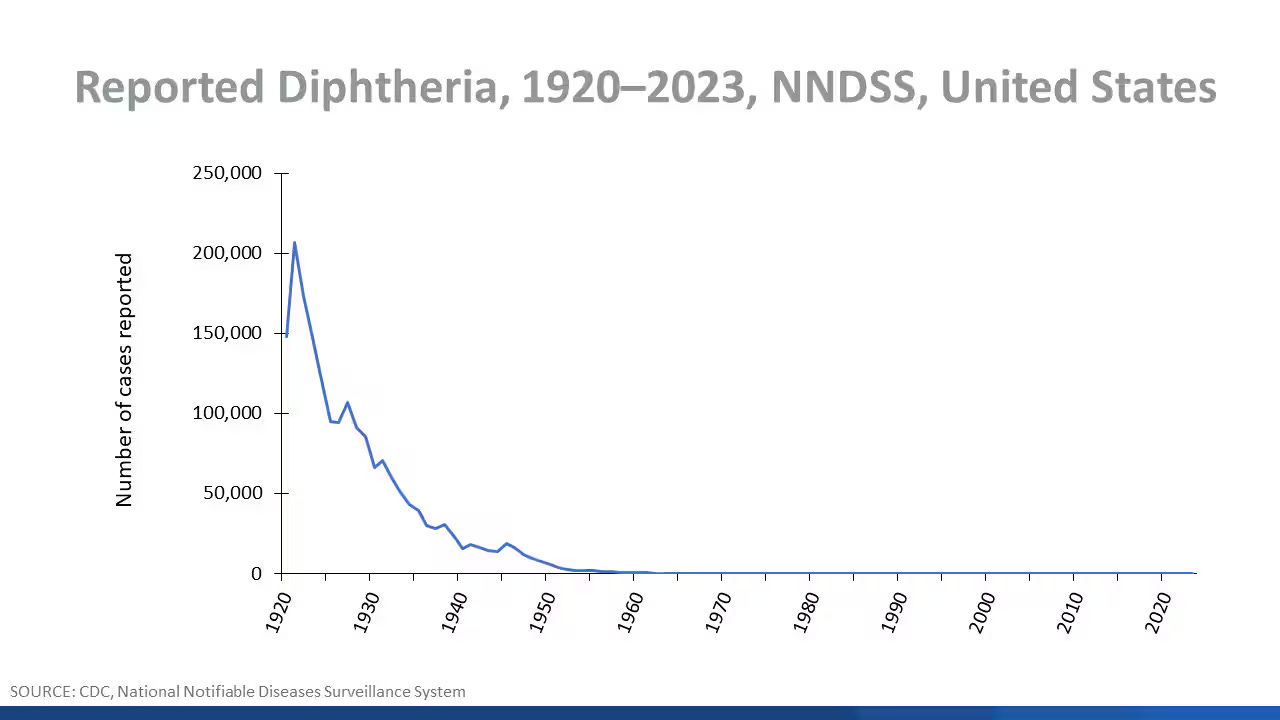

Diphtheria: Pre-vaccine mortality rates were as high as 15,000 deaths per year in the 1920s in the U.S. Today, cases are virtually nonexistent. The last U.S. case of confirmed respiratory diphtheria was in 1997.

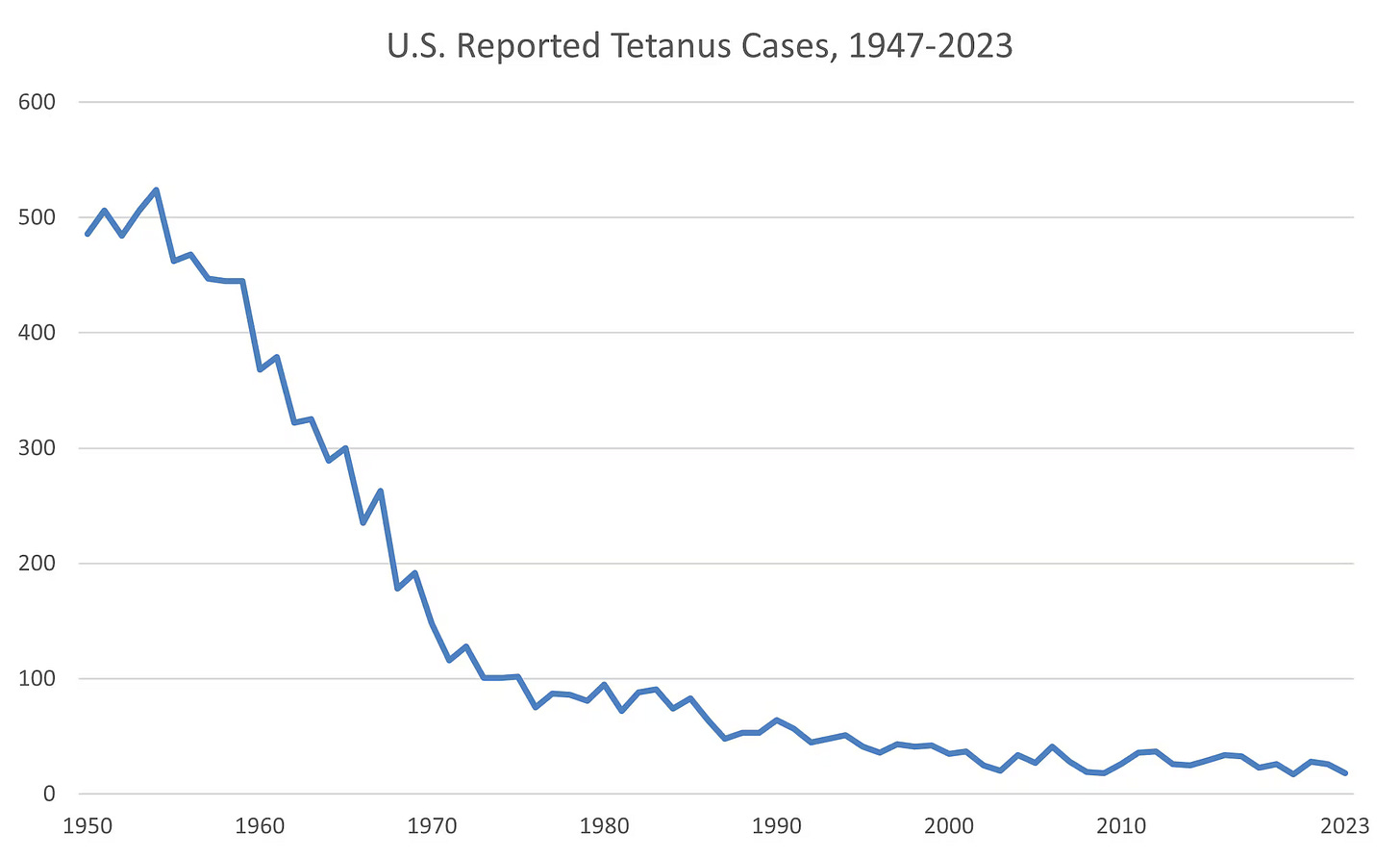

Tetanus: Known as “lockjaw,” tetanus caused 600–800 deaths annually in the early 1900s. While rare today, it remains a concern in “under-vaccinated” areas or for those with severe injuries. Since 2000, there have been less than 50 reported cases each year. Most cases are in adults.

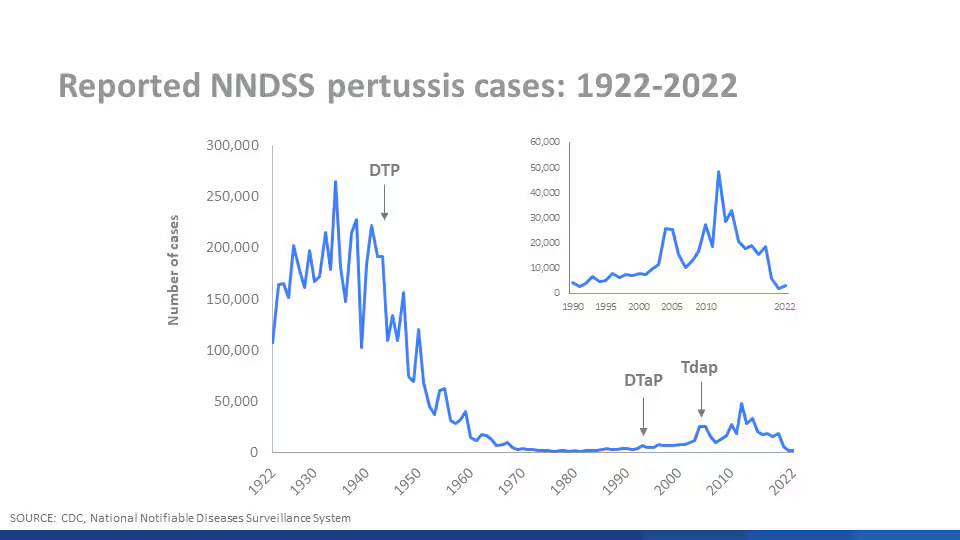

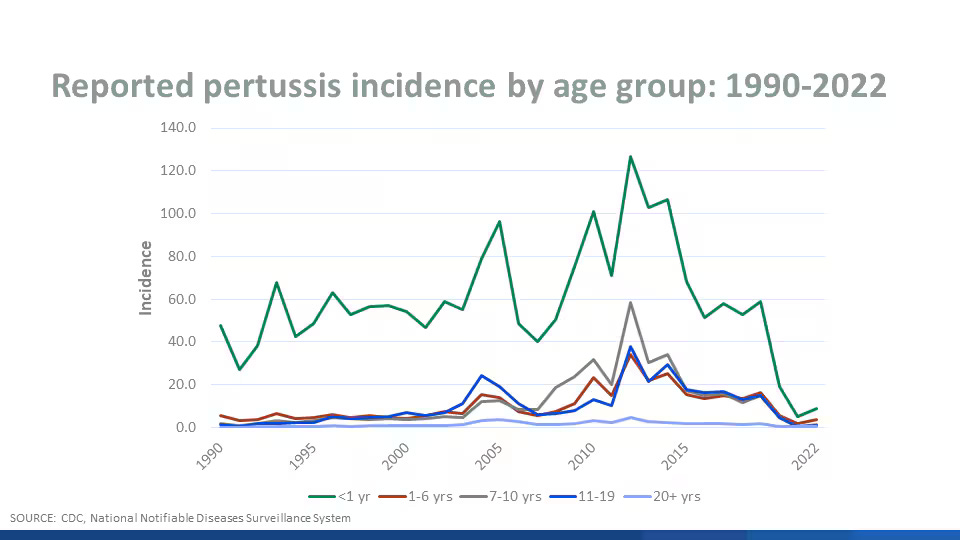

Pertussis: Whooping cough remains a threat, with cyclical outbreaks causing thousands of cases annually, even among vaccinated populations. While the disease rarely leads to death, it poses a greater risk to infants under six months old and also has the highest reported rate of pertussis.

This last chart looks pretty scary for children under a year old. But how bad is pertussis. Let’s look at the CDC’s Pertussis Surveillance Report from 2023.

2 deaths for kids under a year old. 3 total. Out of 729 cases for kids under a year old and 5,611 total. Saving you the math, that’s 0.3% (about a third of 1%) and 0.05% (about 1/20th of a percent), respectivally.

So, even the most vulnerable group, has a 99.7% chance of survival if they catch it.

So let’s look at DtAP collectively:

Diphtheria - Non-existent now.

Tetanus - Extremely rare in children.

Pertussis - Most vulnerable group has 99.7% survival rate.

Yet this 3-dose series is given at 2, 4, and 6 months, followed by boosters at 15-18 months and 4-6 years. Then Tdap (same thing, but stronger for adolescents and adults) is recommended once at age 11-12 and then every 10 years thereafter.

So, by the time a child is 12, they will have had 6 doses of a 3-dose series (18 doses).

Is it still necessary?

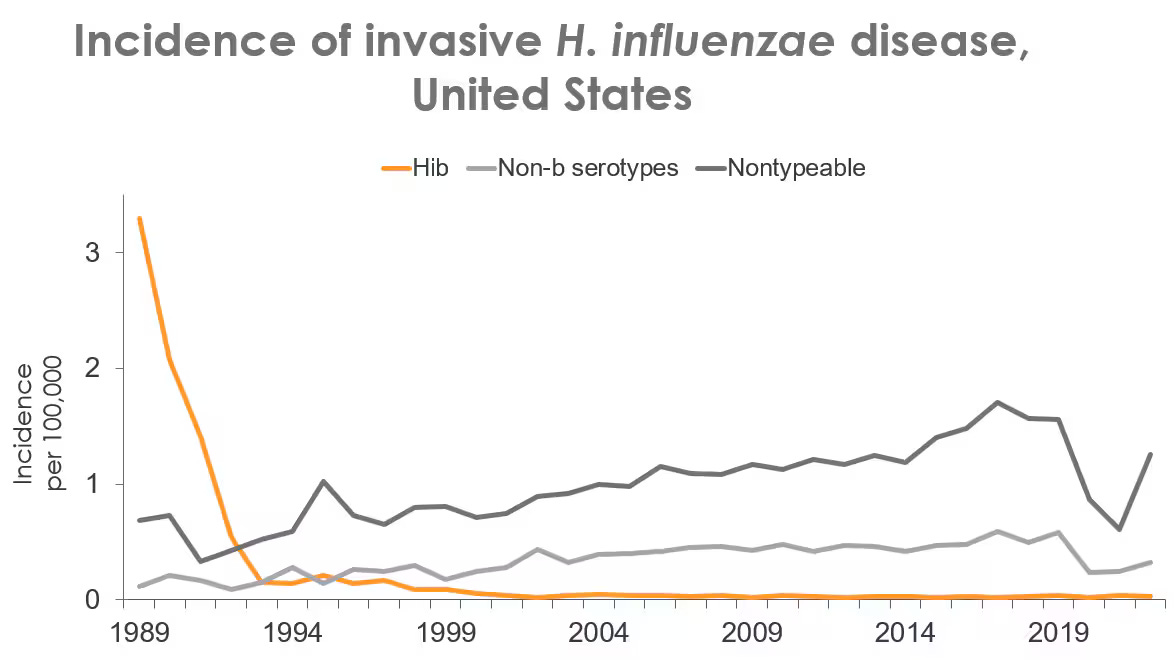

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

Hib was a leading cause of bacterial meningitis and pneumonia in children under five before the vaccine became available in the 1980s. Annual deaths in the U.S. reached 20,000 cases, with a significant decline afterward.

The following groups are at increased risk of invasive H. influenzae disease:

Children younger than 5 years of age

Adults 65 years or older

American Indian and Alaska Native people

Between 3% to 6% of Hib cases in children are fatal. The CDC also points out that “Hib disease is no longer common.” Since 1985, the incidence of invasive Hib disease in children less than 5 years of age has decreased by 99%, to less than 1 case per 100,000 in children younger than 5 years of age.

Chickenpox (Varicella)

While the chickenpox vaccine significantly reduced cases and complications, the disease was rarely fatal for healthy children. Before vaccination, chickenpox caused approximately 100 deaths annually in the U.S., primarily among adults or individuals with weakened immune systems.

Again, more scary numbers. Let’s break it down though, looking at the high end:

4 Million cases. 0.33% (a third of a percent) were hospitalized. 0.004% died. That’s 4/1000ths of a percent or 1 out of 25,000.

CDC recommends 2 doses of varicella vaccine: first dose at age 12 through 15 months and the second dose at age 4 through 6 years old.

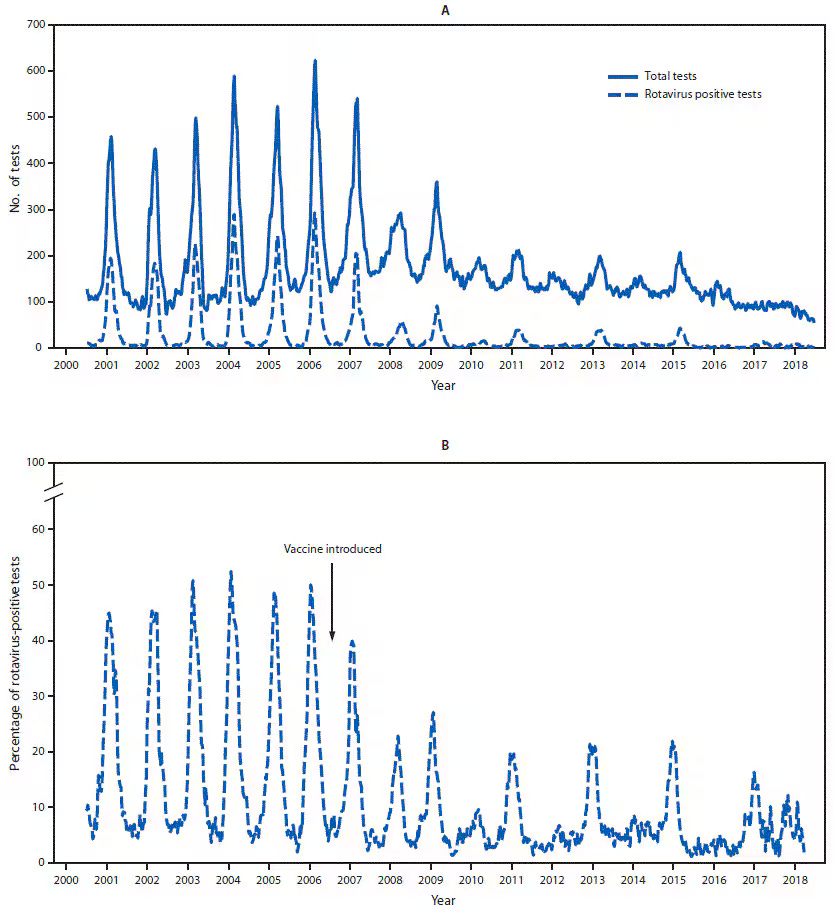

Rotavirus

Rotavirus vaccines were introduced in the late 1990s to prevent severe diarrhea, particularly in young children. While rotavirus-related deaths are rare in developed countries, it remains a leading cause of death in low-income nations due to limited access to clean water and medical care.

Like the flu and pertussis, rotavirus is cyclical.

Rotavirus causes more than 125 million cases of diarrhea each year in children and infants worldwide. In the United States, the number of childhood deaths from rotavirus is between 20 to 40 each year (compared to 600,000 worldwide).

Most children will be infected by the time they are 3. It usually spreads from fecal-oral contact. (two words you don’t want to hear together)

About one out of every 40 children may develop severe enough dehydration to require hospitalization. This amounts to around 55,000 hospitalizations each year. So, let’s break it down.

Between 0.036% and 0.073% of hospitalized cases result in death. That’s between 1 out 2,750 and 1 out of 1,375.

Between 0.00091% and 0.0018% of all rotavirus cases result in death. That’s between 1 out of 110,000 and 1 out of 55,000.

CDC recommends 3 doses at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months.

THE WORST CASE SCENARIO

If a child were to catch every disease associated with these vaccines. What would it look like:

Disease-by-Disease Survival Rates:

Measles: 99.9%

Polio: 95%

Diphtheria: 90%

Tetanus: 85%

Pertussis (Whooping Cough): 99.7%

Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b): 95.5%

Chickenpox (Varicella): 99.996%

Rotavirus: 99.9985%

If you multiply all those together, the child has a 69% survival rate.

Obviously, any sane parent would not want their child to have a 30% chance of dying. But, there’s a few things that need to be accounted for:

Measles has fewer than 125 cases per year.

Polio has 0 cases.

Diphtheria has less than 1 case per year.

Tetanus is exremely rare.

Whooping Cough (pertussis) has between 15,000-25,000 per year.

Hib has fewer than 1 case per 100,000 children under 5.

Chickenpox has fewer than 300,000 cases per year (most of them mild)

Rotavirus accounts for 55,000 hospitalzations per year.

The chances of catching all these diseases (excluding polio):

Example Probabilities (Assumptions Based on Current Data):

Measles: ~125 cases/year ÷ 330 million U.S. population ≈ 0.00004% (1 in 2.64 million).

Diphtheria: <1 case/year ≈ 0.0000003% (1 in 330 million).

Tetanus: ~50 cases/year ≈ 0.000015% (1 in 2 million).

Pertussis: ~20,000 cases/year ÷ 330 million ≈ 0.006% (1 in 16,500).

Hib: ~1 case/100,000 children ≈ 0.001% (1 in 100,000).

Chickenpox: ~300,000 cases/year ÷ 330 million ≈ 0.09% (1 in 1,100).

Rotavirus: ~55,000 severe cases/year ≈ 0.016% (1 in 6,000).

The probability is astronomically low, likely on the order of 1 in several quadrillion.

Context Matters: The Role of Modern Medicine

Vaccines were not the savior of mankind. Many of these diseases saw significant declines in mortality rates before vaccines became available, thanks to:

Improved sanitation and access to clean water.

Antibiotics and advanced medical care.

Public health education, reducing the spread of infections.

Are We Over-Vaccinating?

While vaccines have undoubtedly saved millions of lives, some argue that not all diseases warrant universal vaccination, especially in countries with low infection rates and advanced healthcare systems.

Dr. Peter Doshi, a vaccine policy researcher, argues: “The question isn’t whether vaccines save lives—they do. It’s whether every vaccine for every disease is necessary for everyone.”

Countries like Germany and the United Kingdom have begun to re-evaluate their recommendations, limiting vaccines like rotavirus to high-risk groups rather than universal administration. This raises an important question:

Should vaccines in the U.S. follow a similar selective approach?

However, while these vaccines have been in the public eye for longer, one vaccine has recently dominated the headlines.

COVID-19 and the New Era of Vaccines

COVID-19 changed the world in ways that few other public health crises have. It disrupted economies, lives, and societal norms. It also ushered in a new era of vaccine technology, sparking both praise and controversy. The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines introduced innovations like mRNA technology, but it also raised important questions about safety, effectiveness, and the future of immunization programs.

The Rise of mRNA Vaccines

The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines became household names as the first mRNA-based vaccines authorized for widespread use.

But what makes mRNA vaccines so revolutionary?

How They Work: Unlike traditional vaccines that use weakened or inactivated viruses, mRNA vaccines provide cells with genetic instructions to produce a harmless piece of the virus (the spike protein). This triggers an immune response without exposing the body to the live virus.

Speed of Development: The ability to design mRNA vaccines quickly played a key role in their rollout. While traditional vaccines can take years to develop, mRNA platforms allowed scientists to produce vaccine candidates in mere weeks.

Effectiveness: Early data showed that mRNA vaccines were 95% effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19, a figure that surpassed expectations.

Sounds great! But as the saying goes, “If it’s too good to be true…”

Concerns about the long-term effects of mRNA vaccines has quickly risen, given the relatively short clinical trial periods compared to traditional vaccines. So, vaccine seekers were given an alternative.

Adenovirus-Based Vaccines: The Johnson & Johnson Alternative

The Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine offered a more traditional approach using adenovirus-based technology. Unlike mRNA vaccines, it uses a modified virus (not COVID-19) to deliver instructions to the body. Initially hailed for requiring only one dose, the J&J vaccine was appealing.

However, this didn’t last long.

Reports of serious side effects, such as blood clots (thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome) led the FDA to recommend its use only for those unable to take mRNA vaccines.

By April 21, 2021 (about 2 months after being approved) nearly 8 million doses of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine had been administered.

The Israeli Study: Waning Immunity and Booster Shots

One of the most cited studies on COVID-19 vaccines came out of Israel, one of the first countries to achieve high vaccination rates. The study revealed two key findings:

Waning Immunity: Vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic infection dropped significantly six months after the second dose, necessitating booster shots.

Breakthrough Cases: While vaccinated individuals were said to be less likely to experience severe illness, breakthrough infections underscored the need for continued public health measures.

This study was pivotal in shaping global booster campaigns, but it also reignited debates about vaccine durability and the role of boosters.

More strange (and concerning) was the media’s obsession with pushing the vaccine, as can be seen here:

The Rise of Vaccine Injuries Post-2020

With billions of doses administered worldwide, adverse reactions were expected to occur at a small scale. However, some incidents sparked concern:

Myocarditis and Pericarditis: Cases of heart inflammation were reported, particularly among otherwise healthy young males after receiving mRNA vaccines.

VAERS Reports: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) logged an unprecedented number of reports post-2020. The sheer volume fueled skepticism and calls for greater transparency.

According to the CDC, the benefits of vaccination still far outweighed the risks, but these issues highlighted the need for more thorough post-market surveillance and accountability among the pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Questioning the Necessity of Vaccines

Vaccines have been a cornerstone of public health, credited with saving millions of lives. However, as vaccine schedules expand, questions arise as to whether every vaccine is truly necessary.

Should all children receive the same set of shots, or is there a case for a more selective, individualized approach?

Vaccines, it seem, primarily prevent hospitalizations and inconveniences rather than significant mortality. While this is valuable, it raises the question:

Should the risk of rare vaccine side effects be weighed differently for low-risk diseases?

The Role of Big Pharma and Media

The vaccine industry generates billions annually, raising concerns about conflicts of interest:

Pharmaceutical companies benefit financially from broad vaccine mandates.

Media campaigns often frame skepticism as “anti-science,” potentially stifling legitimate concerns. Additionally, a big portion of their advertisement income comes from pharmaceutical companies.

To quote Mahatma Gandhi:

“Truth never damages a cause that is just.”

A Case for a More Selective Approach

Countries like Germany and the UK have adopted more tailored recommendations, prioritizing vaccines for high-risk groups rather than universal administration. This selective approach acknowledges that not all vaccines carry the same urgency in populations with access to advanced healthcare.

Comparison of Disease Rates and Vaccine Approaches: U.S., Germany, and the UK

Despite having a significantly larger population, the U.S. maintains universal vaccination policies, even for diseases like rotavirus and chickenpox, which cause very few deaths annually. The outcomes are strikingly similar, with all three countries reporting exceedingly low death rates for these diseases.

Conclusion: Taking Responsibility for Your Health

Vaccines have undeniably transformed global health, but they’re not without risks or limitations. The question isn’t whether vaccines work—they do—but whether every vaccine for every individual is necessary. The answer requires careful thought, not blind trust.

Doctors, governments, and pharmaceutical companies can make mistakes. It’s up to each of us to question, research, and advocate for our own health.

Ultimately, you are responsible for your health decisions—not your doctor, not the government, and not the media. Staying informed, asking hard questions, and listening to the data will empower you to make choices that are right for you and your family.