Operation Earnest Voice: The Future of Propaganda (Mockingbird 2.0)

How the U.S. uses advanced tech like deepfakes and AI in Operation Earnest Voice to control narratives and shape public opinion worldwide.

What if the battlefield wasn’t on the ground, but in your mind? That’s the world we live in today, where wars are fought with words, not just weapons. Enter Operation Earnest Voice (OEV). To shape narratives, combat extremist propaganda, and sway public opinion across the globe.

Launched under the radar by the U.S. military, OEV operates in the shadows of the digital world. From creating fake online personas to influencing conversations or creating purely fabricated online debates in regions like the Middle East, this program has one goal: control the story.

What Is Operation Earnest Voice?

Launched in the early 2010s by the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), Operation Earnest Voice (OEV) was designed as a digital counterstrike against “extremist propaganda.”

What is extremist propaganda? Well, it’s a moving target. So whatever fits the bill of terrorism for that day.

To support these efforts, the U.S. government allocated significant resources. OEV’s annual budget reportedly exceeded $75 million, reflecting its strategic importance. Over time, this funding supported the program’s expansion into allied nations’ influence operations, further broadening its reach.

Overall, the goal was to influence perceptions and counter misinformation spread by groups like ISIS and Al-Qaeda (although with the recent events in Syria, it seems like they’re our allies now). OEV aimed to disrupt enemy narratives, amplify “moderate” voices (again, a ‘moving target’ phrase), and sway public opinion in regions like the Middle East.

But its mission didn’t stop there. Beyond silencing extremist propaganda, OEV sought to shape how the U.S. and its allies were perceived. The operation worked to undermine unwanted messaging while promoting narratives that aligned with American and coalition interests.

Methods

OEV’s toolbox included a range of covert and sophisticated methods:

Sock Puppets: Operatives used fake online personas, known as sock puppets, to engage directly with target audiences. These personas blended into online communities, shared counter-narratives, and disrupted unwanted messaging, all while appearing (both online and in the programming) like ordinary users.

Third-Party Validators: The program utilized trusted intermediaries to lend credibility to its messages. By having independent-looking entities endorse or spread U.S.-aligned narratives, the operation enhanced its authenticity and reach.

Secure Communication Systems: Coordination was key. OEV relied on classified platforms to ensure its operatives could collaborate seamlessly without risking exposure (more on this in a bit). These systems protected the operation’s sensitive activities from adversaries’ prying eyes.

By leveraging these tools and resources, OEV became a cornerstone of U.S. digital psy ops. However, as we’ll explore, the operation’s methods and objectives also raised ethical questions.

How It Works: The Tools of Digital Influence

To understand how Operation Earnest Voice (OEV) operates, you need to follow the digital breadcrumbs. At the heart of OEV lies a little-known firm: Ntrepid.

How It Works: The Tools of Digital Influence

To understand how Operation Earnest Voice (OEV) operates, you need to follow the digital breadcrumbs. At the heart of OEV lies a company shrouded in secrecy and intrigue: Ntrepid. This little-known firm, contracted by the U.S. government (to the tune of $2.76 million), is the mastermind behind the software enabling OEV’s operations. For conspiracy theorists, it’s a goldmine of suspicious connections, murky funding, and eyebrow-raising individuals.

The Shadowy Role of Ntrepid

Ntrepid markets itself as a developer of cutting-edge cybersecurity and anonymity tools, but dig a little deeper, and you’ll find it’s not your average tech company. They created Anonymizer, a tool explicitly designed to mask the identities of users online.

The software allows a single operator to control up to 10 personas simultaneously, each with their own detailed backstories, regional accents, and online activity histories. These sock puppets can operate across forums, blogs, and social media platforms to engage with users, spread narratives, and respond to conversations in real-time. This level of sophistication makes it nearly impossible to distinguish the fake from the real.

Also, the operatives are able to operate these personas from different geographic locations through proxy servers, making them appear as though they’re posting from anywhere in the world. The software integrates "traffic mixing," a feature designed to blend user activity with legitimate internet traffic to create "excellent cover and powerful deniability."

That’s a direct quote from Centcom. “Powerful deniability.”

In layman’s terms, Ntrepid's tools can make it look like someone halfway across the world is behind the keyboard, even if the controller is stationed at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida—home of U.S. Special Operations Command.

This isn’t just your run-of-the-mill bot farm.

But here’s where it gets really interesting: Ntrepid’s primary funding.

Ntrepid gets its primary funding from In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture capital arm. That’s right—the company behind OEV’s tools is funded by the U.S. intelligence community.

Coincidence? Hardly.

The People Behind the Curtain

The individuals tied to Ntrepid add another layer of intrigue.

The Founder and Former Chairman of Ntrepid: Richard Hollis Helms

Had a 30-year career in the CIA. He was an Arabist in the Middle East, and Chief of Station or Deputy Chief of Station in various locations including Latin America, Asia, Europe, and the USA. He was involved in intelligence-gathering, clandestine anti-terrorism intel programs, counter-terrorism/counter-narcotics programs, and was allegedly referred to as the "rock-star of the CIA."

He was the former head of the agency's European division before he started Abraxas after 9/11. When he “hired tons of CIA staffers.” He also hired Rod Smith, a former chief of the agency's Special Activities Division, and Fred Turco, one of the original architects of the CIA's counterterrorism center and the former chief of external operations. Meredith Woodruff, one of the agency's most senior female operatives, signed on to Abraxas in 2006. Barry McManus was another hire, who had worked in 130+ countries (he was the CIA's chief operations polygraph examiner and interrogator).

The President of Ntrepid: Charlie Englehart

Charlie worked in support of the Department of Defense and other clients in the national security community. Was previously VP of Abraxas Corp for 6 years (Richard Hollis Helm’s previous company) before becoming VP at Ntrepid. And, it would appear he’s making a pretty penny.

So former intelligence officers and military contractors. These are people who’ve spent their careers involved with covert operations.

And there’s also Lance Cottrell, a cybersecurity expert who was the Founder of Anonymizer (which is now wholly owned by Ntrepid) back in 1995. It basically was the precursor to Tor, for all the “file sharers” from the 2000s who “shared” music. He also created Mixmaster, an open-source anonymous email platform around that same time.

Formerly, he was chief scientist for Ntrepid. He was also, allegedly, the money behind the Cards Against Humanity lawsuit again Elon Musk. (For context, CAH bought U.S.-Mexico border land in order to thwart Trump building a wall).

His patents on proxy routing and secure communication align with OEV’s objectives and are likely what got them the DoD contracts. While his public persona paints him as a privacy advocate, skeptics might wonder whether his tools serve a dual purpose—protecting citizens or enabling mass deception.

From what can be seen online, it would appear that Cottrell couldn’t stand it anymore or started to become suspicious. He started his own startup mentorship program called “Feel The Boot”. But not without giving the DoD what they wanted first.

The Dark Potential of the Tools

The program’s methods weren’t limited to forums or social media. A Stanford Internet Observatory report from 2022 revealed that similar U.S.-based sock puppet campaigns have targeted foreign audiences with sensational rumors—like accusations of organ theft in Iran—raising questions about whether truth was a casualty in these operations.

This is reminiscent of COINTELPRO in the late 1960s when the FBI basically directed salacious rumors to the media in order to discredit or embarrass civil rights leaders.

What makes Ntrepid’s involvement so unsettling is the sheer scope of its software. OEV and Ntrepid represent a slippery slope. Despite the stated goal, the tools and techniques used could easily cross ethical boundaries:

False Flags: With the ability to mask their origins, OEV operatives could create false narratives that implicate adversaries. For example, a campaign might frame a foreign government for spreading disinformation while the U.S. actually pulls the strings. *cough* *cough* Gulf of Tonkin

Domestic Use: Although officially aimed at foreign audiences, the amendment of the Smith-Mundt Act in 2013 blurred the line between foreign and domestic propaganda. Could these tools already be influencing U.S. citizens without their knowledge?

Need I remind you: COINTELPRO. GULF OF TONKIN. OPERATION MOCKINGBIRD.

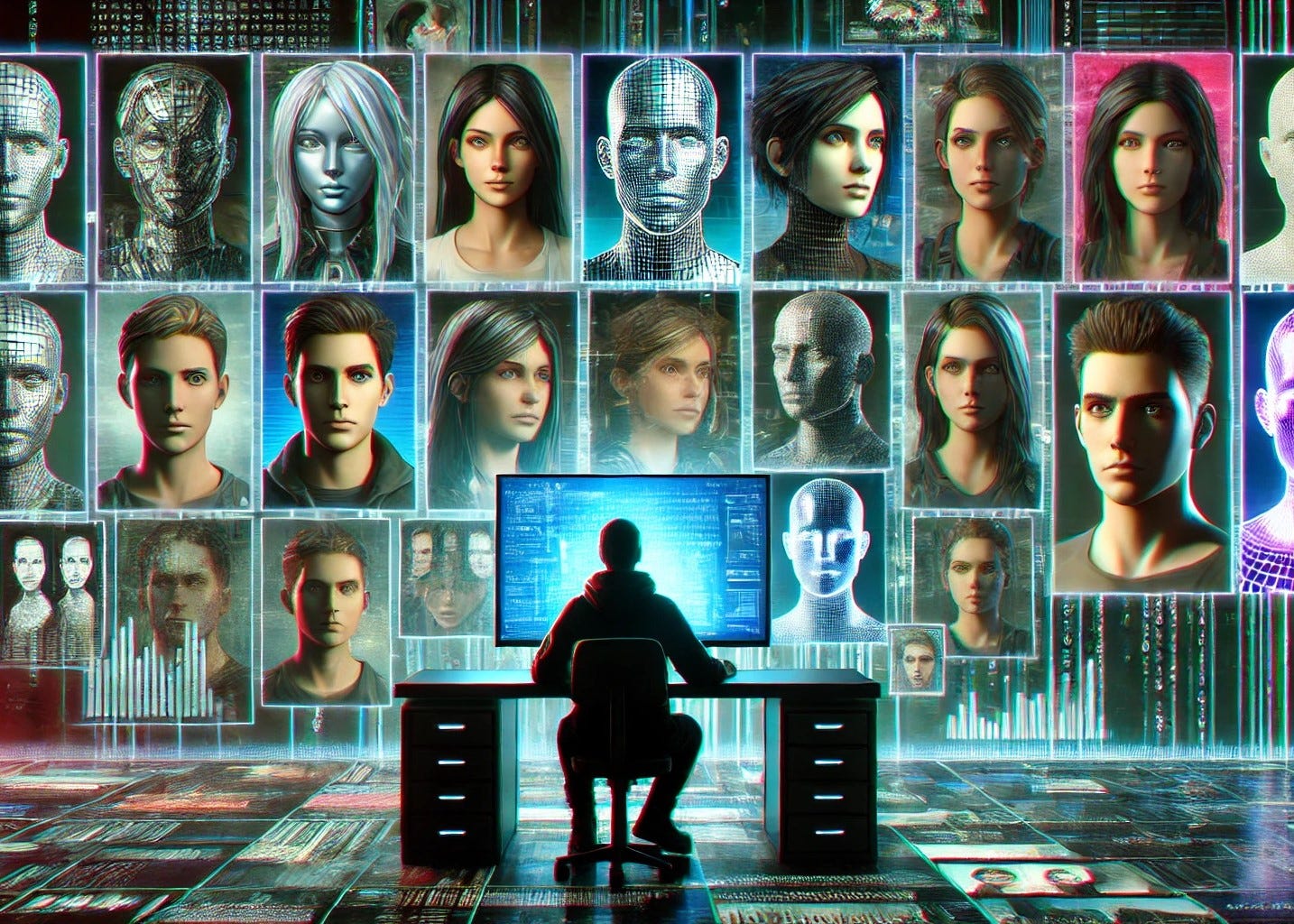

Yes. Yes they are already influencing us.Deepfakes and Disinformation: SOCOM documents from 2022 show a growing interest in tools for digital deception and deepfakes. If combined with OEV’s software, the potential for synthetic narratives, indistinguishable from reality, becomes terrifyingly real. Already, OEV uses these sock puppet accounts to have arguments with themselves, simulating a debate, where the controller is controlling both avatars. Literally controlling the narrative.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN

Let’s call a spade a spade. OEV isn’t just about countering extremists; it’s about shaping global perceptions.

With a $200 million annual budget, as reported in defense spending documents, this operation is no small endeavor. General David Petraeus once described the US military’s objective to be "first with the truth," but whose truth are we talking about?

The secrecy surrounding Ntrepid and OEV fuels speculation that these tools could be used for far more than what’s publicly disclosed. Are we witnessing the next evolution of psychological warfare, where likes, shares, and tweets replace traditional weapons? And if so, how far are we willing to let governments go in the name of national security?

As you’re online, be aware. Information is power and, in a world where perception is reality, don’t let the government tell you what is real or not.

ADDITIONAL INSIGHT: THE TIMELINE OF OEV

2008: Initial Deployment in Iraq

Launch: OEV was reportedly initiated as a psychological operation aimed at countering extremist propaganda during the Iraq War.

Objective: To disrupt the online presence and recruitment efforts of groups like Al-Qaeda by disseminating pro-American narratives.

2010: Expansion to Afghanistan and Pakistan

Regional Focus: The program's operations extended to Afghanistan and Pakistan to address the growing influence of extremist groups in these regions.

Strategic Shift: Emphasis was placed on engaging with local populations to counter insurgent propaganda and support U.S. military objectives.

2011: Contract with Ntrepid

Software Development: The U.S. government awarded a $2.76 million contract to Ntrepid to develop specialized software for OEV.

Capabilities:

Management of multiple online personas ("sockpuppets") by each operator.

Creation of detailed and culturally consistent backgrounds for each persona.

Use of secure VPNs to mask the origin of operations.

Source: The Guardian

2013: Smith-Mundt Modernization Act

Legislative Change: The amendment allowed U.S. government-produced content intended for foreign audiences to be accessible domestically.

Implication: Raised concerns about the potential for domestic dissemination of propaganda materials.

Source: Foreign Policy

2014–2016: Response to Emerging Threats

ISIS Propaganda: OEV adapted to counter the sophisticated online propaganda campaigns of ISIS, focusing on disrupting their recruitment and influence.

Technological Enhancements: Integration of advanced data analytics to monitor and counter extremist narratives more effectively.

2017: Integration with Allied Operations

Collaborative Efforts: OEV operations began coordinating with NATO and allied nations to address global extremist threats.

Information Sharing: Enhanced collaboration facilitated the exchange of intelligence and strategies to combat propaganda.

2019: Budget Allocation

Funding: The U.S. defense budget included allocations for OEV, indicating sustained investment in psychological operations.

2020–2022: Adoption of Advanced Technologies

Digital Deception Tools: Reports indicated that U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) explored the use of deepfakes and other digital deception technologies for psychological operations.

Ethical Considerations: The potential use of such technologies raised concerns about the implications for information integrity and ethical boundaries.

Source: The Intercept

The timeline of Operation Earnest Voice (OEV) and the rapid pace of technological advancements paint a picture of increasingly sophisticated and controversial PSYOPs in the next five years. Here's what the future might hold:

Increased Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI will make sock puppets more realistic and capable of engaging in human-like conversations. Tools like natural language processing (NLP) will enable automated and highly convincing influence operations at scale. This will expand the ability to manipulate public opinion while raising serious ethical concerns about free will and online trust.

Deepfakes and Synthetic Media

Deepfake technology will allow for hyper-realistic videos and audio, making it possible to impersonate public figures or fabricate events. This would allow the spread of disinformation at an unprecedented scale while eroding trust in media and authentic content. Distinguishing truth from fabrication will become increasingly difficult.

Integration with Big Data Analytics

Big data will allow for highly personalized propaganda, targeting individuals based on their behavior and preferences. Real-time sentiment analysis will help operatives adapt strategies quickly, making campaigns more effective. This raises privacy concerns and risks of invasive surveillance.

Automation of Disinformation Campaigns

Automation will enable single operators to manage not a dozen but thousands of bots, flooding platforms with propaganda and overwhelming authentic voices. Content-generation tools will create convincing articles, memes, and videos with minimal human input. Social media platforms would likely struggle to regulate such large-scale disinformation.

Global Competition in Information Warfare

Nations like Russia, China, and Iran will advance their own influence operations, fueling a digital arms race. Decentralized platforms may become new battlegrounds for untraceable propaganda. These conflicts would likely escalate international tensions and disrupt alliances.

Potential Domestic Use and Ethical Concerns

The repeal of the Smith-Mundt Act and blurred boundaries between foreign and domestic audiences could enable indirect targeting of U.S. citizens. Governments might use these tools for public health campaigns or crisis responses, raising ethical concerns about manipulation. Public trust in institutions would suffer as a result (as if it hasn’t suffered enough).

Integration with Emerging Platforms

Psychological operations could expand to immersive virtual reality environments and smart devices, infiltrating daily life. Narratives may be pushed through personalized content in virtual spaces or home assistants. This constant presence of messaging could create an information ecosystem that is both overwhelming and manipulative.