Lines in the Sand: How the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Was Made (1/2)

You’ve heard the headlines. But do you really know how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict started? This isn’t about ancient feuds—it’s about broken promises, colonial greed, and a century of betrayal.

The creation of Israel in 1948 wasn’t just a political moment—it was a tectonic shift. It reshaped borders, upended millions of lives, and ignited a conflict still burning today. But to understand the Israeli Palestine Conflict, you have to dig deeper than biblical prophecy or modern headlines. You have to ask: What really led to the creation of Israel?

And the answer?

It’s messy.

It’s modern.

And it begins long before 1948.

Let’s Be Clear—This Isn’t About the Bible

While the Holy Land sits at the heart of three world religions, the Israeli Palestine Conflict is not a holy war. It's not about scripture.

It's about survival, identity, and the brutal tides of history.

And it begins not in Jerusalem’s ancient stones, but in the ghettos of Europe and the ashes of Jewish suffering.

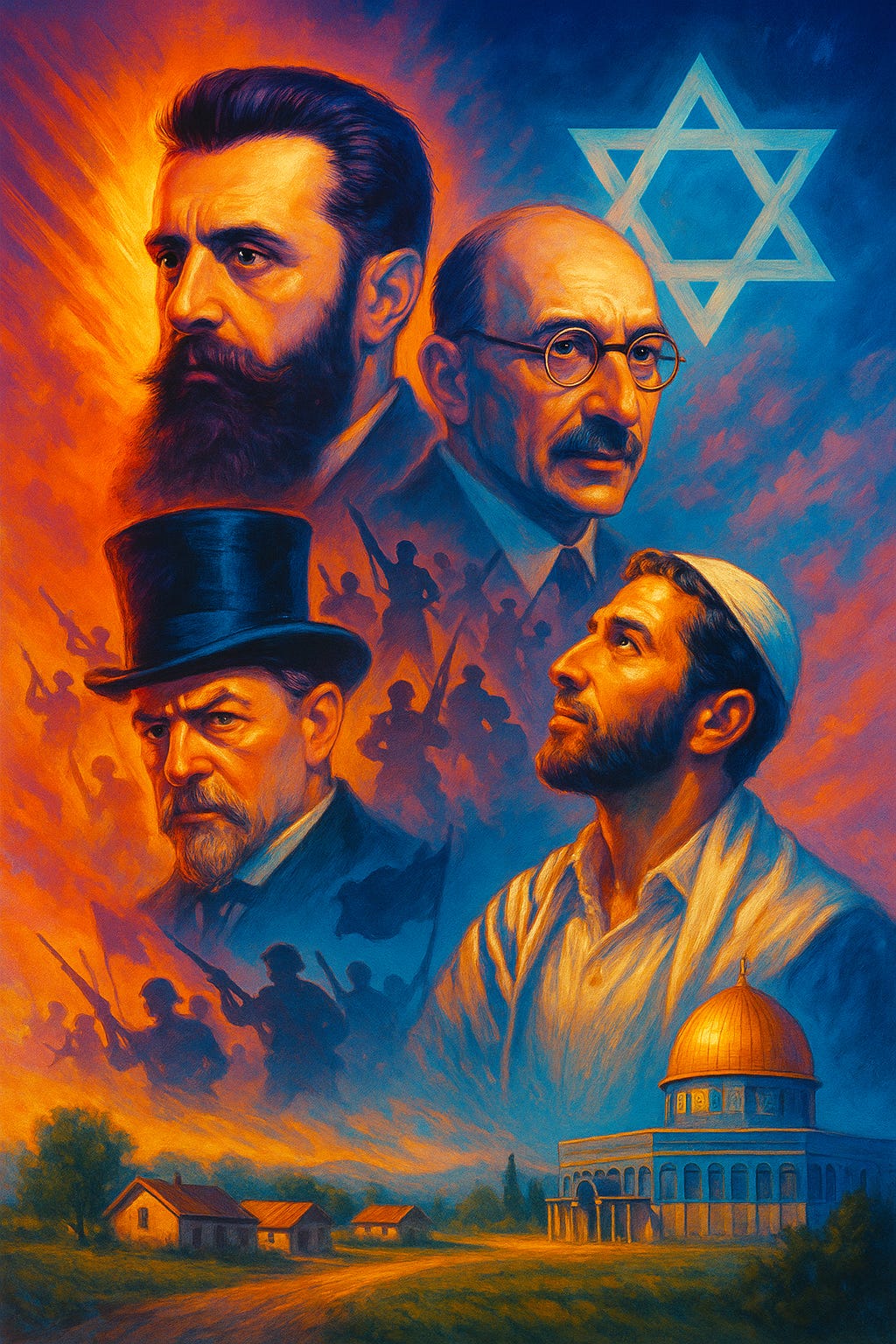

Zionism: A Homeland Born from Pain

The modern State of Israel was born from a centuries-long nightmare. Jewish people, scattered across continents since the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, had been persecuted, exiled, and massacred in nearly every land they lived in. For generations, they endured ghettos, pogroms, and expulsions—often in lands where they had no power and no protection.

The Zionist movement, emerging in the late 19th century, was more than a political campaign. It was a cry for refuge. It was a flame kept alive through centuries of darkness.

Ancient Persecution: From Rome to the Diaspora

Let’s rewind. In 70 CE, after a series of Jewish revolts, the Roman Empire crushed the Second Temple in Jerusalem—the heart of Jewish worship. The destruction wasn’t just military; it was symbolic. Rome sought to break Jewish identity. And it worked. Jews were exiled, scattered across the Mediterranean and into Europe. Their homeland was stripped from them. Their faith was suppressed.

In Roman cities, Jews were squeezed into narrow blocks of land. In Venice, their quarter was built over a foundry—getto in Italian. This is where we get the term “ghetto,” a grim reminder of forced isolation and cultural exile.

The Middle Ages: Isolation and Scapegoating

In medieval Europe, things didn’t get better—they got worse. During the Crusades, Jewish communities in German cities like Mainz and Worms were slaughtered en masse. Crusaders, fueled by religious zealotry, didn’t just march toward Jerusalem—they brought terror to their own backyards.

Jews were barred from land ownership, shut out of most trades, and confined to specific roles like moneylending—ironically fueling the same anti-Semitic tropes that would later be used against them. During the Black Death, Jews were blamed for poisoning wells.

Whole communities were burned alive.

Each massacre. Each exile. Each lie. They all carved fear and longing into the Jewish soul.

And they lit the fire under Zionism.

The Russian Empire: Pogroms and the Spark of Political Zionism

Fast forward to the 19th century. In the Russian Empire, anti-Semitism wasn’t just cultural—it was institutional. Jews were confined to the “Pale of Settlement,” stripped of civil rights, and regularly attacked in state-condoned pogroms.

In Kishinev in 1903, mobs murdered Jewish civilians, destroyed homes, and burned synagogues. It was a scene of chaos and blood—and it wasn’t an isolated case. Eastern Europe became a death trap.

Enter Theodor Herzl. An Austrian journalist who watched anti-Jewish riots unfold across Europe, Herzl believed the only way Jews would ever be safe was in a nation of their own.

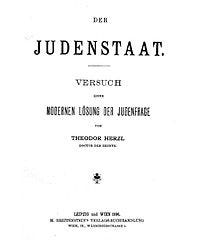

His 1896 pamphlet, "Der Judenstaat" (The Jewish State) outlined the need for a Jewish homeland to provide safety and autonomy for Jews facing persecution.

And so, political Zionism was born.

No longer just a spiritual longing, Zionism became a concrete goal: a sovereign Jewish state, in the land of Israel, where Jews could finally live free from persecution.

So, what led to the creation of Israel wasn’t prophecy—it was pain.

And the Israeli Palestine Conflict?

It’s not about ancient feuds—it’s the aftershock of a modern disaster, rooted in centuries of loss, and fueled by a fight for belonging.

The past is prologue—and now that you know how the story really began, let’s explore how it unfolded into one of the most divisive conflicts of the modern world.

Zionism in Action: From Herzl to British Politics

By the end of the 19th century, Zionism had evolved from a spiritual longing into a political mission. And while Theodor Herzl lit the match, it was men like Chaim Weizmann, Edmond de Rothschild, and Arthur Balfour who fanned the flame into something the world could no longer ignore.

This part of the story is where idealism meets realpolitik, where land meets legacy, and where Palestine, under British rule, became the staging ground for a future state.

After Herzl: Chaim Weizmann Takes the Reins

After Herzl’s death in 1904, the mantle of the Zionist movement passed to Chaim Weizmann, a Jewish chemist teaching at the University of Manchester. Unlike Herzl, Weizmann wasn’t just a writer or a dreamer—he was a savvy negotiator. He understood science, diplomacy, and how to charm the British elite over a dinner table or behind parliamentary doors.

His contributions to British war efforts during World War I gave him access to influential figures in the government. He used that access to push for a Jewish homeland—not as a favor, but as a strategic move the British could benefit from.

The Rothschild Legacy: Philanthropy Meets Politics

Baron Edmond de Rothschild and the Agricultural Settlements

While Weizmann worked the halls of power, Baron Edmond de Rothschild was quietly transforming the soil of Palestine itself.

Beginning in 1882, Rothschild bankrolled some of the first Jewish agricultural settlements, including Rishon Le-Zion, Zikhron Yaacov, and Maskereth Batya. His approach was practical: don’t just dream of a state—build one from the ground up.

He saw Herzl’s high-stakes political maneuvering as too reckless. In Rothschild’s view, true Zionism meant cultivating land, creating jobs, and establishing real infrastructure that could support future Jewish generations.

PICA, JNF, PLDC: The Infrastructure of a Homeland

Rothschild didn't just donate money—he built an ecosystem.

PICA (Palestine Jewish Colonization Association): By Rothschild’s death in 1934, it directly owned 123,500 acres (500,000 dunams) of land.

JNF (Jewish National Fund): By 1948, had secured roughly the same—another 123,500 acres.

PLDC (Palestine Land Development Company): Acted as a land-purchasing agent for Rothschild-backed groups.

Collectively, they had acquired land about the size of Los Angeles—not nearly enough to shelter all the Jews fleeing persecution in Europe, but a formidable start.

A Legacy Continued: James and Dorothy de Rothschild

After Edmond’s death, his son James de Rothschild took the reins of PICA, eventually transferring its holdings to Israeli national institutions in 1957. His wife, Dorothy de Rothschild, carried the legacy forward, establishing Yad Hanadiv, a foundation still active in Israeli public life.

Herzl vs. Rothschild: A Clash of Zionist Visions

Theodor Herzl envisioned a state born in embassies and summits. In his 1896 pamphlet, Der Judenstaat, he wrote:

“Palestine is our ever-memorable historic home... We should there form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism... The sanctuaries of Christendom would be safeguarded by assigning to them an extra-territorial status.”

Herzl offered the Ottoman Sultan financial incentives to hand over Palestine. Rothschild? He found that idea naïve at best—and risky at worst. Their rivalry was ideological:

Herzl believed salvation came through international recognition and treaties.

Rothschild believed it would come through self-reliance and sustainable farming communities.

This clash defined early Zionism. But the political game was heating up. The British Empire was cracking at the edges, and World War I would soon change the map forever.

British Empire Politics and the Zionist Opportunity

The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and Rise of the British Mandate

From 1517 to 1917, Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. But World War I flipped the region upside down. The British, through agents like T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), encouraged Arab tribes to rebel—promising them independence in a post-Ottoman world.

But those promises? They were double-crossed.

Sykes-Picot and the Carving of the Middle East

In secret, British diplomat Sir Mark Sykes and French counterpart François Georges-Picot created the infamous Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916.

They divvied up Ottoman lands into British and French zones of control—under the noble-sounding “Mandate System” and put these nations under the “tutelage of advanced nations.”

Yes. They said that.

Palestine? That went to Britain, first by military occupation in 1917, then formally under the League of Nations in 1922.

“No, no, we’re not going to rule you,” the British might’ve said. “We’re going to civilize you.”

But Britain had the guns. And the Arabs? They had 90% of the population—and very little say.

Arthur Balfour and the Zionist Connection

Arthur James Balfour was a former British Prime Minister and then the Foreign Secretary under David Lloyd George. He met Weizmann in 1906, and the two formed a cautious but effective alliance.

Balfour wasn't religious—some say he was a cynical elitist—but he was influenced by pro-Zionist Christians like Lloyd George, who believed in the prophetic importance of Jews returning to their homeland.

It was through his close relationship with Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild, cousin to Edmond and a key figure in British high society, that Balfour would make his mark on history.

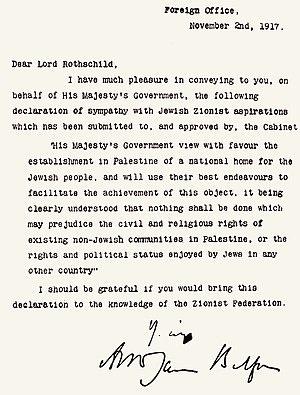

The Balfour Declaration (1917): Promise or Betrayal?

The Balfour Declaration was a 67-word letter addressed to Lord Rothschild that changed everything:

"His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people..."

It was vague. It was political. And it was explosive.

Why? Because Palestine already had a population—about 600,000 Arabs and just 60,000 Jews. Balfour knew this.

From latter remarks, it would appear that the sentiment of the Balfour Agreement was expressed more by David Lloyd George, than Balfour himself (though the document now famously bears his name). By all accounts, it would appear he was an atheist and a racist.

In 1919, he coldly admitted:

"In Palestine, we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country."

So just like that, Britain promised a homeland to one people—on land inhabited by another.

Conflict Builds: Arab Resistance and British Repression

Immigration and Unequal Development in Palestine

Following the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate, Jewish immigration skyrocketed. By 1936, Jews numbered around 400,000, with Arabs at 900,000. That’s a 2-to-1 ratio—still an Arab majority, but the growth was staggering.

Jewish settlers weren’t assimilating—they were building their own economy, schools, newspapers, and militia (the Haganah). To many Palestinians, it looked like a slow-motion invasion.

The Arab Revolt of 1936–1939: Palestine Erupts

The tension boiled over in 1936. Palestinians went on strike, protesting British favoritism toward Zionist goals and mass Jewish immigration.

The British Empire responded as it often did: with brutal repression. Historian Matthew Hughes documents:

“Prisoners jumped to their deaths from high windows... had their testicles tied with cord... were sodomised... hair was torn from their faces and heads… red hot skewers were used... there were mock executions.”

It was a massacre. Despite superior numbers, Palestinians lacked the organization and foreign funding that the Zionist movement had. They were outmatched—and outgunned.

The Peel Commission and the Two-State Proposal

In 1937, the British tried to throw water on the fire with the Peel Commission. It was a half-baked plan. The proposal? Split Palestine into two states.

Arabs: 900,000

Jews: 400,000

About 2 Arabs for every Jew.

You can also see just how large the immigration had become. However, immigration is perhaps not the best word. It implies an assimilation into the culture of the area you are immigrating to.

This was settlement.

So how was it divided?

Take a look:

Well, that doesn’t look too bad.

Except, to the Arabs, it was a slap in the face.

The plan gave Jews the most fertile land, and called for the displacement of 225,000 Arabs. The result? Arab outrage. Why should a minority population—arriving recently—receive land at the expense of a native majority?

The 1939 White Paper: A Temporary Shift

As the Arab Revolt dragged on, Britain’s patience wore thin. They issued the White Paper of 1939, a policy reversal that:

Rejected partition

Capped Jewish immigration at 75,000 over five years

Promised independence for Palestine within 10 years (shared by Arabs and Jews)

Palestinians were skeptical—justifiably. Zionists saw it as a betrayal. And for European Jews facing the rising threat of the Nazis, it was a death sentence.

The Stage Is Set

In response, Zionist militias turned their guns not just on Palestinians—but on the British. The Irgun, the Lehi, and even parts of the Haganah began sabotaging British infrastructure, bombing government buildings, and accelerating plans for a future state.

Then came World War II.

Then came the Holocaust.

Then came an international reckoning.

The fight for Palestine—and the birth of Israel—was no longer a regional issue.

It was about to become global.

Continued in Part Two.

Thank you for writing this.