Trump's Plan to Demolish the DOE: A Deep Dive (Part 1 of 3)

Explore the history of U.S. education before the DOE, the rise of teachers' unions, and Trump's plan to demolish the DOE. Learn how a new approach could reshape schools.

Part 1: The DOE’s Origins and Impact on U.S. Education

Education is one of those topics that sparks passionate debate. Everyone has an opinion, and many believe the system is broken. But where did the current system come from? And why hasn't it changed in decades despite overwhelming criticism? In this first part of our series, we’re diving into the history of education before the Department of Education (DOE), how the DOE came to be, and the key players and legislation that shaped the state of U.S. education today.

U.S. Education Before the Department of Education

Imagine a time when the federal government didn’t have its hands on the steering wheel of education. Before 1979, education was largely controlled at the state and local levels. Each state had its own system, its own standards, and its own way of teaching.

Was it perfect? Not at all.

But it allowed flexibility to cater to local needs.

However, it wasn’t all roses. There were huge disparities in the quality of education depending on where you lived. Students in wealthier areas often received a much better education than those in rural or low-income regions. Schools in poor districts struggled to keep up with those in affluent areas. You could say the system was a bit of a wild west, with some areas flourishing and others falling behind. During the 1970s, things were going south. Just look at the data compiled in Table 18 by the NCES.

Reading Proficiency:

9-year-olds: In 1975, around 73.6% of 9-year-olds reached the lowest proficiency level in reading, while only 14.6% reached the highest proficiency level.

13-year-olds: For 13-year-olds in the same period, 80.2% met the basic proficiency level, but just 3.8% demonstrated advanced proficiency.

17-year-olds: The reading performance for 17-year-olds saw about 52.7% achieving the basic proficiency standard, with 1.1% reaching the highest level, which reflects the academic struggles among older students in developing advanced literacy skills during this time.

Math Proficiency:

9-year-olds: Approximately 65.5% of 9-year-olds in 1975 achieved the basic proficiency level in mathematics, and only 5.9% were proficient at the highest level.

13-year-olds: Around 46.1% of 13-year-olds attained basic proficiency, but advanced proficiency was limited to just 4.2%.

17-year-olds: For 17-year-olds, only 19.2% reached the basic math proficiency, with a mere 0.6% reaching the highest level. This suggests significant challenges in higher-level math education at the high school level during the mid-1970s.

Science Proficiency:

9-year-olds: In science, 67.2% of 9-year-olds demonstrated basic proficiency, while 10.8% achieved the highest proficiency level.

13-year-olds: About 63.7% of 13-year-olds met the basic standard, with only 6.6% reaching the advanced level.

17-year-olds: Similar to mathematics, science proficiency for 17-year-olds lagged behind, with 42.2% reaching the basic level and only 1.6% reaching the highest proficiency.

Key Insights:

Declining Performance with Age: Across all subjects (reading, math, and science), younger students (9-year-olds) generally performed better at meeting proficiency standards than older students, particularly those at age 17. This suggests that as students progress through the education system, fewer are mastering advanced material.

Low Advanced Proficiency: In both math and science, advanced proficiency levels were extremely low for all age groups, especially for high school seniors (17-year-olds). For instance, only 0.6% of 17-year-olds were proficient at the highest math level in 1975.

So, it was clear there was a problem.

By 1990, there were clear improvements in basic proficiency, especially in math and reading, but the advanced proficiency levels remained stubbornly low, particularly for high school seniors. This suggests that while more students were achieving basic competency, the education system still struggled to foster deeper mastery of academic material.

So what could be done to improve this?

Very little.

In the 1970s, one thing was clear: the control and responsibility lay with the states. If a state wanted to innovate or change, it could do so without waiting for federal approval.

But, as we know, the larger the government entity, the slower the change.

In Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises, he writes:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

The Creation of the Department of Education: Key Players and Legislation

Everything changed in 1979. This is the year President Jimmy Carter pushed forward with his promise to create the Department of Education as a cabinet-level department. But why? The push for a federal education department was driven by several factors:

A desire for standardization across the country. The idea was to make sure students, no matter where they lived, would have access to similar educational opportunities.

Centralized federal funding to help underperforming or underfunded schools.

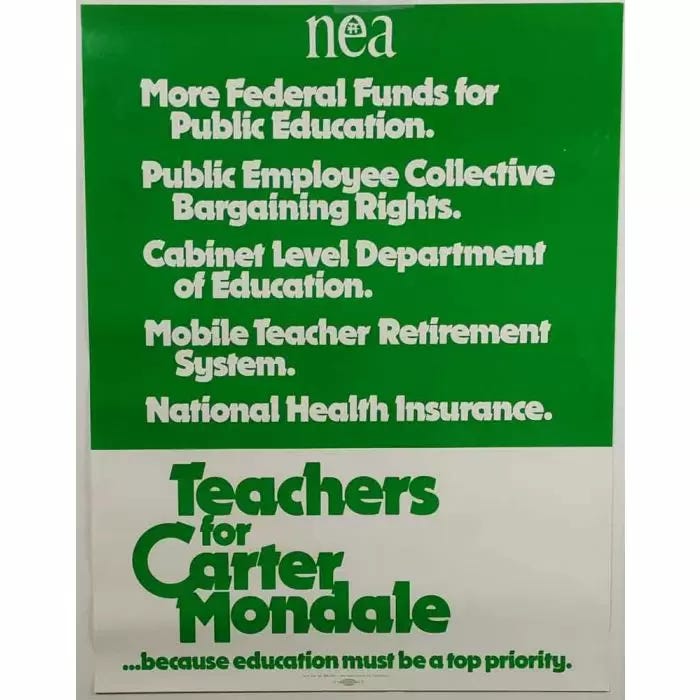

Lobbying from influential groups like the National Education Association (NEA), one of the largest teachers' unions.

With the DOE’s creation, the federal government now had a centralized role in education. The thought was: Why let states handle everything when we can create national standards and provide funding directly to schools?

Several key pieces of legislation followed:

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA)

The ESEA was originally passed in 1965 as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty. Its main goal was to address educational inequality by providing federal funding to schools, especially those serving low-income students. The act represented the first major federal intervention in education, designed to ensure that all children had access to quality education, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

Key Features of the Original ESEA:

Title I: The largest section of the ESEA, which allocated federal funds to schools with high percentages of students from low-income families.

Targeted Support: Funds were meant to help schools improve educational outcomes by addressing disparities in resources and providing additional support to disadvantaged students.

Civil Rights: The act also emphasized civil rights, ensuring that federal funds would not go to segregated schools or districts that did not comply with desegregation laws.

That doesn’t sound so bad.

However, after the creation of the Department of Education (DOE), the ESEA expanded significantly over the years. The original purpose of the ESEA was to promote equity in education, but as the DOE gained more oversight, states felt constrained by the growing federal mandates.

Even the teacher’s unions didn’t like it.

In the 1980s, these concerns grew. Teachers' unions expressed frustration with the bureaucracy created by federal requirements, which they argued shifted the focus from local educational needs to meeting federal benchmarks.

The monster grew. And, in 2001, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act had a rebrand when it was renewed.

It was called “No Child Left Behind.”

No Child Left Behind (NCLB)

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), signed into law in 2001 under President George W. Bush, faced significant controversy, particularly regarding issues of government overreach. NCLB sought to improve educational outcomes by holding schools accountable for student performance through rigorous testing and federal benchmarks.

Under the act, schools were required to meet Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) standards, which tied federal funding to student performance on standardized tests in reading and math. If schools failed to meet AYP, they faced escalating sanctions, such as restructuring or closure.

The act required annual testing in grades 3-8 and once in high school, with schools judged heavily on students' test scores.

This testing further narrowed the priorities of schools. There were no standardized tests for art, music, social studies, and the like. Reading, Science, and Mathematics. This become the focus of schools because that’s what their money was tied to.

NCLB set the goal that 100% of students should reach proficiency in reading and math by 2014—a target that was widely viewed as unrealistic.

Under NCLB, schools that failed to meet AYP for two consecutive years were subject to a series of increasingly severe interventions, including the possibility of staff changes, state takeover, or closure. This introduced a high-stakes, punitive system, which had no equivalent in the original ESEA

NCLB also introduced requirements for “highly qualified teachers,” mandating that all teachers in core academic subjects must meet specific criteria, another layer of regulation that was absent in ESEA.

While ESEA focused on funding and equity, NCLB added layers of testing, accountability, and punitive measures for schools that failed to meet performance targets, dramatically increasing the regulatory burden on states and districts.

And the government was just getting started.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

While ESSA built on NCLB’s goal of accountability and equity, it shifted the balance of control back to states and reduced the emphasis on punitive measures tied to standardized testing.

ESSA removed this specific federal mandate, returning teacher qualification standards to states and providing more support for professional development rather than imposing strict federal guidelines.

States were also encouraged to incorporate multiple measures of student and school success beyond just test scores, reducing the heavy emphasis on standardized testing that was central to NCLB.

For schools that did not meet Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), ESSA gave states and local districts the autonomy to choose interventions that best fit their context.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) was heralded as a significant improvement over No Child Left Behind (NCLB), but some critics have argued that it might function as a "Trojan horse" by subtly allowing states too much discretion while diminishing federal oversight, potentially leading to increased educational inequality.

By returning significant control to states, ESSA allows states to set their own accountability standards, goals, and interventions for struggling schools, which can vary widely.

Without stringent federal oversight, states or districts might prioritize bureaucratic expenses—like increasing administrative salaries or expanding non-essential services—over the direct needs of students, especially those in underserved communities.

With limited federal checks on how money is spent, there is a possibility that funds intended to improve student outcomes could instead be directed toward administrative costs or programs that don’t effectively address educational inequities. For example, spending could focus on increasing administrator pay or on expensive, non-impactful educational initiatives, leaving insufficient resources for critical needs like teacher support, classroom materials, or student services like tutoring or counseling.

The State of Education Today

Fast forward to today, and we have a bloated education system that is federally controlled in ways that were unimaginable before the DOE. Have things improved? That depends on who you ask.

On the one hand, standardization means that students in different states now follow more uniform curriculums, which is helpful for things like college admissions. Federal funding also helps struggling schools survive.

But on the other hand, and perhaps more important, achievement gaps remain a massive issue. Low-income districts still lag behind wealthier ones. The heavy emphasis on standardized testing has turned classrooms into test-prep centers, often stripping away creativity and localized solutions. Many argue that we’ve created a bureaucratic monster that’s more focused on checking boxes than on the individual needs of students.

Essentially, teachers are forced to “teaching to the test.” And the standardization did not accomplish what it was set up to do - improve education for low-income districts.

So, if it wasn’t working, why didn’t we fix it?

The Role of Teachers' Unions

Here’s where things get interesting. A major reason education hasn’t changed much is the influence of teachers' unions, specifically the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). These unions have historically backed the DOE and pushed for more federal involvement in education.

Why?

Because federal regulations and standards often benefit unionized teachers by securing job protections, benefits, and stable funding.

In September 1976, the NEA made its first presidential endorsement, with vice presidential candidate Walter Mondale addressing the group at its annual meeting. Mondale assured the NEA that a Carter administration would create a stand-alone, Cabinet-level Department of Education. Mondale, whose brother (William "Mort” Mondale) was a long-time NEA staffer, was a strong supporter of organized labor and increasing federal involvement in education. His selection as Carter’s running mate solidified the NEA’s backing of the campaign .

The NEA officially endorsed Carter, and its members turned out in large numbers at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. Although Carter generally opposed the expansion of federal agencies, he supported the idea of a Cabinet-level Department of Education to streamline grant programs and give education a stronger federal presence .

This endorsement paid off, as the NEA invested approximately $3 million in support of the Carter-Mondale campaign . However, progress was slow, prompting the NEA to launch a letter-writing campaign urging President Carter to fulfill his promise. By 1977, the union was actively collaborating with the administration to develop a legislative strategy for the creation of the Department of Education .

Who was Lester Mondale?

Lester Mondale, another brother of Carter’s Vice President Walter Mondale, was an influential figure in the American Humanist Movement. His involvement is reflected in the Humanist Manifestos he contributed to(both Manifesto I and Manifesto II), which provide insight into his values and philosophical outlook.

Here are quotes from Humanist Manifesto I and Humanist Manifesto II that address each of the key points about Lester Mondale's influence:

1. Commitment to Secularism and Rationalism

Humanist Manifesto I (1933):

"Religious humanists regard the universe as self-existing and not created."

"Humanism asserts that the nature of the universe depicted by modern science makes unacceptable any supernatural or cosmic guarantees of human values."

Humanist Manifesto II (1973):

"We find insufficient evidence for belief in the existence of a supernatural; it is either meaningless or irrelevant to the question of the survival and fulfillment of the human race."

"Promises of immortal salvation or fear of eternal damnation are both illusory and harmful."

2. Advocate for Progressive Social Change

Humanist Manifesto I (1933):

"The goal of humanism is a free and universal society in which people voluntarily and intelligently cooperate for the common good."

Humanist Manifesto II (1973):

"We affirm that moral values derive their source from human experience. Ethics is autonomous and situational, needing no theological or ideological sanction."

"We work for equal rights for all persons to the fullest possible extent."

"We affirm the equality of women and men."

3. Support for Global and Environmental Concerns

Humanist Manifesto II (1973):

"We deplore the division of humankind on nationalistic grounds. We have reached a turning point in human history where the best option is to transcend the limits of national sovereignty and to move toward the building of a world community."

"The future is, however, threatened by nuclear weapons, overpopulation, erosion of natural resources, and the growing disparity between rich and poor."

"A drastic reduction in the population of the globe is imperative."

"We must extend the principles of conservation to cover the use of the air, the waters, the soil, the forests, and other natural resources."

Does this sound like the soapbox of education we hear today?

While there is no recorded ties of either Mort Mondale or Walter Mondale agreeing with their brother’s beliefs, it would appear that the department they helped create and the education association embodied his views.

Make no mistake. The teachers unions have incredible power, often resisting reforms that would challenge their interests.

Want to change the way teachers are paid, introduce merit-based pay, or give local districts more control? Give parents a right to choose which school to send their kids to? Vouchers?

Chances are the unions will push back.

They wield immense political power, with a base that is only rivaled by the size of the teamsters, making sure that reforms that threaten their hold on the system don’t get very far.

Why Hasn’t Education Changed?

So, why haven’t we seen major changes in education despite the widespread agreement that something needs to be done? One reason is that the DOE, in partnership with the teachers' unions, has built an infrastructure that’s hard to break.

The DOE ensures that federal regulations stay in place, and the unions ensure that teachers benefit from those regulations. Together, they’ve created a system that resists reform, even when it’s clear the system isn’t working.

What’s next?

In the next part of this series, we’ll explore the role of the teachers' unions, how they’ve grown in power, and how they influence the education system today. It’s a story of money, politics, and the unintended consequences of federal control over local classrooms.