UKRAINE: The Psy-Op That Fooled The World

How Decades of Nationalist Narratives, Western Influence, and Hidden Agendas Shaped a Geopolitical Battleground

The Revolution of Dignity, also known as Euromaidan, was a pivotal moment in Ukraine’s history, occurring between November 2013 and February 2014. What began as mass protests against then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to suspend an association agreement with the European Union (favoring closer ties with Russia) escalated into a broader movement against corruption, authoritarianism, and Russian influence. The revolution culminated in Yanukovych’s ousting and the appointment of Oleksandr Turchynov as acting president in February 2014.

By June 2014, Petro Poroshenko, a Western-aligned oligarch, was elected president, followed in 2019 by Volodymyr Zelensky, a former comedian. While heralded as a democratic uprising, the Revolution of Dignity also set the stage for internal strife, growing nationalist sentiment, and the ongoing conflict with Russia.

However, beneath the surface, the Revolution of Dignity is tied to decades of ideological battles involving nationalist movements, Cold War-era covert operations like Operation Gladio, and modern geopolitical maneuvers. The resurgence of nationalist rhetoric, glorification of controversial figures such as Stepan Bandera, and the rise of far-right paramilitary groups like the Right Sector have all drawn accusations of ties to Nazi-fascist ideologies. These movements, coupled with Western influence, have shaped Ukraine’s turbulent political landscape.

This article examines the deep historical roots of the current conflict, tracing connections between Ukraine’s nationalist movements, World War II-era fascism, Cold War anti-Soviet strategies, and today’s geopolitical struggles. From the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) to the rise of the Right Sector and modern nationalist militias, we explore how Ukraine’s fight for sovereignty has been interwoven with controversial ideologies and global power dynamics.

Operation Gladio and Cold War Legacy

Operation Gladio was a clandestine "stay-behind" network established during the Cold War by NATO and the CIA to counter potential Soviet expansion into Western Europe. While its primary focus was on Western European nations such as Italy, Belgium, and West Germany, the broader framework of stay-behind operations had implications for Eastern Europe, including Ukraine, which was part of the Soviet Union at the time.

Ukraine itself was not a direct participant in NATO's Operation Gladio due to its status as a Soviet republic; however, its strategic location and large population made it an area of interest for Western intelligence agencies seeking to undermine Soviet influence.

During the Cold War, Western intelligence agencies, including the CIA, supported anti-Soviet nationalist movements within Ukraine, particularly through covert operations aimed at fostering resistance to Soviet control.

Groups such as the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) received funding and logistical support, though their activities were separate from the “formal” Gladio network. The Ukrainian resistance, like the formal Gladio network, was aimed to destabilize Soviet influence through covert means.

While Gladio's focus remained on NATO-aligned countries, the overarching strategy of countering Soviet dominance (aka communism) indirectly linked its principles to the activities in Ukraine during the Cold War.

Great thing with Operation Gladio - if you want something to be a threat, just label it as “communist.”

These efforts laid the groundwork for later Western engagement in Ukraine, particularly following the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Ukraine's geopolitical importance re-emerged in the context of NATO expansion and “Russian aggression.”

History of Nationalism

So, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), was established in 1929. Obviously, this was well before World War II. However, in the 1950s, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (the military wing of OUN) waged a guerrilla war against the Soviets. Then there was Right Sector and Svoboda, a modern Ukranian group which has been viewed by many as neo-nazi.

How do all these tie in though? Over 70 years?

By examining the chronological evolution of these connections, we can better understand how historical events and key players shaped today’s geopolitical narratives. Here’s how the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), Nazis, NATO, Operation Gladio, Right Sector, and Svoboda fit into this web of influence.

1930s–1940s: Birth of the OUN and UPA

Formation of the OUN (1929):

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was founded in 1929 as a nationalist movement aimed at achieving Ukrainian independence, particularly from Soviet and Polish control. Its ideology was deeply anti-communist and anti-Polish, shaped by the geopolitical pressures of the interwar period, where Ukraine was partitioned between Poland, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. While the movement's overarching goal was Ukrainian statehood, its internal factions diverged in their approaches, ideologies, and degrees of radicalism, leading to a split.

The split brought about two factions - The OUN-M (led by Andriy Melnyk) and the OUN-B (led by Stepan Bandera).

Stepan Bandera was a radical.

Stepan Bandera was a younger, charismatic, and radical nationalist who advocated for immediate and aggressive action to secure Ukrainian independence. His faction became synonymous with militant nationalism. They adopted a radical and often fascist-influenced ideology, embracing authoritarianism, militarism, and ethno-nationalism.

It emphasized the creation of a homogeneous Ukrainian state, free from external influences, and often targeted minorities such as Poles and Jews. It glorified violence as a means to achieve independence, advocating political assassinations and guerrilla warfare.

In case you need more proof of if the OUN-B was fascist, let’s look at the tell-tale signs in their platform and activities:

Authoritarianism: The OUN-B promoted a vision of a totalitarian Ukrainian state led by a "providnyk" (leader) with unquestioned authority, mirroring fascist leaders like Mussolini and Hitler.

Ethnic Purity: The Bandera faction's nationalism was explicitly ethno-centric, with the goal of a Ukraine free from Poles, Jews, Russians, and other minorities. This led to violent campaigns of ethnic cleansing, most infamously during the Volhynia massacres (1943–1944).

Cult of Violence: Violence was not just a tactic but a core part of the OUN-B's ideology, seen as a purifying and mobilizing force.

UPA and the Shift to Guerrilla Warfare (1942):

While the OUN-B was a political party, it needed a military wing.

Enter the UPA (Ukrayins'ka Povstans'ka Armiia, or, in English, Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

This military wing was initially tied to the Nazi movement, in hopes that they would support their vision of an independent Ukrainian state in exchange for their assistance during World War II. However, the Nazis viewed Ukraine primarily as a source of resources (such as grain) and manpower for the Reich, not as a partner in statehood.

So, as any good radical group would do, they turned on their ally after recognizing they would not help their agenda.

But not without poking the bear, first.

The OUN-B declared an independent Ukrainian state in Lviv on June 30, 1941, and declaring that their new, independent state would help the Nazis. Essentially, they were trying to force the Nazi’s support through public pressure.

They did not view it kindly.

The Nazis responded harshly. They arrested and imprisoned OUN leaders, including Stepan Bandera. This was not the first time Bandera was in prison though and, as fate would have it, he was released in September 1944 with the hope that he could fight the Soviet advance.

Bandera was shrewd though. Even though he was a prisoner, he negotiated with the Nazis to create the Ukrainian National Army and the Ukrainian National Committee in March 1945 in exchange for his help.

The Ukrainian National Committee (UNC) had Alfred Rosenberg as one of the initiators in creating the committee. And Rosenberg was a BAD DUDE.

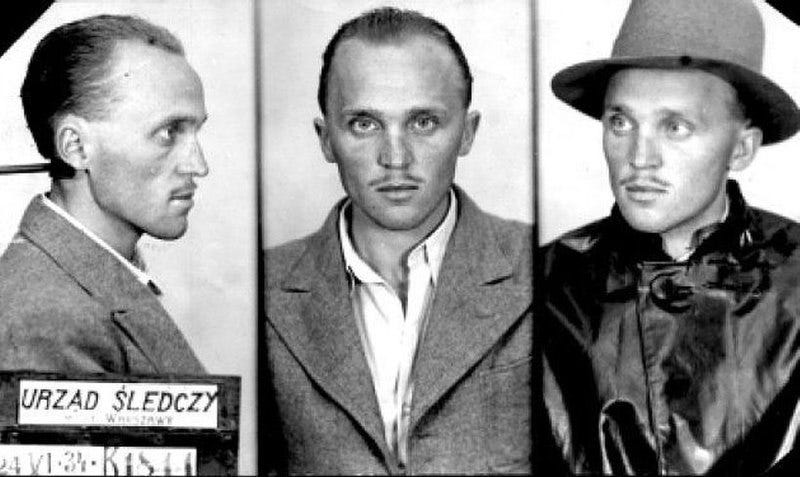

UNC’s founder - Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg was one of the most influential ideologues of Nazi Germany, playing a key role in shaping the regime's racist and anti-Semitic worldview. As a prominent member of the Nazi Party and one of Adolf Hitler's closest advisors on ideological matters, Rosenberg's ideas were instrumental in the development of Nazi policies that led to atrocities during the Holocaust and World War II.

He authored The Myth of the Twentieth Century (1930), which outlined a pseudo-historical and pseudo-scientific justification for Aryan racial superiority. (Basically the same influence that Darwin’s Origin of Species had on evolution. Not many people have read it, but most believe in it implicitly).

Rosenberg was also in charge of propaganda through the Nazi Party’s official newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter.

In summary, Rosenberg was not merely "bad" in the sense of being a supporter of the nazis—he was one of the primary architects of its ideology.

And this guy initiated this Ukrainian National Committee (UNC).

So, they kept fighting until the end. We know how that ended for the Nazis and their allies.

1945–1950s: Post-War Resistance and Western Involvement

After WWII, Eastern Europe fell under Soviet control, and the UPA continued its insurgency against Soviet authorities in western Ukraine (then part of the USSR). Western intelligence saw the UPA (particularly the OUN-B) as a potential ally in undermining Soviet influence and promoting anti-communist resistance.

At this point, Bandera relocated to Munich, Germany, where his faction became a central player in Ukrainian émigré politics. MI6 in particular reached out to Bandera and provided financial support, logistical aid, and training to his OUN-B operatives. So, Bandera became employed by Britain’s MI6.

But what Bandera really wanted was to live in the United States.

Allen Dulles (CIA) had denied this for some time, but finally, in October 1959, he granted Bandera a visa. Unfortunately for Bandera, the land of opportunity would not be his.

On October 15, 1959, 10 days after the visa recommendation, Bandera was allegedly assassinated in Munich by Bohdan Stashynsky, a KGB operative, using a cyanide spray gun. This assassination marked the culmination of Soviet efforts to neutralize him and disrupt Western-supported nationalist activities. However, it was known that Bandera was starting to fall out of favor with MI6.

So, was it really the soviets?

Regardless, BBandera was part of a much bigger operation.

The Enemy of My Enemy is My Friend

But the CIA and MI6 didn’t want to be seen interfering with international issues. So, the UNC often acted as a cover for covert operations, providing legitimacy to CIA or MI6 initiatives while masking their involvement.

The CIA, along with Britain’s MI6, initiated operations to support OUN/UPA factions.

Project AERODYNAMIC (CIA):

This project, started in 1953, focused on propaganda efforts, including the dissemination of anti-Soviet literature and infiltration of agents into Ukraine. According to the CIA documents, the purpose was stated as follows:

The purpose of Project AERODYNAMIC is to provide for the exploitation and expansion of the Anti-Soviet Ukrainian resistance movement for cold war and hot war purposes. Such groups as the Ukrainian Supreme Council of Liberation (UHVR), its military adjunct, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), all in the Ukraine, the Foreign Representation of the Supreme Council of Liberation (ZPUHVR) in Western Europe and the United States, and other Ukrainian organizations such as the Foreign Sections of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (ZchOUN), etc., will be utilized.

The project involved various covert activities, including:

Financial Assistance:

Funds to sustain émigré organizations like the Foreign Representation of the Supreme Council of Liberation (ZPUHVR) in Western Europe and the U.S.

Material Support:

Supplies, communication equipment, and weapons caches buried for use by Ukrainian resistance groups. (sounds a lot like Gladio)

Psychological Warfare:

Creation and distribution of propaganda (pamphlets, posters).

Support for the Suchasna Ukraina newspaper to unify émigré groups and amplify anti-Soviet messaging.

Agent Training and Infiltration:

Training Ukrainian agents in political and psychological warfare.

Deployment of agents into Soviet Ukraine for intelligence-gathering and sabotage.

Operational Support:

Establishment of safe houses and transit facilities in Ukraine.

Development of escape and evasion networks for agents.

Perhaps most chilling though is this excerpt:

Project Aerodynamic is the principal vehicle through which SB division conducts its operations against the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The main purpose of the project is to exploit contacts with Soviet Ukrainian citizens in order to encourage national and intellectual unrest in the Ukrainian SSR, thus encouraging cultural and intellectual freedom for Soviet citizens.

Groups like the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) and Prolog Research Corporation (a CIA-funded front) were actively involved in the propaganda and intelligence-gathering efforts.

The project also outlines creating cadre schools (essentially spy schools) with the overt goal to provide education for Ukrainian émigré youth, with a focus on citizenship and supplementary education for those who lacked prior opportunities.

Covertly, however, the goals were to train individuals for psychological warfare, political action, and guerrilla operations. It would also be used to identify and recruit operatives for clandestine missions inside the Ukrainian SSR.

So, did these schools ever happen?

Not in any documentations (why would they document where their spy schools were?). But one school is explicitly mentioned in the document:

The Free Ukrainian University in Munich is the most directly tied to the cadre school concept outlined in Project AERODYNAMIC. The university was known as a hub for Ukrainian émigré intellectuals and political activists during the Cold War and was to work parallel with the Lviv Ukranian University (important for later).

However, it is highly likely that other covert training facilities and programs in Germany, NATO-aligned centers, and émigré organizations like ZPUHVR also functioned as cadre schools or recruitment hubs.

These schools were critical to training operatives for psychological and guerrilla warfare while maintaining the appearance of legitimate émigré activities.

Other possible schools:

Oberammergau NATO School, Bavaria, Germany: Known for Cold War unconventional warfare training, this NATO facility likely hosted Ukrainian émigré recruits, providing instruction in guerrilla tactics, psychological warfare, and subversion.

Camp King, Oberursel, Germany: A U.S. Army Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) site, it served as a hub for intelligence and infiltration training, making it a probable location for preparing Ukrainian operatives for behind-the-Iron-Curtain missions.

Salzburg Training Sites, Salzburg, Austria: These facilities were staging areas for Eastern European émigrés participating in CIA infiltration missions, offering specialized training in sabotage, reconnaissance, and covert communications.

Displaced Persons Camp Riedenburg, Salzburg, Austria: A post-WWII refugee camp housing displaced Ukrainians, it served as a recruitment ground for clandestine training under Project AERODYNAMIC.

Wildflecken DP Camp, Bavaria, Germany: This displaced persons camp in Bavaria housed many Ukrainian émigrés, making it an ideal pool for recruitment and potential cadre training efforts.

Mittenwald Camp, Germany: Another displaced persons camp, it became a hotspot for Ukrainian nationalist activities and a likely recruitment and training site for covert operatives.

Oberursel NATO Psychological Warfare Division, Fontainebleau, France (later Casteau, Belgium): NATO’s Psychological Warfare Division collaborated with émigré groups like ZPUHVR, providing propaganda training and covert operational guidance for anti-Soviet activities.

Plast Ukrainian Scout Organization, Various Locations: This youth organization trained members in leadership and discipline, making it a valuable recruitment pool for further specialized training in covert operations.

Ukrainian Youth Association (CYM), Various Locations: Similar to Plast, CYM was an émigré group that cultivated nationalist ideals and organizational skills, providing recruits for CIA-backed training programs.

Operation PBCRUET Facilities, Western Germany: Tied to the AERODYNAMIC project, these facilities focused on propaganda and covert communication training for Ukrainian émigré operatives.

But the Soviets weren’t idiots.

Many agents sent into Ukraine by the CIA and MI6 were compromised. Soviet counterintelligence (NKVD, later KGB) infiltrated resistance networks and captured or killed infiltrators.

By the mid-1950s, the UPA's capacity for sustained resistance dwindled due to brutal Soviet counterinsurgency campaigns, including mass arrests, deportations, and executions.

But the operation was still successful.

Allen Dulles, in a letter, even wrote about Mykola Lebed, the chief of Bandera’s secret police. He wrote that Lebed was of “inestimable value to this Agency in its operations” and that he did “approve and recommend for your approval, the entrance of this subject into the United States for permanent residence.”

Yup.

The CIA authorized the immigration of a political assassin and perpetrator of the massacre of Poles.

So, in 1949, Lebed moved to the US and lived in New York City. There, he headed and was involved with the Prolog Research Center (a CIA front) for four decades. This center (later incorporated) was responsible for distributing propaganda through Ukraine. It also used its publication, Suchasnist, as a cover to gather intelligence.

The CIA shielded Lebed from prosecution for war crimes by preventing the USDOJ from learning about his wartime connections to the Nazis. He died in 1998.

Another important ally to western intelligence was Roman Shukhevych.

Shukhevych commanded the Nachtigall Battalion, which was a volunteer unit operating under the OUN. It was a subunit though, commanded by the German Abwehr special ops unit.

In other words, he was a Nazi (or at least Nazi collaborator). His military formation even served in German uniform.

Shukhevych was also the leader of the OUN from 1943 to 1950 and Supreme Commander of the Ukranian Insurgent Army (UPA). He used this position to initiate the mass murder of Poles and Jews throughout Ukraine.

Unfortunately for him though, the Ministry of State Security (MGB - think of it like a Soviet amalgam of the FBI, NSA, and CIA) found him in 1950. Shukhevych allegedly unalived himself while surrounded by 700 soldiers and his remains were burned and ashes scattered.

Since then, Shukhevych became a quasi-martyr for Ukranian independence.

Yes, the Nazi collaborator.

Statues have been erected. Movies made. Postage stamps and coins were minited in his honor. Even streets in Ukraine were named after him.

This preservation for Ukranian nationalism was kept alive by many Western countries, particularly the United States and Canada, who played key roles in preserving and amplifying these nationalist sentiments during the Soviet era.

Ukrainian diaspora communities in these nations, which grew after World War II due to the emigration of nationalists and anti-Soviet individuals, became vocal advocates for Ukrainian independence. These groups, such as the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America and the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, provided financial support, lobbied Western governments, and maintained a global awareness of Soviet repression in Ukraine.

Western radio broadcasts, such as those from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (funded by the CIA during the Cold War), also disseminated information about Ukrainian history, culture, and Soviet human rights abuses.

Additionally, the Helsinki Accords of 1975, which obligated the USSR to uphold human rights, gave Ukrainian dissidents a legal framework to demand greater freedoms. Western NGOs and political figures highlighted the plight of Ukrainian activists, creating international pressure on the Soviet Union. This blend of geopolitical pressure helped keep Ukrainian nationalist aspirations alive and prepared the ground for their resurgence as the USSR began to unravel.

1990s–2000s: Independence and Revival of Nationalist Symbols

After Ukraine gained independence in 1991, nationalist rhetoric experienced a resurgence. Symbols and figures from the OUN/UPA era were revived, particularly in western Ukraine, as icons of anti-Soviet resistance. This resurgence led to the formation of Social-National Party of Ukraine in 1991.

The SNPU was established by a group of young nationalists, including Yaroslav Andrushkiv, Andriy Parubiy, and others, with a focus on reviving Ukrainian nationalism in the newly independent Ukraine. The party adopted ultra-nationalist rhetoric and symbols directly tied to Stepan Bandera and the OUN-B. Just look at their emblem and you decide what it looks like:

The idealogy of the SNPU was based on OUN politician Yaroslav Stetsko’s Two revolutions. Stetsko was the leader of the OUN-B from 1941 until his death in 1986. Stetsko even wrote a letter in 1941 to Adolf Hitler expressing his gratitude and admiration for the German army.

Like Bandera, Stetsko was imprisoned by the Nazis when he was a part of the declaration of Ukrainian independence, but was also released when deemed useful against the Soviet Army. His and Bandera’s release was made possible by Otto Skorzeny.

After the war, Stetsko continued being political and became a board member of the World Anti-Communist League (which is a Gladio front). Stetsko was even received at the US Capitol by President Reagan and VP George H. W. Bush. They received him as "last premier of a free Ukrainian State.”

So, that’s some quick background on Stetsko. But what about his book from which the SNPU based their ideaology? The essence is contain in 1938 work “Without National Revolution there is no social one”:

The revolution will not end with the establishment of the Ukrainian state, but will go on to establish equal opportunities for all people to create and share material and spiritual values and in this respect the national revolution is also a social one.

That sounds like fascism to me.

Even, it’s founders, Andriy Parubiy and Oleh Tyahnybok, sound like a Gladio operatives or at least influenced by them.

They grew up in the Lviv region, which has a history of Nationalist sentiment. Both the OUN and UPA were very active there during and after World War II. In a 1962 CIA document, it was noted:

LVIV is nowadays much more Ukrainian than it was before WW II in spite of the numerous influx of Russians since 1945. The latter are called by Ukrainians "russki", "moskali", "katsapy.”

Nobody, not even Russians themselves, use the word "rosiyany". In LVIV there is also a great number of Ukrainians from Eastern Ukraine. A small group of Poles seems to be quite coherent and some of them, in particular elderly ones, still dream of "Polish Lviv". They are considered even by their compatriots as "maniacs".

The Russian element is regarded by local Ukrainians,in particular by intelligentsia, as inferior, "less cultured", "clumsy" foreigners. The new Ukrainian element in LVIV consists mostly of young people coming from the countryside. Some of them, for sheer opportunistic reasons, try to "emulate" Russians by using a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian.

Parubiy and Tyahnybok were also involved in nationalist student movements during their university years in Lviv. This university was also the birth place of Plast (a suspected CIA front mentioned earlier).

While there, Parubiy founded the youth organization "Spadshchyna" ("Heritage"), and Tyahnybok led the Lviv Student Fraternity. These organizations played roles in the formation of the SNPU, reflecting the nationalist fervor among young activists in the post-Soviet era.

Another group that popped up in the 90s was the “Trident named after Stepan Bandera” or simply “Trident.” This was founded through the OUN-B and had a reputation as being the most radical nationalist force in the 1990s-2000s. Dmiotry Yarosh, who would later lead the Right Sector organization, made his name in the Trident.

While organizations like the SNPU sought to bring nationalist ideologies into the political mainstream, groups such as the Trident and later Right Sector embodied a more militant approach.

Both streams, however, shared a common thread: the integration of historical narratives, including Bandera and Stetsko’s ideologies, into their vision for a modern Ukraine. This blend of political and paramilitary activism would later play a crucial role in Ukraine’s trajectory, particularly during the political upheavals of the 2000s and the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.

In this context, individuals like Andriy Parubiy, Oleh Tyahnybok, and Dmytro Yarosh represent the post-Soviet heirs to a nationalist tradition shaped by both domestic struggles and Cold War geopolitics. Their activities in the 1990s-2000s set the stage for the nationalist resurgence that would dominate parts of Ukraine’s political and cultural landscape in the 21st century.

2010s: Euromaidan and the Rise of Right Sector

The 2010s marked a critical juncture for Ukraine, with the Euromaidan protests (2013–2014) serving as a flashpoint for political upheaval and the resurgence of nationalist movements. The protests, sparked by then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s abrupt decision to reject an association agreement with the European Union in favor of closer ties with Russia, quickly evolved into a broader movement against corruption, authoritarianism, and Russian influence.

Among the prominent forces to emerge during this period was Right Sector, a coalition of far-right and nationalist organizations that became a significant player in Ukraine's political landscape.

The Formation and Role of Right Sector

Right Sector was officially formed in late 2013, during the early stages of the Euromaidan protests. It was a coalition of nationalist and far-right groups, including the Trident named after Stepan Bandera, Patriot of Ukraine, and other smaller organizations.

Dmytro Yarosh, a longtime nationalist activist and leader of the Trident, became the figurehead of the movement.

Right Sector positioned itself as a militant vanguard of the protests, organizing self-defense units and engaging in direct confrontations with riot police and government forces.

The group’s rhetoric and actions were heavily influenced by the legacy of the OUN-B and UPA, including armed resistance against both Soviet and Nazi forces during World War II. The red-and-black flag of the UPA became a common symbol among Right Sector members, underscoring their ideological roots in Bandera’s vision of Ukrainian nationalism.

Nationalist Ideology in Action

Right Sector framed its actions as a continuation of the fight for Ukrainian sovereignty, portraying Yanukovych’s government as a puppet of Moscow. This narrative resonated with many Ukrainians, particularly as the protests escalated into violent clashes and Yanukovych fled to Russia in February 2014.

It should be noted what some of Yanukovych’s policies and platforms were:

Centralization: Yanukovych’s administration faced real political instability in post-Soviet Ukraine, exacerbated by sharp ideological divides between the pro-European west and the pro-Russian east. There was also the rise of far-right nationalism. This threatened the unity of the state. Because of this, he sought to consolidate power. (something most people view negatively…considering a certain Austrian who also consolidated power.)

Yanukovych’s actions were thus seen as self-serving, aimed more at entrenching his power than addressing extremism.Ties to the Elites: The oligarchs who supported Yanukovych were primarily interested in keeping their economic interests growing. Their wealth depended on stable ties with both Russia and Europe (which the country was divided on). So, Yanukovych straddled the fence as best he could, to stay in their favor.

Unfortunately, this decision didn’t prove well.

Right Sector was the loud voice in the country. It was the BLM and Antifa rolled into one.

However, their extremism also sparked controversy. The group’s open embrace of figures like Bandera and its paramilitary structure echoed fascism and far-right extremism. These concerns were amplified by Russian propaganda, which used Right Sector as a symbol of the supposed "Nazi threat" in Ukraine to justify its annexation of Crimea and support for separatist movements in Eastern Ukraine.

But was Russia maybe right? *gasp*

Right Sector openly venerates Stepan Bandera and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Bandera faction (OUN-B), which collaborated with Nazi Germany during World War II and engaged in ethnic cleansing against Poles and Jews.

The group’s adoption of the red-and-black flag—a symbol historically tied to the UPA’s wartime atrocities—and its use of militant, paramilitary tactics strongly echo fascist movements of the past.

Right Sector's ideology prioritizes Ukrainian ethno-nationalism, often to the exclusion of minorities, aligning it ideologically with supremacist and ultranationalist movements.

Regardless, one thing was certain. There was unrest. And the tension in the country was about to snap.

From Protest to War

After Euromaidan, Right Sector transitioned from a protest movement to a paramilitary force involved in the Donbas War against Russian-backed separatists. The group’s military wing, the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps (DUK), became one of the first units to fight in Eastern Ukraine, operating independently of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Right Sector’s participation in the conflict further cemented its image as a defender of Ukrainian sovereignty, but it also deepened divisions within the country. The group’s nationalist ideology and tactics alienated some Ukrainians, particularly in the east and south, where pro-Russian sentiments were stronger.

In 2018, Parubiy (founder of SNPU, which became Slavoda) even said, during an interview on a show called Freedom of Speech on the ICTV channel, that the “greatest man who practiced direct democracy was Adolf Hitler in the 1930s.” And he didn’t stop there:

Parubiy said he had “scientifically studied” democracy and cautioned his audience “not to forget the contributions of the fuhrer to the development of democracy.”

He also added that it was “necessary to introduce direct democracy to Ukraine, with Hitler as its torchbearer.”

Political and Social Impact

In the aftermath of Euromaidan, Right Sector attempted to transition into mainstream politics but struggled to gain significant electoral support. In the 2014 parliamentary elections, the group won only a small percentage of the vote, reflecting the limited appeal of far-right nationalism in Ukraine as a whole.

Right Sector’s rise during the Euromaidan protests marked a turning point in Ukraine’s post-Soviet history. It highlighted the enduring power of nationalist narratives, the impact of historical memory, and the complexities of Ukraine’s geopolitical struggle between East and West.

The Aftermath of the Revolution of Dignity

After Victor Yanukovych was ousted, Petro Poroshenko was elected as Ukraine’s president in 2014. Poroshenko, a billionaire oligarch, had extensive business dealings in the West, raising suspicions about his allegiances. Leaked documents from the Panama Papers exposed Poroshenko’s offshore accounts, which further fueled speculation that his presidency was tied to Western corporate and intelligence networks. His pro-EU stance and efforts to integrate Ukraine into NATO mirrored longstanding U.S. and NATO goals to encircle Russia and neutralize its influence in Eastern Europe.

He also glorified Stepan Bandera and the OUN-B.

Western-backed NGOs, such as the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and USAID, were active in Ukraine during and after the revolution, funding civil society groups and media outlets that promoted anti-Russian narratives. Both of these groups have been connected to Operation Gladio.

Volodymyr Zelensky

Zelensky’s sudden ascent to power is, unusual, to say the least. He was a comedian with no prior political experience.

Zelensky’s campaign was heavily supported by Ihor Kolomoisky, an oligarch with ties to the West and significant influence in Ukraine’s media landscape. Kolomoisky’s role raises questions about whether Zelensky serves oligarchic and Western interests.

Zelensky’s pro-NATO rhetoric and insistence on Western military aid are also seen as aligning too conveniently with U.S. geopolitical goals. Zelensky has been vocal about Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO and the European Union, often framing this as essential for Ukraine’s security and modernization.

Ukraine has received significant financial and military aid (billions of dollars) from the U.S. and EU, especially since the escalation of the war with Russia in 2022.

Additionally, Zelensky has received public support from figures such as George Soros and leaders of the World Economic Forum (WEF), including Klaus Schwab. He also introduced controversial land reform laws allowing foreign ownership of Ukrainian farmland, a move supported by Western financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Under Zelensky’s administration, figures like Stepan Bandera and the OUN have continued to be honored in parts of Ukraine, especially in the west. Monuments, street renamings, and public commemorations of Bandera persist.

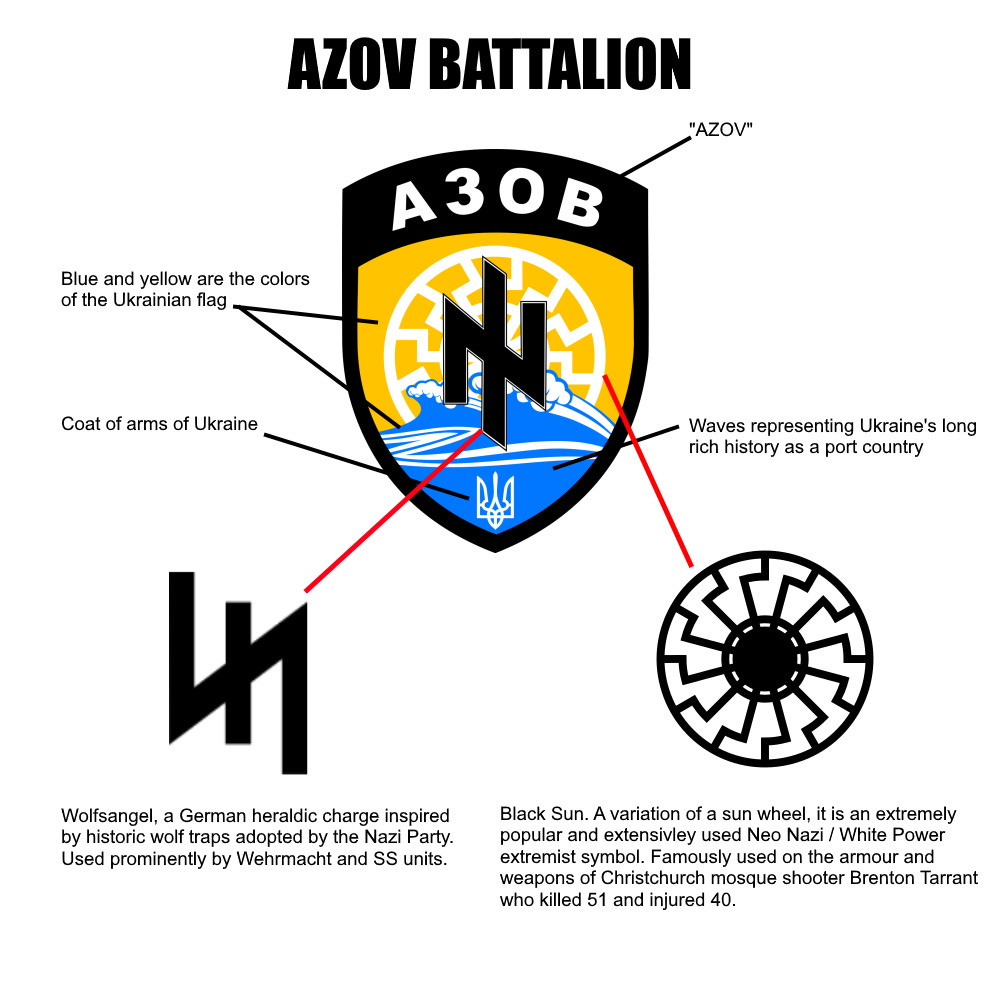

Zelensky has also cracked down on opposition. His government has banned pro-Russian political parties and media outlets, such as Opposition Platform - For Life, tied to figures like Viktor Medvedchuk. These actions have been applauded by nationalist groups like Right Sector and Svoboda. He has also integrated militias like the Azov Battalion (now the Azov Brigade) into Ukraine’s National Guard.

Interesting thing about the Azov Battalion: It was started by Andriy Biletsky, co-founder of the Social-National Assembly, an extremist group.

The SNA went on to help create an umbrella organization for other extremist groups like itself - this umbrella organization was the Right Sector.

Biletsky’s thesis at Kharkiv University focused on defending the activities of the UPA. He also headed the Kharkiv branch of Trident, was a member of the social-national party of Ukraine (later renamed Svoboda). In 2016, Biletsky even stated that “Azov” is ready to “take out this Council.”

The context isn’t any better:

"There is no point in talking with them [deputies].

If they will see us, if they will know that in the event of an attempt to hold such treasonous elections, we will take out this Council and AP.

And we will find new deputies... Today is just the beginning, but this is not the end of the action... We will fight, we will unite our ranks into a single, monolithic, ideological movement. Then over time, quickly, we will be able to change everything here.

This is a warning to them.

If it does not reach there, then the people have the right to defend themselves, to defend their territory and their lives by any means.

Sounds like a real moderate.

This is the ideology that was happily absorbed into the Ukraine national guard under Zelensky.

Summary Conclusion: The Current Situation in Ukraine and Its Ties to Nazi-Fascist Ideology

The current situation in Ukraine is deeply intertwined with the historical legacy of nationalist and fascist movements, which have been sustained, revived, and politically leveraged over the decades. These ties can be traced to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and its militant wing, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which collaborated with Nazi Germany during World War II and engaged in violent ethnic cleansing campaigns. The ideological foundation of these groups, rooted in ethnonationalism and “anti-communism”, was preserved during the Cold War through Western support as part of broader anti-Soviet strategies like Operation Gladio.

After Ukraine's independence in 1991, symbols, narratives, and figures like Stepan Bandera were revived as icons of resistance against Soviet oppression. This resurgence paved the way for the formation of far-right groups like the Social-National Party of Ukraine (SNPU) and later, militant organizations like the Right Sector and Azov Battalion, which openly glorified these historical figures and ideologies.

The Revolution of Dignity (Euromaidan) further amplified these elements, as ultra-nationalist factions became prominent players in protests against Viktor Yanukovych and, subsequently, in the conflict against Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas.

Post-Maidan leadership, including Petro Poroshenko and Volodymyr Zelensky, have continued to engage with these nationalist narratives. Poroshenko’s administration actively honored Bandera’s legacy, while Zelensky’s government incorporated far-right militias like the Azov Battalion into official structures such as the National Guard.

Zelensky's administration has also cracked down on pro-Russian political parties and media, actions applauded by nationalist factions like Right Sector and Svoboda.

These developments, combined with ongoing Western financial and military support and connections to figures like George Soros and institutions like the World Economic Forum, show that Ukraine’s leadership is both influenced by ultranationalist ideology and aligned with Western geopolitical goals.

Thus, the current conflict in Ukraine is a farce.

The west and the rest of the world has been sold on the propaganda that Russia is the big bad communist. But some may be surprised to learn a few things about Russia:

Putin was a KGB Agent. And not a communist. He eventually broke his KGB plead of allegiance.

Putin is not an atheist. He is Russian Orthodox. His mother was a Christian.

They denounce the Soviet Union.

Since Ukraine became a nation in 1991, Russia has had only one tense incident in 2003 over Tuzla Island. This was resolved diplomatically.

The annexation of Crimea was only carried out by Russia after 80% of Crimeans favored joining Russia.

This may be much different than what you have been told to believe. And what’s going on in Ukraine, and the web of its past, may also be much different.

Now, one thing must be made clear: The Ukrainian people are not the Ukrainian government.

If you’ve looked into Operation Gladio, you’ve likely found that America (or rather it’s government) is not so great. We’ve overthrown governments. Americans were lied to. History has been whitewashed. Criminals have been given asylum in the US, while Americans were treated as assets and chits.

But a corrupt government does not mean a corrupt people.

Ukrainians are wonderful people. They love their country. They want freedom and safety for their families, just like most people. They want a good life. So never confuse a criticism of a government as a criticism of a people.

So, the question of whether or not we should be involved with Ukraine boils down to this:

Do you trust Russia or Ukraine?

🤔. Umm some people are fooled. But they're getting there. The Azov Regiment. Zelensky’s Neo-Nazi guard has broken away from the old president and formed their own group. So that even if The government of Ukraine surrenders they're not going to stop fighting. The recruiting Americans in Canadians. You got to have Bitcoin 🙄. For advertising on Facebook and Instagram. I think we know how this ends. You get over there They get your Bitcoin and you disappear. 🤷♂️

Neither.