Universe 25: What a Mouse Apocalypse Says About Human Society

Discover the haunting lessons of Universe 25—the mouse utopia that spiraled into chaos. Could this bizarre experiment reflect where our society is headed?

Welcome to Mouse Heaven (Or Is It?)

Imagine a world where every need is met. Endless food. Free housing. No predators. No disease. Sounds like paradise, right?

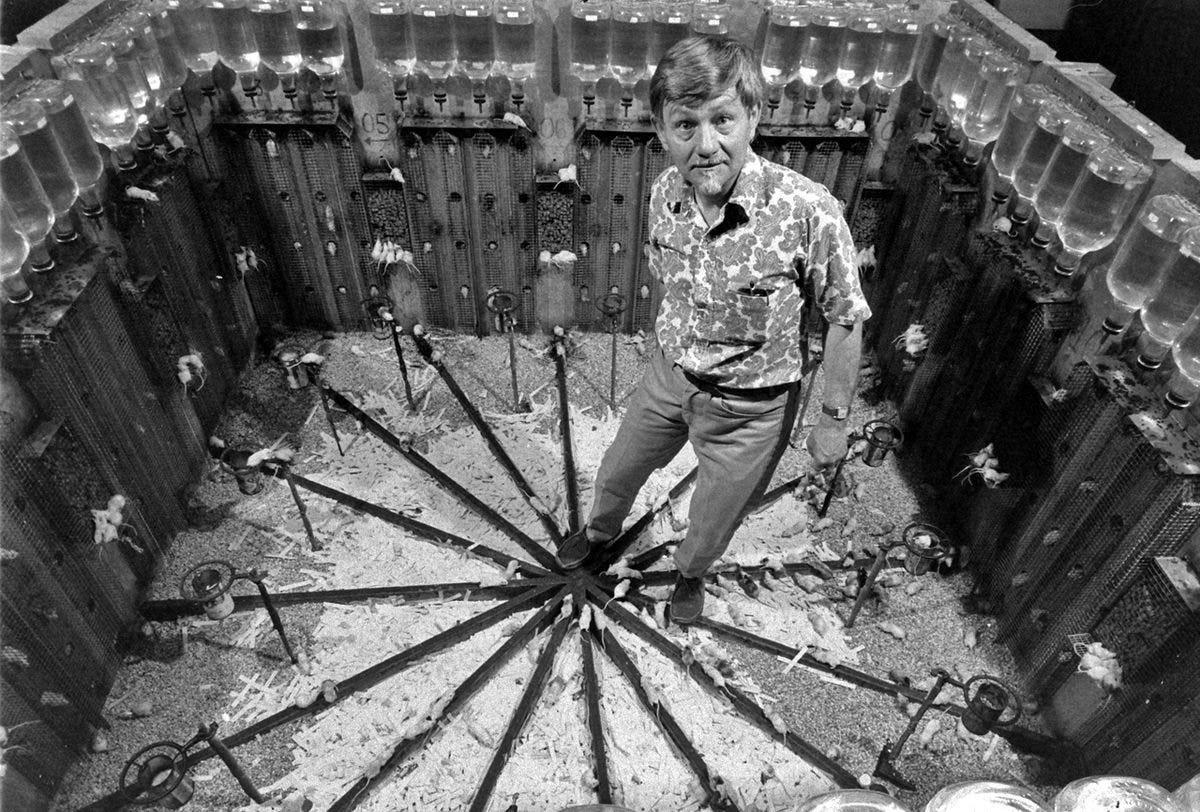

That’s exactly what researcher John B. Calhoun set out to build—not for humans, but for mice. He created Universe 25, a so-called utopia designed to explore what happens when a population lives without struggle. What unfolded, though, was anything but idyllic.

Instead of thriving, the mice descended into chaos: violence surged, parenting failed, social bonds crumbled, and eventually, the entire colony collapsed. All while surrounded by abundance.

So, what went wrong?

That’s the question that’s haunted scientists, psychologists, and even writers for decades. Universe 25 isn’t just a quirky mouse experiment tucked away in a dusty research journal. It’s a mirror—maybe even a warning—for us.

Because here’s the kicker:

What happened to the mice might not be about mice at all.

The Man Behind the Maze – Who Was John B. Calhoun?

Before we unravel the strange events of Universe 25, let’s meet the mind behind the madness: John B. Calhoun, an American ethologist with a deep curiosity about how overcrowding affects behavior—not just in animals, but in people too.

Born in 1917, Calhoun wasn’t your average scientist. He had a flair for the dramatic and a philosophical streak that made him more than just a data guy. He wanted to answer big, unsettling questions about what happens when a population grows too large, too fast—especially when all physical needs are met.

His early experiments in the late 1940s started small—literally.

Mice and rats, housed in confined spaces, began showing signs of stress, aggression, and social breakdown long before food or space actually ran out. These weren’t flukes. Calhoun repeated the experiments, tweaking conditions. The results were always weird, always dark, and always strangely familiar.

He coined the term "behavioral sink" to describe the collapse of normal social behavior due to overcrowding. It wasn’t just about space—it was about purpose, roles, and social order. Take those away, and even a paradise turns into a prison.

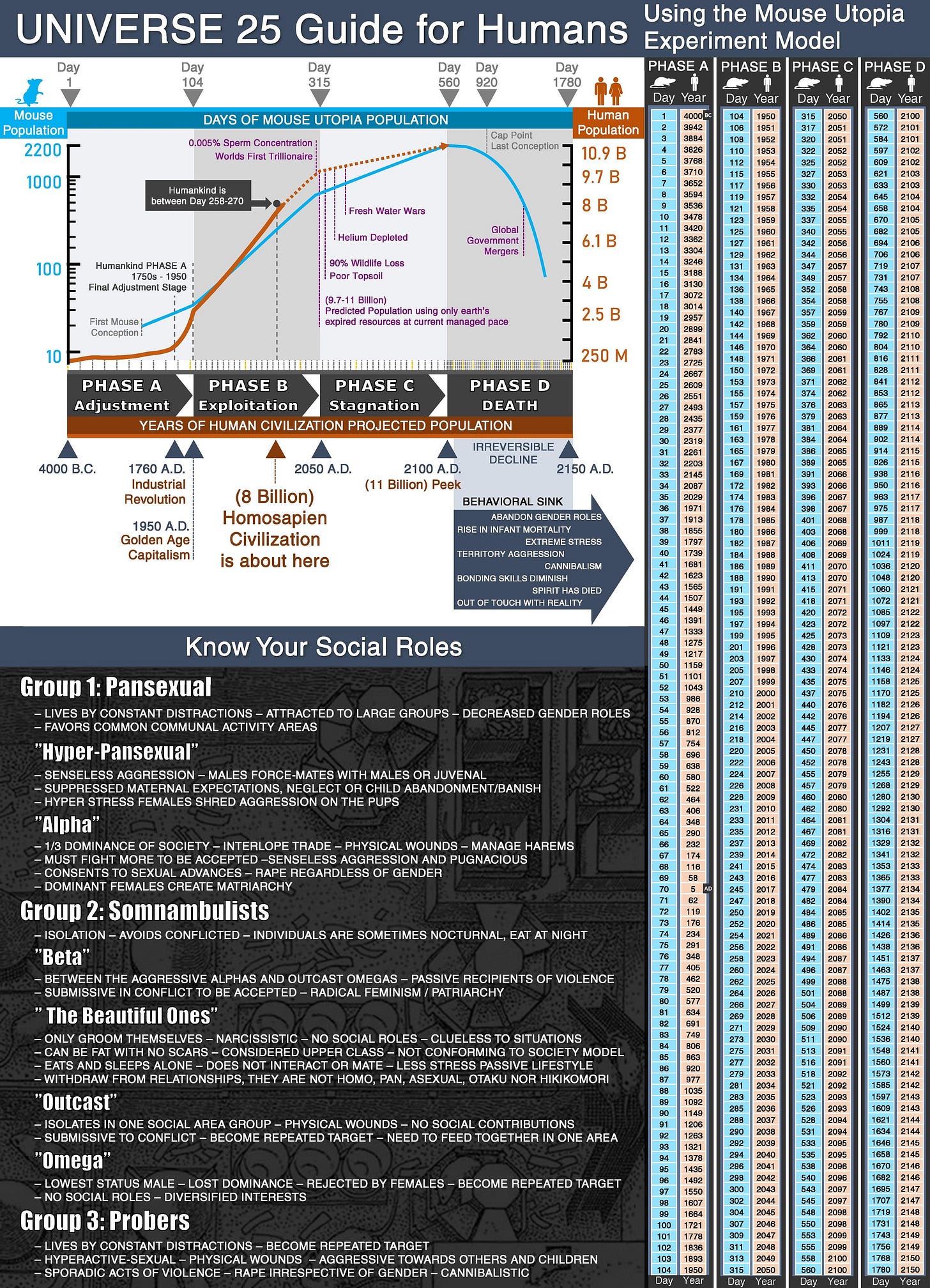

Before he created Universe 25, John B. Calhoun conducted 24 earlier experiments—each one a stepping stone in his quest to understand what happens when a society collapses under the weight of its own numbers. Run between the 1940s and 1960s, these trials—known collectively as Universes 1 through 24—tested rodents in environments free from predators, scarcity, or disease. The goal was always the same: to see how social creatures behave when survival is guaranteed, but space, roles, and identity start to erode.

While the core concept stayed consistent, several key aspects of these earlier universes differed from Universe 25:

Species: Early experiments mostly used Norway rats, while Universe 25 used mice, which tend to form more stable social groups under ideal conditions.

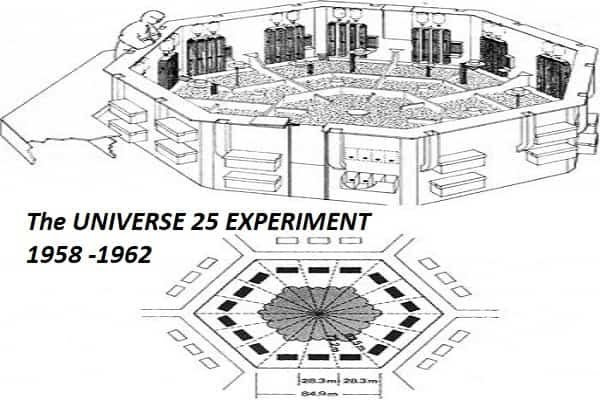

Enclosure Design: Initial setups were simpler, with basic boxes or compartments. Universe 25 was a multi-level, highly structured environment designed to mimic urban living.

Population Control: Some early trials capped population growth or used smaller groups. Universe 25 allowed the population to expand naturally, peaking at around 2,200 mice.

Experiment Duration: Many early universes lasted only a few months. Universe 25 ran for nearly two years, allowing researchers to observe multi-generational effects.

Focus of Observation: The earlier focus was on aggression and overcrowding, while Universe 25 examined the loss of social roles, parenting failure, and psychological decay.

By the time he launched Universe 25 in 1968, Calhoun had a hypothesis: that beyond a certain point, too much comfort could destroy a society from the inside out.

Spoiler alert: he wasn’t wrong.

So why mice? Because, as Calhoun saw it, their social structures aren’t so different from ours. They form hierarchies, nurture families, defend territory, and interact in surprisingly human-like ways. That’s what made his findings so compelling—and so terrifying.

Setting the Stage – Building a Mouse Paradise

Universe 25 didn’t start with chaos. It started with perfection.

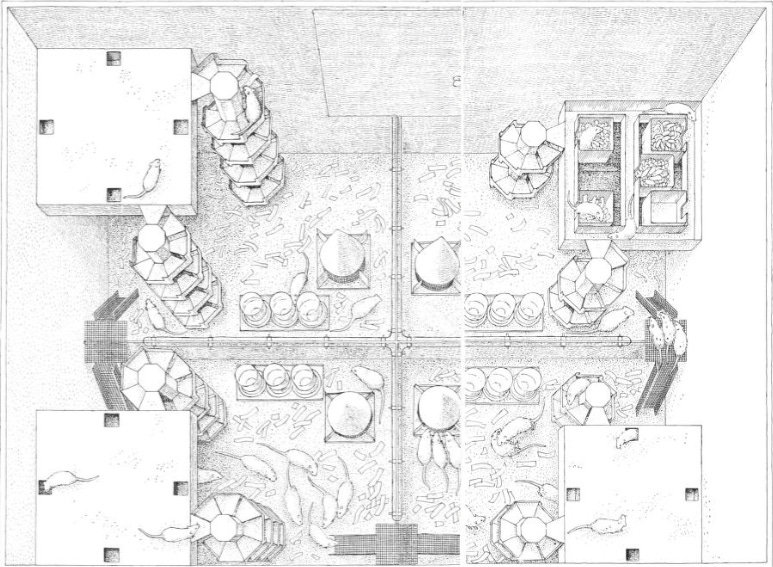

Calhoun and his team built a sleek, self-contained habitat about the size of a large closet. Think of it like a luxury condo complex for mice—complete with food dispensers, automatic water, nesting boxes, ramps, and plenty of clean space.

No predators.

No harsh weather.

No disease.

Just endless comfort and safety.

The setup could hold up to 3,840 mice, though Calhoun never expected to hit that number. What mattered was that every mouse had access to unlimited resources.

Nobody had to fight for survival.

No one needed to hunt or forage.

It was a world without struggle.

And here’s where it gets interesting.

At first, the mice behaved as you’d expect:

They formed small groups, built nests, mated, and raised pups.

The population doubled every couple of months.

Social order held.

Grooming was common.

Mothers nurtured their young.

Males defended territory.

Everything looked... normal.

In fact, the early days of Universe 25 were eerily idyllic. A rodent utopia.

But underneath that surface calm, something strange was brewing.

Because when everything is easy, something critical disappears: the need to adapt. The need to contribute. The need to struggle, yes—but also to belong.

As the population grew, space became tight—not physically at first, but psychologically. Social roles blurred. Conflict increased.

Some mice withdrew. Others turned aggressive.

And still others—the infamous “Beautiful Ones”—opted out entirely.

They stopped socializing.

Stopped mating.

Spent their days grooming themselves in isolation.

Sounding familiar?

Universe 25 was starting to crack.

At First, Things Were Great – The Golden Age of the Colony

For a while, everything in Universe 25 ran like a dream.

The mice flourished. Social structures formed. Nests filled with pups. Grooming rituals, play, and territorial behavior were all on display. You could almost hear the tiny squeaks of mouse contentment echoing through the chambers.

This was the Golden Age—a time of growth, stability, and relative peace.

The population doubled every 55 days. Mice paired off, raised their litters, and claimed their turf. Mothers were attentive. Males had roles. There was a kind of order in the chaos, and it worked.

For a while, anyway.

It all seemed like proof of concept: give creatures what they need, and they’ll thrive.

But here’s the catch—thriving isn’t just about survival. It’s about meaning.

As the number of mice ballooned past the hundreds, space wasn’t the problem—social breakdown was.

Territories overlapped.

Nesting spots grew crowded.

Fights broke out more often.

Mice no longer had clearly defined roles or places within the group. Parents became less protective. Dominant males got overwhelmed. And a lot of mice? They just gave up.

“Two other types of male emerged, both of which had resigned entirely from the struggle for dominance. They were, however, at exactly opposite poles as far as their levels of activity were concerned.

The first were completely passive and moved

through the community like somnambulists (sleepwalkers).

They ignored all the other rats of both sexes, and all the other rats ignored them. Even when the females were in estrus (heat), these passive animals made no advances to them.”

A handful became hyper-aggressive. Others retreated entirely. But most started showing signs of something deeper: a loss of purpose.

Think of it like this: imagine a town that keeps growing, where everyone has everything they need—but no jobs, no goals, no real connections. What happens next?

In Universe 25, what happened was the slow, steady unraveling of society.

The Golden Age faded. The dream began to rot.

And soon, the real nightmare began.

The Tipping Point – When Paradise Starts to Rot

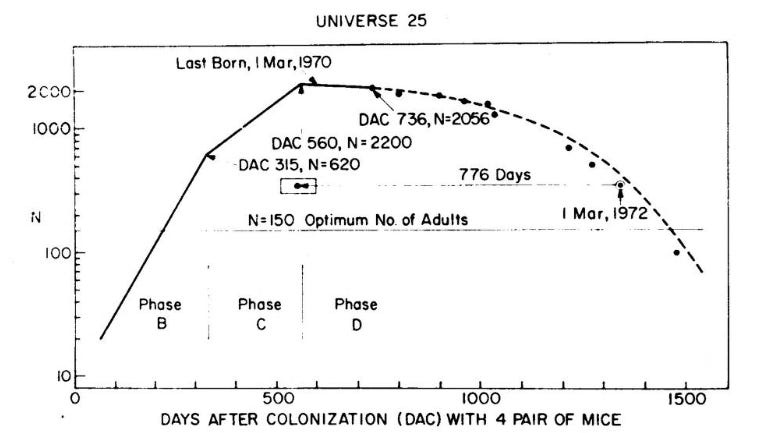

Every story of decline has a moment—subtle at first—when things begin to fracture. In Universe 25, that moment came just as the population passed 600.

What started as a utopia began to mutate. Social norms collapsed. Mothers abandoned their young, sometimes attacking or even killing them. Some pups were left to starve. Others were trampled in the chaos. Mating behavior declined. Instead of family units, mice clustered into unstable, anxious mobs.

And then came the violence.

Male mice, no longer able to defend territories, turned on each other. Random, brutal fights became common. The stronger ones dominated with cruel efficiency. The weaker ones withdrew, hunched and twitching, in corners of the enclosure. There was no leadership, no hierarchy—just disorder.

Meanwhile, something even stranger happened: a group of males began to opt out completely.

They stopped fighting. Stopped mating. Stopped doing anything, really.

These were the now-infamous “Beautiful Ones.”

Isolated, unscarred, and pristine, they groomed themselves constantly but had no interest in anything beyond their own reflection—yes, narcissistic mice.

They were physically perfect, but emotionally vacant.

Females fared no better.

Many lost interest in parenting. Some grew more aggressive than the males, attacking others at random.

Birth rates dropped sharply.

Infant mortality soared.

This was the turning point. The moment when population stopped meaning progress—and started meaning decay.

Despite having every physical need met, the mice were falling apart. Not because they couldn’t survive, but because they had nothing to live for.

No roles.

No struggle.

No connection.

Just endless days in a cage of abundance.

The stage was set for total collapse. And spoiler: it gets worse.

Total Collapse – Welcome to Mouse Hell

After the tipping point, Universe 25 didn’t just decline—it imploded.

The population peaked at 2,200 mice, far below the enclosure’s physical capacity. But by then, the problem wasn’t space—it was psychological decay. The social structure had disintegrated. Parenting had become rare. Reproduction nearly stopped.

And the few pups that were born? Most didn’t survive.

Violence was everywhere.

Some mice turned to cannibalism.

Others roamed without purpose, attacking randomly or simply wasting away in silence. The “Beautiful Ones” still preened obsessively, untouched by the bloodshed, but also untouched by meaning. They had become little more than decorative corpses.

No one mated. No one nurtured. No one built anything.

And then came the final generation.

This last cohort of mice—born into a world without structure, without parenting, without social learning—were raised by chaos.

They never saw nurturing behavior.

Never experienced boundaries, protection, or roles.

They were raised in apathy, and so, they became apathetic.

They didn’t know how to be mice.

They didn’t know how to be anything.

This generation refused to mate. Refused to interact. Refused to act. They simply… existed. Silent. Aimless. Waiting.

Eventually, the colony died off—not from starvation, disease, or predators, but from the absence of purpose. From the collapse of meaning.

Calhoun didn’t intervene. He let it play out, recording everything. And what he witnessed wasn’t just the death of a colony—it was the death of society.

A society that had everything… except the one thing it couldn’t live without: connection.

What Does This Say About Us? – The Human Parallel

Now here’s the part that makes Universe 25 hit a little too close to home.

Why does a decades-old mouse experiment keep popping up in conversations about cities, tech, loneliness, and the future of humanity? Because deep down, we know it’s not really about mice.

It’s about us.

And there’s other nuances in the study that are even more unsettling.

SIGNS OF THE TIMES

"Among the males the behavior disturbances ranged from sexual deviation to cannibalism and from frenetic overactivity to a pathological withdrawal from which individuals would emerge to eat, drink and move about only when other members of the community were asleep."

We see this mirrored in today's world in how people are either overstimulated and burning out or retreating into total isolation. Think about the rise in social anxiety, depression, and people who only interact online late at night. Some folks are always “on”—grinding, partying, constantly distracted—while others are completely checked out. Both extremes are signs that something’s off.

"Each of the experimental populations divided itself into several groups, in each of which the sex ratios were drastically modified. One group might consist of six or seven females and one male, whereas another would have 20 males and only 10 females."

This feels like the modern dating scene on steroids. Dating apps have created imbalances where a small number of people get most of the attention. Meanwhile, others feel completely left out. We’re also seeing more open relationships, hookup culture, and nontraditional group dynamics—just like those uneven rat groups.

"Individual rats would rarely eat except in the company of other rats."

Eating today has become a social ritual. Whether it’s filming mukbangs or grabbing brunch with friends, food isn’t just about survival anymore—it’s about connection, status, and content. It’s rare to find people who eat for survival (or health). We’re wired now to share the experience, whether in-person or online.

Food has become emotional.

"In the experiments in which the behavioral sink developed, infant mortality ran as high as 96 per cent among the most disoriented groups in the population. Even in the absence of the behavioral sink, in the second series of three experiments, infant mortality reached 80 per cent among the corresponding members of the experimental populations."

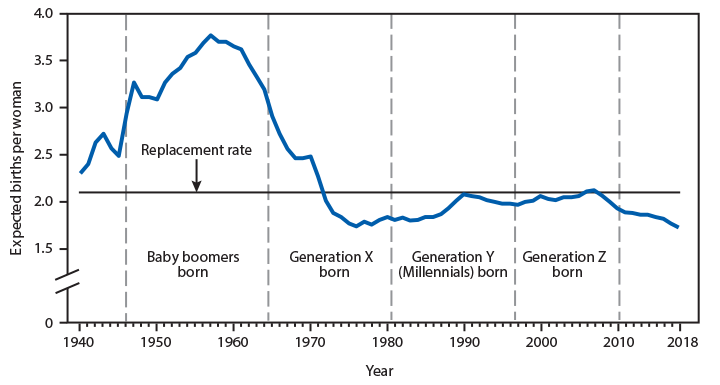

That’s shockingly reminescent to today’s declining birth rates. More people are choosing to stay child-free or are delaying parenthood because they feel the world is too chaotic or expensive to raise kids. Some even view having children as a burden, not a goal (One in Four US Women are expected to have an abortion in their lifetime).

"The middle-pen females similarly lost the ability to transport their litters from one place to another. They would move only part of their litters and would scatter them by depositing the infants in different places or simply dropping them on the floor of the pen...In the extreme disruption of their behavior during the later months of the population’s history they would build no nests at all but would bear their litters on the sawdust in the burrow box."

This hits hard when you think about parental burnout today. Many moms and dads are overwhelmed, under-supported, and just trying to keep their heads above water. We’re seeing more broken homes, neglect, and emotional detachment. It’s not that people don’t care—it’s that they’re stretched too thin to function the way they’re supposed to.

"With space for a colony of 12 adults in each pen— the size of the groups in which rats are normally found— this setup should have been able to support 48 rats comfortably. At the stabilized number of 80, an equal distribution of the animals would have found 20 adult rats in each pen. But the animals did not dispose themselves in this way."

People do the exact same thing. Even when there’s space in the suburbs or countryside, we pack ourselves into dense cities. We cluster with those who feel familiar. We stay where the jobs, culture, and our people are—even if it's too crowded and chaotic.

Community outweighs comfort.

"Perhaps the strangest of all the types that emerged among the males was the group I have called the probers...In addition to being hyperactive, the probers were both hypersexual and homosexual, and in time many of them became cannibalistic...These animals, which always lived in the middle pens, took no part at all in the status struggle. Nevertheless, they were the most active of all the males in the experimental populations, and they persisted in their activity in spite of attacks by the dominant animals.

They were always on the alert for estrous [read as ‘horny’] females... they would lie in wait for long periods at the tops of the ramps that gave on the brood pens and peer down into them...On these expeditions the probers often found dead young lying in the nests; as a result they tended to become cannibalistic in the later months of a population’s history."

It’s unsettling, but this reflects what we see in hypersexualized subcultures, voyeurism, and the rise of predatory behavior in digital spaces. Some people seem detached from moral norms, consumed by desire and obsession, even if it harms others. Even if those “desires” involve children. These behaviors thrive in overstimulated, broken environments—just like the rats.

"Below the dominant males both on the status scale and in their level of activity were the homosexuals— a group perhaps better described as pansexual...These animals apparently could not discriminate between appropriate and inappropriate sex partners. They made sexual advances to males, juveniles and females that were not in estrus."

Today, there’s a massive shift in how we view sexuality and gender. People are questioning everything—what attraction means, what gender means, what’s considered “appropriate.” Just look at how pedophiels are now being reclassified as “MAPs” (Minor Attracted Persons).

So, Is this Universe 25?

We’ve built digital worlds where we can curate, isolate, and self-groom—like the “Beautiful Ones.”

We scroll.

We binge.

We disconnect.

We surround ourselves with comfort, but often lack real community.

And while Calhoun never claimed Universe 25 was a perfect metaphor for human civilization, he did believe the experiment revealed something crucial: that social structures matter more than material ones. That purpose, connection, and contribution aren’t optional—they’re essential.

Without them, even paradise turns to ash.

So here’s the million-dollar question: Are we building our own Universe 25?

And if we are… what do we do before it collapses?

Are We Living in Universe 25?

In Calhoun’s Paper “Death Squared”, he finishes the study with an ominous ending:

As in the case of my study reported above, all members of the population will age and eventually die.

The species will die out.

For an animal so complex as man, there is no logical reason why a comparable sequence of events should not also lead to species extinction.

— Death Squared

Sure, we’re not mice. But we are social creatures—wired for connection, for struggle, for meaning. Strip those away, and no amount of comfort will save us.

Calhoun’s experiment didn’t just reveal the collapse of a colony. It showed us what happens when a society has all its physical needs met… and nothing else.

And that’s the unsettling part: the cracks he observed in Universe 25? We’re watching them form—in our cities, in our families, in our own psyches.

Maybe we’re not living in the end phase yet. But the conditions are familiar. Uncomfortably so.

We’re living in hard times—and understandably, we seek ease.

We want comfort.

Stability.

Our needs met.

There’s nothing wrong with that desire.

But somewhere along the way, that survival instinct became an obsession.

An expectation.

We stopped asking how to endure hardship—

And started demanding that it disappear.

And so, we turn—often without realizing it—

to the only force big enough to promise comfort without cost:

The government.

The institution that says: We’ll meet every need. Just hand over your agency.

“The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help.’”

— Ronald Reagan

The truth is: struggle is not the enemy. Discomfort is not a failure. They’re the pressure that forges character, identity, and connection.

Abundance without meaning is a slow death.

A full stomach isn’t the same as a full life.

We weren’t built for endless ease—we were built to build. To fight. To protect. To belong.

If we want to avoid the fate of Universe 25, we don’t need more government.

We need more soul.

We need to remember that true thriving doesn’t come from being taken care of—it comes from taking care. Of each other. Of our families. Of our purpose.

Because the moment we stop struggling for something greater than ourselves...

Is the moment we start grooming ourselves in the dark.

Waiting for the end.

FAQs – Quick Answers to Big Questions

Q: Was Universe 25 a failure?

Not exactly. While the outcome was grim, the experiment succeeded in revealing how social and psychological needs are just as vital as physical ones. Calhoun didn’t set out to create a failure—he set out to observe what happens when a society has everything except meaning. And that’s exactly what he documented.

Q: Could this happen to humans the same way it did to mice?

Not in the exact same way—humans are far more complex. But the core idea? That too much comfort without connection or purpose can lead to societal breakdown? That’s very real. Universe 25 isn’t a prophecy—it’s a metaphor. A mirror we’d be wise to glance into.

Q: What were the “Beautiful Ones,” really?

The “Beautiful Ones” were male mice that withdrew from society. They didn’t fight, didn’t mate, didn’t parent. They simply groomed themselves and lived in isolation. Physically perfect, but socially and emotionally vacant, they’ve become a symbol of disconnection in the age of abundance.

Q: Could the experiment be repeated today?

Technically, yes—but ethically, it would face heavy scrutiny. Plus, we already have mountains of behavioral data from digital spaces, urban studies, and mental health trends that reflect many of Calhoun’s findings. We may not need another mouse utopia to see that how we structure society deeply matters.