The Blueprint Pt 1/3: The CIA’s Global Coup Machine (1950s–70s)

Learn how the CIA overthrew governments from Guatemala to Greece, using propaganda, coups, and economic sabotage to shape the world to their goals.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the CIA orchestrated a series of covert operations that toppled democratically elected leaders and installed authoritarian regimes across Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

These actions were often justified under the guise of containing communism but frequently served to protect U.S. economic interests and geopolitical influence.

Actually, scratch that.

They ALWAYS served US interests.

Guatemala (1954)

President Jacobo Árbenz wanted to give unused land to peasants.

Seems like a good-guy thing to do.

Problem was, that land belonged to United Fruit Company—a U.S. corporate darling (which also was a front for the CIA).

The CIA responded with Operation PBSUCCESS: fake radio stations, propaganda drops, and a mercenary invasion force from Honduras.

Árbenz fled.

A dictatorship moved in.

United Fruit kept its grip.

The people? Not so lucky.

Paraguay (1954)

General Alfredo Stroessner didn’t come to power with fanfare.

Just quiet approval from the U.S.

Backed by anti-communist funding and Cold War paranoia, he seized control and ruled for 35 years.

Torture, censorship, disappearances—all tolerated in exchange for loyalty.

Paraguay went on to have more coups in 1989, 1996, and 2000.

DR Congo (1961)

Newly independent Congo was rich in uranium, cobalt, copper, and other minerals—and Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was looking East.

So the West looked the other way as he was captured, beaten, and executed by Belgian-backed forces.

A CIA favorite, Mobutu Sese Seko, took over, ruled for decades, and opened up Congo’s resources to the West. He allowed the CIA to use Zaire (he renamed the country) as a regional intelligence hub.

He was rewarded—lavishly.

Billions of dollars in military and economic aid from the US flowed to Mobutu.

Peru (1963)

Talk of land reform and redistribution was in the air.

The U.S. wasn’t having it.

“It was pointed out to the President that the contrast between the $20 million apparently available for new submarines and the $1.3 million set aside in the budget for the cost of land reform was scandalous and would be likely to evoke embarrassing questions in connection with our aid program for Peru.”

— Memorandum of Conversation, 1963.

“In the past, Peruvian Governments have been unwilling to make the sacrifices or to risk the political liabilities of programs aimed at bringing about fundamental social and economic change…This situation augurs a breakup of the existing structure of the Peruvian society and economy.”

— National Intelligence Estimate, “Political Prospects in Peru”

Conservative candidates were quietly bankrolled, fear campaigns spread through the press, and military leaders were whispered promises of aid.

Fernando Belaúnde, supported by the Christian Democrat Party (sounds a lot like Italy in 1947), won with 39% of the vote.

This, however, was after he lost in 1962. Surprise—the military junta staged a coup d'état after the loss and, a year later, Belaúnde was in.

Sounds like Belaúnde got benched during the big game, so Daddy USA talked to the coach and slipped him a

The reformers lost momentum.

The U.S. kept Peru in its economic orbit.

Greece (1967)

The left was gaining ground. Elections were looming.

So the military stepped in, backed by CIA guidance. (and $1M annually)

And the British too.

The Colonels’ Coup suspended democracy overnight.

Dissidents were jailed.

Torture chambers reopened.

But Greece joined NATO, and their southern flank was safe.

It also extended NATO’s reach to border Pakistan.

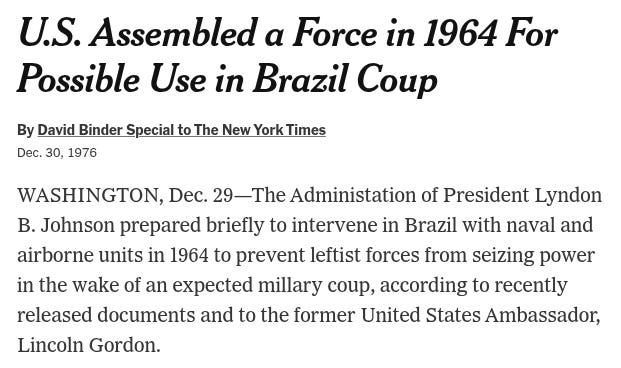

Brazil (1964)

President João Goulart wasn’t a Marxist—but he was nationalizing too much for Washington’s comfort.

So, the U.S. staged naval "exercises" off the coast while Brazilian generals rolled tanks into Rio.

A junta took power. Again.

The CIA smiled.

Brazil remained open for business—for decades. They severed diplomatic relations with Cuba and China, supported U.S. actions in the Dominican Republic, and advocated for the creation of an Inter-American Peace Force to counter “leftist movements” in the region .

Mission accomplished.

Dominican Republic (1960s)

Juan Bosch’s mild reforms and talk of land redistribution spooked U.S. planners.

And, of course, communism.

Except, once again, he wasn’t really a communist.

But no matter. He was committed to constitutional liberalism:

He protected civil liberties

Allowed opposition parties, even Marxist ones

Opposed censorship and arbitrary arrests

Resisted handing over power to the military

And that was bad enough.

When loyalists tried to reinstate him after a coup, the U.S. sent in over 22,000 troops, citing fears of “another Cuba.” This was Operation Power Pack.

A new government was installed (Joaquín Balaguer).

Bosch was out.

Order, and foreign investment, returned.

Under Balaguer, U.S. investments in the Dominican Republic nearly quadrupled—from $155 million in 1965 to $600 million by 1977. American and allied companies gained access to mining, sugar, finance, and tourism, with firms like Falconbridge, Rosario Dominicana, Shell, Gulf & Western, and Philip Morris reaping the rewards.

This is why Washington backed Balaguer—not because he was democratic, but because he was profitable.

Turns out, sovereignty is conditional—and democracy only matters if Washington approves the winner.

Laos (1960s–1970s)

After France's defeat in Indochina, Laos was labeled “neutral” by the Geneva Accords.

But neutral wasn’t good enough for the US.

By 1958, the Pathet Lao—left-leaning, nationalist, and gaining traction—started winning elections. That set off alarms.

Then came 1960. Captain Kong Le, a paratrooper with populist leanings, launched a coup to restore true neutrality—he opposed U.S. and Soviet meddling alike.

Whoops.

The CIA immediately backed General Phoumi Nosavan, a reliable anti-communist. With U.S. money, weapons, and “advisors,” Phoumi’s forces ousted Kong Le by December 1960.

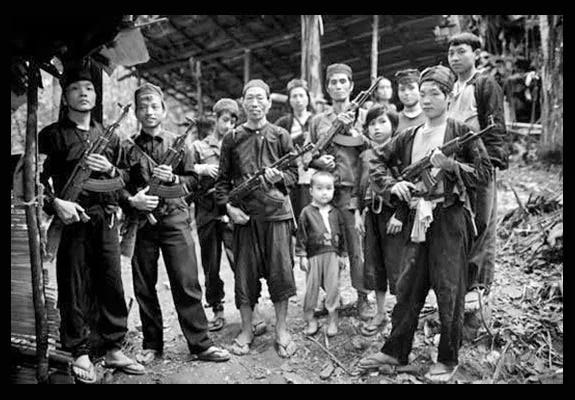

Once Phoumi and other U.S.-aligned leaders were in power, Laos became a proxy battlefield. The CIA trained over 30,000 Hmong fighters, led by General Vang Pao.

“The largest paramilitary operations ever undertaken by the CIA.”

Using tribal fighters and air drops, Langley ran America’s largest covert war.

But it wasn’t a real war. Not even the Vietnam war.

It was a drug war.

“Opium was the economic cement binding the parties [the Hmong and Americans] together much more closely than anti-communism could.”

— Ramparts Magazine, 1971

Using Air America—CIA-run planes masked as humanitarian aid flights—they ferried opium harvested in the mountains by Hmong allies straight into the Golden Triangle’s black market.

In exchange, the CIA armed and funded militias to fight “communists”, all while flooding Southeast Asia (and eventually American cities) with heroin.

This wasn’t just a side effect.

It was part of the Gladio playbook: finance covert war through covert trafficking—and leave no paper trail.

Vietnam (1963 Coup)

South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem had become a liability. Initially, he had been handpicked and backed by the U.S. after 1954 to lead South Vietnam.

But now, he wouldn’t follow orders…I mean advice. He was running his country like an autocracy.

In 1963, there was the emphasis “Buddhist Crisis” where Diem’s grovernment brutally cracked down on Buddhist protests, including a massacre in Hue and the infamous self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức.

So, the US needed someone who would play ball.

Diem wouldn’t.

He stonewalled American “advisors,” refused to expand the war on Washington’s terms, and worst of all—he was making peace overtures.

That was a problem.

Back in Washington, JFK had already signed off on a phased withdrawal (this was in October 1963). The plan would pull most U.S. troops out of Vietnam by the end of 1964, and nearly all by 1965.

In October 1963, JFK had even signed off on a plan to withdraw U.S. forces from Vietnam entirely. Most troops out by ’64. Virtually all gone by ’65.

But peace wasn’t profitable. And Diem wasn’t obedient.

So the narrative changed.

American media turned Diem into a cartoon villain—a tyrant oppressing peaceful Buddhists. News cycles hammered home the image of a Catholic dictator brutalizing monks.

But it wasn’t the whole truth. (Surprise, Surprise)

Diem had actually supported Buddhism for years. He sponsored temples—including Xá Lợi Pagoda in 1956—and had good relations with Buddhist leaders until the political climate shifted in 1963.

That’s when the Buddhist movement—led by figures like Thích Trí Quang—became a direct political threat, not a religious one.

It wasn’t oppression.

It was a power struggle, between two competing visions for Vietnam.

The Buddhists didn’t want reform. They wanted regime change. Trí Quang made it clear: they wouldn’t stop until Diem was removed, even calling for “suicide volunteers” to bring down the government.

Diem responded like he had before—with force.

The Xá Lợi Pagoda raids broke the movement. And, crucially, they were backed by South Vietnam’s military brass, who had helped plan the crackdowns.

But Washington’s disapproval changed the equation.

Diem had lost the narrative abroad.

The press turned.

Support evaporated.

And soon, the very generals who once backed him were answering to a new voice—the one from Langley.

So, the CIA coordinated a military coup, and Diem was assassinated.

By the CIA. Allegedly.

Unfortunately for the CIA, the assassination was not quiet enough.

One version said they swallowed poison.

Another claimed they were shot trying to wrestle a grenade.

The final account?

Machine-gunned in the back of an armored car after surrendering.

Everyone pointed to General Dương Văn Minh, the coup’s front man.

But no one doubted who lit the fuse.

Even JFK looked haunted.

After hearing the news, he left the room mid-briefing—ashen-faced. Later, he called the hit “particularly abhorrent,” blaming himself for approving Cable 243—the greenlight for regime change.

Three weeks later, JFK was dead.

And the war was back on track.

Washington reinstated the Commercial Import Program—South Vietnam’s main U.S. aid pipeline, frozen during Diem’s final days. The State Department made nice with the new generals. The CIA embedded deeper. And within months, boots were on the ground, bombers in the sky, and the Gladio doctrine upgraded from proxy warfare to full-blown military occupation.

Diem had tried to keep Vietnam from becoming a chess piece.

Now, the board was cleared.

The game could begin.

Bolivia (1971)

Leftist officers, under General Torres, held power. Turns out, they had an “anti-imperialist” stance.

Torres pushed back against Washington. Ambassador Ernest Siracusa—same one who helped take down Arbenz in Guatemala—demanded a policy shift.

The threat?

Total financial block.

The World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank followed suit.

No loans. No development.

In D.C., plans moved quietly.

Nixon and Kissinger discussed a coup.

The 40 Committee (later called the Special Intelligence Office) approved covert funds for the opposition.

August 1971—General Hugo Banzer moved.

Armed. Organized.

Backed.

Brazilian military planes dropped rifles, machine guns, and ammo to rebels in Santa Cruz. Argentina’s dictatorship lent support.

One week later, The Washington Post reported a U.S. Air Force major had assisted the plotters.

Of course, the State Department denied everything.

Banzer took power.

Unions were banned.

Civil rights were erased.

Torture centers were opened.

Political opposition vanished.

But hey, corporate mining contracts resumed.

Order, restored.

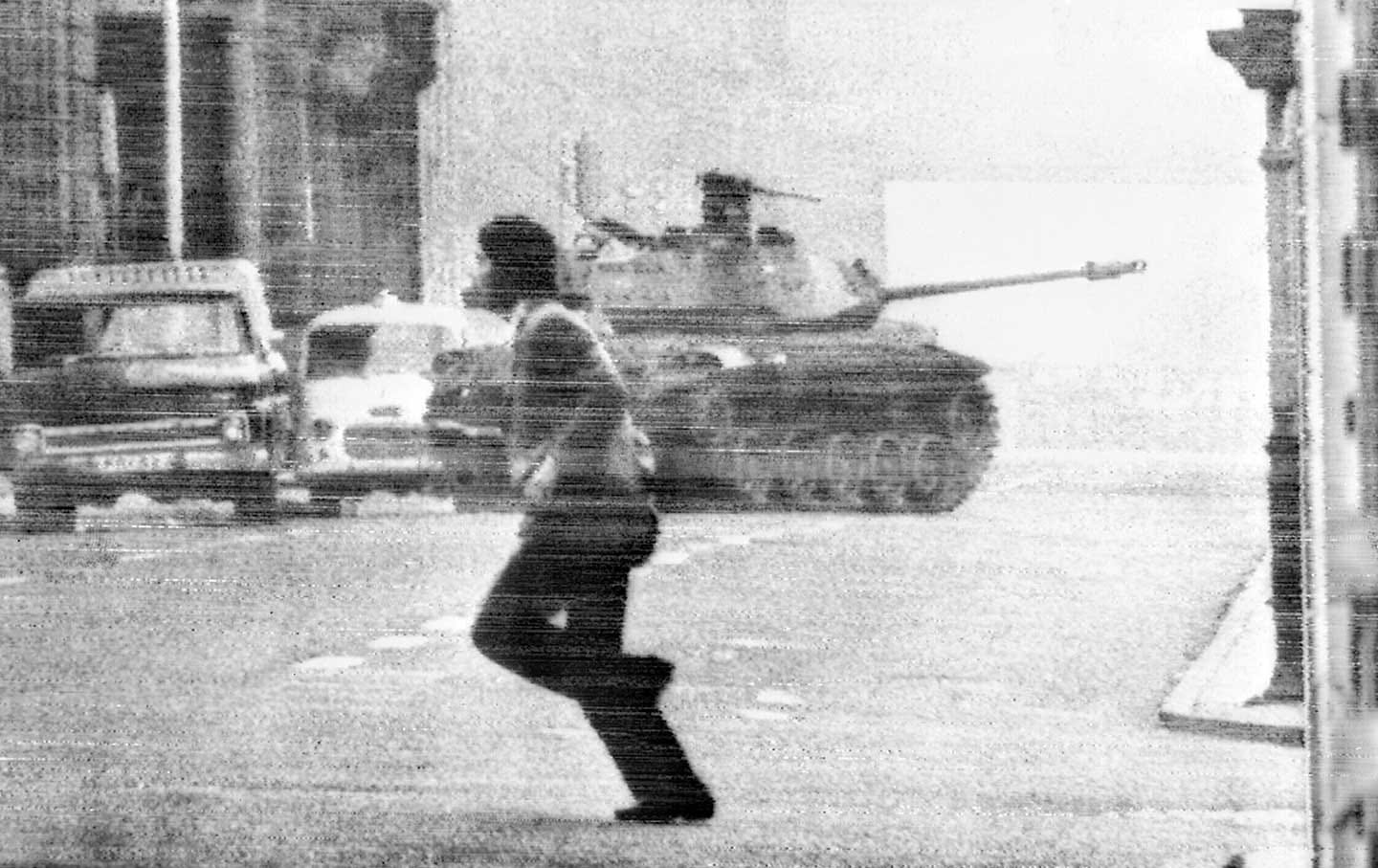

Chile (1973)

Salvador Allende was democratically elected—but a Marxist.

That was enough.

In 1970, President Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, initiated Project FUBELT, a covert CIA operation aimed at preventing Allende's inauguration and, failing that, destabilizing his government. The CIA funneled millions into Chile to sow chaos: funding opposition parties, orchestrating strikes, and disseminating propaganda through media outlets like El Mercurio.

On September 11, 1973, the Chilean military, emboldened by this support, bombarded the presidential palace. Allende died—officially by suicide, though the circumstances remain contentious. General Augusto Pinochet seized power, ushering in a 17-year dictatorship marked by brutal repression: over 3,000 killed, thousands more tortured or disappeared.

With Pinochet's rise, the Chicago Boys—a group of economists trained at the University of Chicago—implemented radical free-market reforms, transforming Chile into a neoliberal experiment.

While these policies spurred economic growth, they also entrenched deep social inequalities, the effects of which are still felt today.

The lesson?

When a leader prioritizes national sovereignty over U.S. interests, regime change becomes a policy tool.

Uruguay (1973)

Leftist guerrillas were gaining steam. The Tupamaros, once a fringe insurgency, were building popular support. And worse—the Frente Amplio, a broad left-wing coalition, was polling dangerously well ahead of the next election.

Washington panicked.

They’d already watched Chile fall to Allende in 1970. They weren’t about to let Uruguay follow suit.

So they didn’t wait for ballots.

They moved in with boots, wire, and shock cords.

The CIA had been helping Uruguay’s police since 1965—officially through USAID’s Office of Public Safety (OPS). But what they brought wasn’t standard-issue police training.

Enter Dan Mitrione, an American “advisor” stationed in Montevideo.

His classroom? The basement of his home.

His curriculum? Precision torture.

Electric shocks to mouths and genitals.

Pain calibrated “in the precise amount, for the desired effect.”

According to both former Uruguayan police and CIA operatives, Mitrione even ordered homeless people abducted off the streets—guinea pigs for his torture classes.

Some lived through multiple sessions.

Others didn’t.

In 1970, the Tupamaros kidnapped and executed him. But by then, the damage was done.

In 1973, the U.S.-backed military dissolved Uruguay’s Parliament.

Democracy out. Dictatorship in.

The CIA’s long game paid off.

The new regime cracked down hard—disappearing dissidents, torturing students, and eliminating the left as a political force.

The upside for the U.S.?

A tamed Uruguay. One that opened its economy to American capital, crushed labor unrest, and provided another compliant outpost in the Southern Cone—just as Operation Condor was getting underway.

No elections. No resistance. Just control.

Argentina (1976)

When Isabel Perón's government faltered, the military stepped in—with Washington's tacit approval.

The "Dirty War" commenced.

Up to 30,000 people disappeared—many abducted, tortured, and thrown from planes into the sea.

The junta became a key player in Operation Condor, targeting leftists across Latin America.

Washington's public stance?

Stability is good for markets.

Behind closed doors, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met with Argentine military leaders, urging them to act swiftly against their opponents before international outcry over human rights abuses could grow. He assured them of full U.S. support in their campaign—a position that clashed with the concerns of U.S. Ambassador Robert Hill, who feared the repercussions of backing a brutal regime.

The U.S. had anticipated a regime change as Perón's power waned. In early 1976, intelligence reports indicated that military dissatisfaction was so intense that a coup could occur at any time .

Washington's primary concern, of course, was protecting American economic interests—ranging from investments by Ford and General Motors to Exxon industrial centers .

Following the coup, the U.S. Congress approved $50 million in security assistance to the junta, with additional military aid and training programs in subsequent years . American corporations benefited from the suppression of labor unions and the establishment of a business-friendly environment under the dictatorship.

Once again, the U.S. prioritized geopolitical strategy and economic interests over human rights.

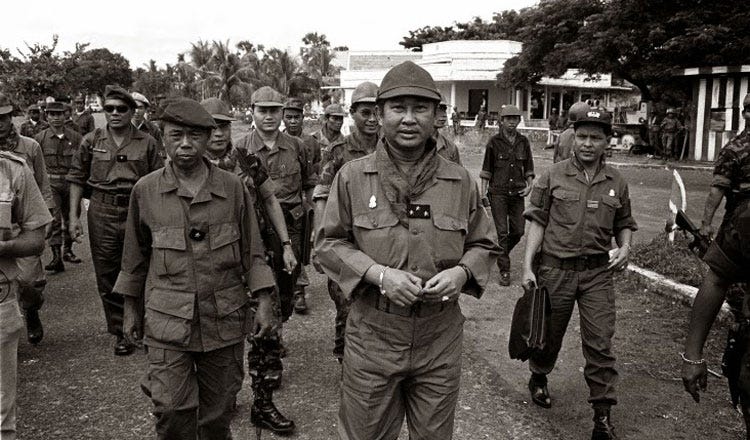

Cambodia (1970s–1980s)

Prince Sihanouk tried to stay neutral.

The CIA had other plans.

In December 1958, Ngo Dinh Nhu—Diem’s brother and CIA favorite—approached Dap Chhuon, Cambodia’s Interior Minister, to stage a coup against Sihanouk.

Chhuon received covert support from Thailand, South Vietnam, and the CIA.

But Sihanouk got wind of the plot.

Chhuon was captured and executed. Sihanouk accused the U.S. of orchestrating the attempt.

He was right.

Six months later, a parcel bomb—traced back to a U.S. military base in Saigon—was delivered to the royal palace. It killed his chief of protocol and nearly took out his parents.

Another message from Langley.

In March 1970, while Sihanouk was abroad, General Lon Nol seized power.

Sihanouk blamed the CIA. Evidence suggests he wasn’t wrong. U.S. military intelligence and Special Forces had been in contact with Lon Nol’s circle for months. The coup was greenlit, and Cambodia was dragged into the Vietnam War .

The result?

Civil war.

The U.S. backed Lon Nol with weapons and air support. The Khmer Rouge, once marginal, gained strength amid the chaos. By 1975, they took Phnom Penh.

Then came genocide. Up to 2 million dead.

But Washington wasn’t done. After Vietnam ousted the Khmer Rouge in 1979, the U.S. funneled millions to anti-Vietnamese resistance groups. Some of that aid ended up bolstering Khmer Rouge remnants.

The goal? Keep Vietnam bogged down. Stability be damned .

In the Cold War, the enemy of your enemy is your next proxy.

Hey! Where’s Guyana?

You may have noticed that the CIA did a lot of work in South America.

I mean, look at the map here:

But one country, surprisingly, you don’t see is Guyana.

Why is that?

You can follow that rabbit trail here:

From Gladio to Guyana: Jonestown and the CIA (Part 1/3)

What if the Jonestown deaths weren’t a mass suicide but a CIA cleanup? This deep dive connects the dots between Operation Gladio, Jim Jones’ shady past, and a massacre that silenced the truth—forever.

Yes. Jonestown was less Koolaid, and more CIA.

The "Police" of the World?

You ever notice how a lot of the CIA's actions looked like they were about “fighting communism”?

But if you squint a little harder, you see that "communism" was more like a convenient label—almost like a “Get Out of Jail Free” card.

The U.S. wasn’t really on the front lines of a moral battle.

They were playing world police, but they were also playing world bully.

Here's the thing:

The Red Scare wasn’t just a fear of communism. It was a fear of losing control. The U.S. was using communism as a scapegoat to justify any shady operation, any violent regime change, any economic hit job. As long as the public believed that communism was the bogeyman, the CIA could do whatever it wanted.

And this wasn’t just for ideological reasons. Oh no. Money was part of the equation too. The Cold War was profitable. Protecting U.S. interests—like oil, trade, or cheap labor—wasn’t just about containing an ideology. It was about keeping the gears of global capitalism turning. Not to mention that the drug trade is highly lucrative.

Scarface & the CIA: Oliver Stone’s Shocking Drug Trade Revelation

What if Scarface wasn’t just about a coke-fueled gangster’s rise and fall—but a veiled confession from inside the system?

But don’t think for a second that this all ended with the Vietnam War. Spoiler alert: It didn’t.

The Vietnam War wasn’t the finish line. It was just one chapter in a never-ending book of covert wars and regime changes.

Operation Condor? Nope, that was just one of many ways the U.S. stayed in the business of making sure Latin America stayed locked in a friendly grip—one military junta at a time.

The U.S. might’ve pretended to be the world’s peacekeeper, but the truth is, they were often the instigators.

The bad guys.

They weren’t stopping the spread of communism—they were advancing their own interests, wrapped up in a shiny, red bow.

But here’s the kicker: This behavior didn’t stop in the 1970s.

Far from it.

In Part 2, we’ll dive into how the game changed in the 1980s—and how those same old tactics evolved in the modern world. Spoiler: It didn’t get any cleaner.

The Blueprint Pt 2: The CIA’s Global Coup Machine (1980s–2020)

Let me guess—you thought the CIA stopped doing coups after the Cold War?

Colonel Towner is the goat. But yes, these were all CIA.

Operation Gladio you mean? CIA is only one tentacle of the Global Syndicate. https://rumble.com/v6rlvh5-operation-gladio-the-cia-secret-nato-army-wm-col-towner-watkins-8pm-edt.html?e9s=src_v1_upp

or https://open.spotify.com/episode/55nUns7obMJMJHwuMwdLZu