Informed Immunity: The Truth Behind Vaccines (Part 1/3)

Learn about the current vaccination schedule, public concerns, and the facts behind vaccine safety and scheduling.

Vaccinations have transformed public health by controlling and even eradicating serious diseases.

Smallpox - Eradicated in 1980; vaccine developed by Edward Jenner in 1796.

Polio - Nearly eradicated worldwide; significant control achieved in the 1980s with the oral vaccine, developed by Albert Sabin in 1961 and the earlier injectable vaccine by Jonas Salk in 1955.

Measles - Significant control achieved by the 1980s; vaccine developed by John Enders and Dr. Thomas Peebles in 1963.

Diphtheria - Largely controlled by the 1970s in developed countries; vaccine discovered by Gaston Ramon in the 1920s.

Rubella (German Measles) - Controlled in the 1970s; vaccine developed by Dr. Maurice Hilleman in 1969.

Mumps - Control achieved by the 1970s; vaccine also developed by Dr. Maurice Hilleman in 1967.

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) - Controlled in the 1990s; vaccine introduced in 1985.

Today, we have recommended vaccination schedules that begin in infancy and extend through adulthood. However, with more vaccines being added over recent decades, some people have raised concerns about whether the current schedule is truly necessary, or if it may present risks.

This series, Informed Immunity, dives into modern vaccination schedules, exploring their history, effectiveness, and the safety concerns that some parents and individuals have today. Each article in the series addresses a different aspect of vaccination, from how and why schedules were developed to potential risks and the latest scientific research.

This particular article offers an overview of the current vaccination schedule, explaining the rationale behind its structure and shedding light on ongoing debates about vaccine safety and efficacy.

What Is the Current Vaccination Schedule?

The vaccination schedule is a planned series of immunizations that protects individuals from preventable diseases throughout their lives. Health organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) establish these schedules, updating them periodically based on new scientific insights and emerging health threats. Here’s how these guidelines are set and updated.

Who Sets the Schedule?

In the U.S., the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) sets the vaccination schedule. This committee, composed of healthcare professionals and infectious disease experts, reviews extensive data to determine when and how often vaccines should be given. They consider public health goals and current disease trends in making these decisions.

How Often Is It Updated?

The vaccination schedule is reviewed and updated every year. Updates consider new scientific research, new vaccine developments, and shifts in public health needs. For instance, when COVID-19 vaccines became available, they were added to the adult and adolescent schedules. This flexibility ensures the schedule remains relevant and effective.

A Snapshot of the Common Vaccines in Today’s Schedule

Vaccines are recommended across different life stages. Here’s a quick look at the common vaccines included in today’s schedule.

Routine Vaccinations for Infants and Children

From birth to age five, infants and children receive vaccines for diseases like measles, mumps, rubella (MMR), diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP), and hepatitis B, among others. These early vaccinations are said to be critical for building immunity when children are most vulnerable.

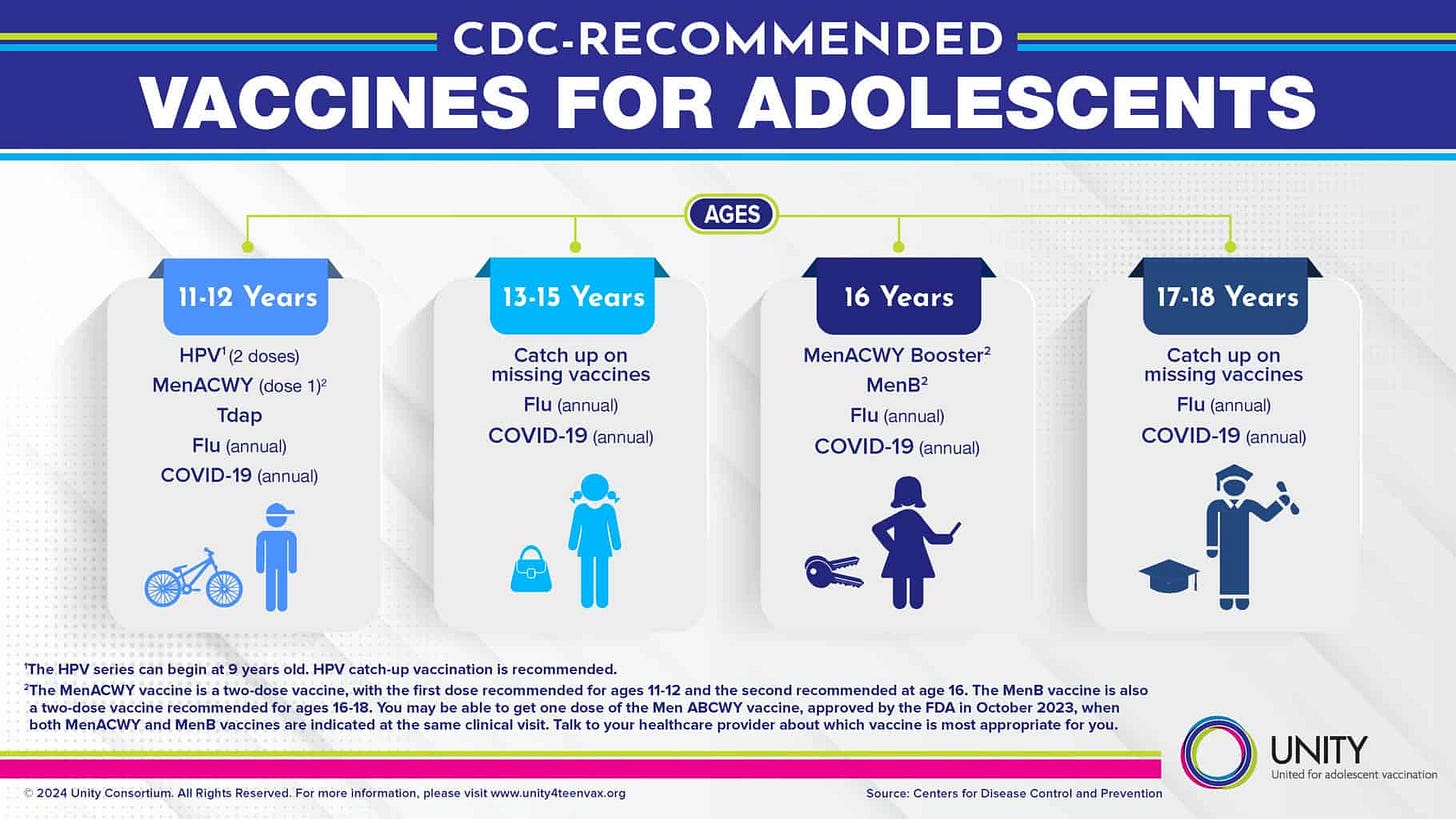

Adolescent and Adult Vaccination Recommendations

For adolescents, vaccines like the human papillomavirus (HPV) and meningococcal are typically recommended. For adults, booster shots and immunizations such as influenza and shingles vaccines are suggested. This ongoing schedule helps ensure that people remain protected as they age, reducing the potential for disease outbreaks.

So, if you follow the recommended schedule by the CDC, here’s how it breaksdown:

Approximately 30-35 doses between birth to 6 years.

Hepatitis B: 3 doses

Rotavirus: 2-3 doses (depending on the type of vaccine)

DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis): 5 doses

Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b): 3-4 doses (depending on the type of vaccine)

Pneumococcal: 4 doses

Polio (IPV): 4 doses

MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella): 2 doses

Varicella (Chickenpox): 2 doses

Hepatitis A: 2 doses

Influenza (Flu): Annual dose each year (up to 6 doses from 6 months to 6 years)

COVID-19: 1 or more doses, depending on health status

Approximately 20-25 doses between 7 - 18 years.

Tdap (Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis): 1 dose

HPV (Human Papillomavirus): 2-3 doses (depending on the age at first dose)

Meningococcal ACWY: 2 doses

Meningococcal B: 2 doses (if indicated)

Influenza (Flu): Annual dose each year (up to 12 doses)

COVID-19: 1 or more doses, depending on health status

Approximately 75-85 doses during adulthood:

Td/Tdap (Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis): Every 10 years, 1 dose per decade (approx. 5-6 doses over a lifetime)

Influenza (Flu): Annual dose (approximately 60 doses from 19-79 years)

COVID-19: 1 or more doses, depending on updated recommendations

Shingles: 2 doses (recommended at 50+ years)

Pneumococcal: 1-2 doses (recommended at 65+ years or earlier for high-risk individuals)

HPV: 2-3 doses (recommended for adults who didn’t receive it in adolescence)

MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella): 1-2 doses (for adults without immunity)

Hepatitis A and B: 2-4 doses each (depending on travel, health conditions, and exposure risk)

RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus): 1 dose (if indicated in older adults)

Approximately 125-145 doses over a lifetime.

This is not hypochondriacs. This is the CDC recommendations.

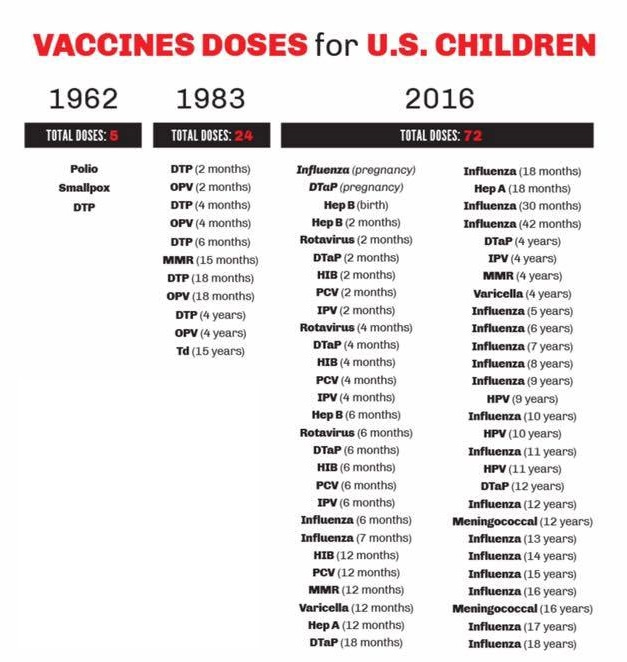

If this number seems high to you, it should. At least, historically speaking.

Why Is There a Growing Concern Around Vaccination Schedules?

Over recent decades, the number of vaccines recommended by health organizations has dramatically increased. This raises questions about the necessity of every vaccine, leading to broader concerns about their overall safety and effectiveness.

An Increase in Vaccine Numbers Over Time

The increase in the number of recommended vaccines reflects advancements in preventive healthcare. However, some parents worry about the volume and potential risks of administering multiple vaccines at once, which may overwhelm a young child’s developing immune system.

So what made the jump?

Several factors, more than likely. But one big one was the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA) of 1986.

It arose from a period of growing concerns over vaccine safety, particularly related to the DTP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis) vaccine, which led to numerous lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers. These lawsuits created financial strain on vaccine manufacturers, threatening the “stability” of the vaccine supply.

So, rather than investigate on a federal level, NCVIA was passed.

National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act

The NCVIA established the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) as a no-fault alternative to the traditional legal system for resolving vaccine injury claims.

Under VICP, individuals or families claiming vaccine injury can apply for compensation without going through lengthy lawsuits. This system is touted as “helping” people avoid the complexities of proving fault in court.

QUICK BACKSTORY:

One reason (touted by the pharmaceutical companies) that NCVIA was passed was because, with the lawsuits they were having, it was making their liability insurance rates go up. This in turn “forced” them to raise the price of their drugs.

Obviously, no one wants high-priced drugs.

So the NCVIA was passed to avoid any more legal fees (or at least a good chunk of them). But, there was still the matter of the fund. Where would that money come from?

From the insurance companies. Or rather, from you.

The NCVIA funds its Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) through a federal excise tax on vaccines. An excise tax of $0.75 per dose is applied to each vaccine covered under the VICP. So, while a single-dose vaccine for one disease (e.g., Polio) incurs a $0.75 tax, a combination vaccine (like MMR) would incur a $2.25 tax.

So, , the excise tax is incorporated into the price of vaccines, which is ultimately paid by the recipient or their insurance provider.

Geniuses. Evil geniuses. Not only did they solve their avalanche of legal problems, but then they started a slush fund to address any future “missteps” and make the recipients of the vaccines pay for it.

Side Effects and Safety Concerns

“Any vaccine can cause side effects.

For the most part these are minor (for example, a sore arm or low-grade fever) and go away within a few days.”

So, is that true? Just some soreness? Kind of.

Whether or not vaccines are beneficial in themselves is a discussion for another time. Assuming they are beneficial, it’s not the vaccine itself that’s the problem.

It’s how it’s made.

In part 2 of this series, we’ll dive into how vaccines have changed and why the rise of Autism has been connected to MMR and other “vaccine injuries.”

Informed Immunity: Autism Anonymous (Part 2/3)

When you think about vaccines, you probably imagine a little pinch, a Band-Aid, and a sigh of relief knowing you're protected.