Trump's Plan to Demolish the DOE: A Deep Dive (Part 3 of 3)

Trump’s Bold Plan to Demolish the DOE: Can Local Control Finally Fix America’s Schools?

In the first two parts of this series, we explored the creation of the Department of Education (DOE) and its deep ties to teachers' unions, particularly the NEA and AFT.

You can read them here if you haven’t already:

We saw how the DOE became a powerful force in shaping federal education policy, largely driven by union influence, and how the focus often shifted to protecting and serving teachers rather than students.

Now, in Part 3, we’ll dive into Trump’s plan to abolish the DOE, returning control to states and local districts.

Is dismantling the DOE a radical idea, or could it actually lead to better outcomes for students?

Let’s break it down.

Trump’s Vision: Local Control and Flexibility

Why does Trump want to abolish the DOE? His rationale is pretty straightforward:

Local control over education means:

More flexibility

Less bureaucracy

The ability for states to tailor their education systems to the specific needs of their communities.

The argument is that a one-size-fits-all federal system doesn’t work in a country as diverse as the U.S. What students in California need might be completely different from what students in Oklahoma need.

Under Trump’s plan, states would have the freedom to set their own standards for curriculum, testing, and accountability.

This would allow local leaders to implement innovative programs that directly respond to their students’ unique needs, without waiting for federal approval. His argument is that the DOE often gets in the way of real progress by imposing federal standards that don’t always fit and, worse, stifles creativity and innovation.

The Pros and Cons of Abolishing the DOE

The Pros:

Local Flexibility: States and local districts can experiment with different methods of teaching and evaluation. A state like Vermont might focus on holistic approaches, while Texas might emphasize STEM. The power lies in their hands.

Reduction of Bureaucracy: One of the biggest criticisms of the DOE is the red tape it creates. Schools must navigate a maze of federal regulations to secure funding, which can slow down progress. Eliminating the DOE means less paperwork, more action.

Innovation in Education: With fewer federal restrictions, schools could adopt innovative approaches like project-based learning or alternative assessments that better measure students’ skills. This gives room for schools to focus on 21st-century learning, rather than outdated testing methods.

The Cons (and rebuttals):

Potential for Inequality: Without federal oversight, there’s a risk that states might underfund or neglect certain populations. Historically, federal involvement has helped ensure that low-income and minority students get the resources they need. Will states like Mississippi invest in all their students equally, or could the disparities grow?

Rebuttal:

This concern overlooks the progress many states have already made in addressing inequities on their own. For instance, New Jersey ranks second in the nation for student achievement and graduation rates due to its progressive school finance reforms. The state allocates 20% more per pupil in districts with at least 30% of students in poverty, showing that state-level efforts can effectively target resources where they’re most needed.

Additionally, Mississippi—often cited as a state that lags behind—has proven the opposite with its successful education reforms. The state's literacy overhaul in 2013 led to significant improvements in fourth-grade literacy, particularly among Black students, with their scores improving faster than those of their White peers. This demonstrates that state-driven initiatives can indeed reduce disparities when focused on research-backed strategies.

So, can more be done about racism? Sure. But that’s not the responsibility of the state, that’s the responsibility of the parents. You can’t legislate morality.

Loss of Federal Funding: The DOE provides states with a lot of money—over $68 billion in federal aid in 2020 alone. Abolishing the DOE could mean losing this vital funding, which many school districts rely on, especially in poorer areas. How would states fill this gap?

Rebuttal:

The Department of Education isn't the main source of funding for U.S. schools. Prior to the influx of pandemic relief funds, the federal government contributed just around 8% to K-12 education budgets. In recent years, this share has risen to about 11%.

Abolishing the DOE does not be abolishing federal funding. Funding programs could be moved to other federal agencies. Marguerite Roza is the director of the Edunomics Lab, a research center focused on education finance policy at Georgetown University. “I don’t think that schools would suddenly lose money,” she said.

Lack of Consistent Standards: With each state setting its own standards, how do we ensure that students across the country receive a quality education? Without a national framework, there’s a risk of educational chaos, where a high school diploma in one state might not mean the same thing in another.

Rebuttal:

This is based on an outdated view of how education is managed in the U.S. While it’s true that each state sets its own standards, states have shown they can successfully implement high-quality frameworks tailored to their local needs, often without the need for federal oversight. Additionally, tests such as the ACT and SAT are still standardized across the country.

There’s no evidence to suggest that a one-size-fits-all federal approach is inherently better for students. Educational needs and priorities vary significantly by region, so allowing states to adapt their standards ensures that education is relevant and responsive to their unique student populations. The success of states like New Jersey and Massachusetts in maintaining high educational outcomes while setting their own rigorous standards proves that decentralized approaches can still deliver quality education across the board.

Federal mandates have not always led to improved outcomes. The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) showed that a national framework could often be too rigid, failing to account for the diversity of student needs across different states.

The key is not uniformity but accountability. States are fully capable of upholding educational standards if given the flexibility to innovate and adapt to their students’ needs while ensuring robust systems of accountability and oversight. A national framework doesn’t necessarily guarantee quality—it’s the practices within states that make the real difference.

So what’s the real problem?

Why did Trump even talk about abolishing the Department of Education?

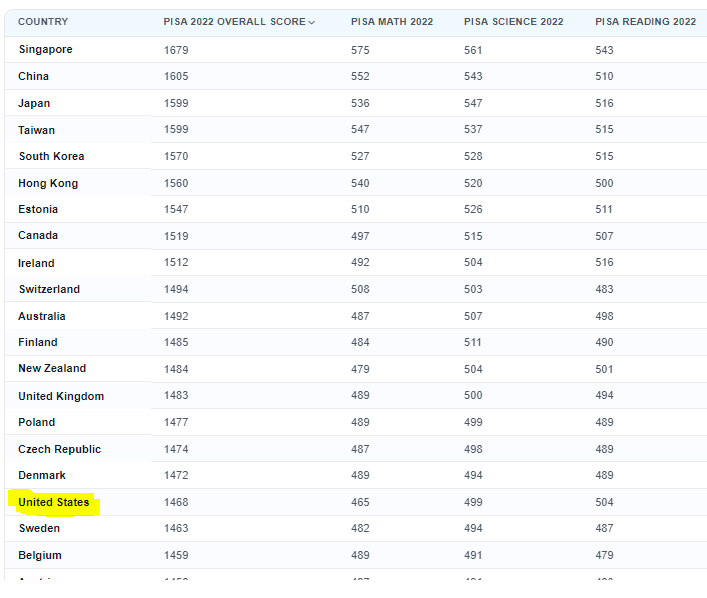

In his spaces conversation with Elon over X, Trump said that the US ranked horribly when it came to education. More than likely, he was referring to the PISA test (Programme for International Student Assessment).

PISA results from 2022 from 80 countries. We are in 18th place.

The original Department of Education Organization Act of 1979 specifically outlined the purpose of the department:

Therefore, the purposes of this Act are—

to strengthen the Federal commitment to ensuring access to equal educational opportunity for every individual;

to supplement and complement the efforts of States, the local school systems and other instrumentalities of the States, the private sector, public and private educational institutions, public and private nonprofit educational research institutions, community-based organizations, parents, and students to improve the quality of education;

to encourage the increased involvement of the public, parents, and students in Federal education programs;

to promote improvements in the quality and usefulness of education through federally supported research, evaluation, and sharing of information;

to improve the coordination of Federal education programs;

to improve the management and efficiency of Federal education activities, especially with respect to the process, procedures, and administrative structures for the dispersal of Federal funds, as well as the reduction of unnecessary and duplicative burdens and constraints, including unnecessary paperwork, on the recipients of Federal funds; and

to increase the accountability of Federal education programs to the President, the Congress, and the public

So, let’s look at how well we’ve done, using my very professional rubric (feel free to disagree).

Rubric for the DOE’s Performance:

Ensuring Access to Equal Educational Opportunity: 3/5

Progress: Achievement gaps in reading and math between racial groups have narrowed. Federal programs like Title I have targeted disadvantaged schools effectively.

Challenges: Significant disparities in education persist across socioeconomic lines, particularly in underserved urban and rural areas.

Supplementing State and Local Efforts to Improve the Quality of Education: 2.5/5

Progress: Federal programs like IDEA and ESEA have supplemented state efforts, providing necessary funding to under-resourced schools.

Challenges: Large-scale federal interventions, like No Child Left Behind and Common Core, failed to yield expected improvements.

Encouraging Public and Parental Involvement: 2/5

Progress: Policies under ESSA sought to increase local control and parental engagement.

Challenges: Parental involvement remains inconsistent, particularly in low-income areas where engagement is critical.

Promoting Educational Improvements through Federally Supported Research: 3/5

Progress: Federally funded research has led to advancements in areas like special education, technology, and learning strategies.

Challenges: A gap exists between research and classroom implementation, with many schools not adopting evidence-based practices.

Improving Coordination of Federal Education Programs: 3/5

Progress: Federal program coordination has improved, especially in grant administration.

Challenges: Conflicting state and federal priorities often hinder seamless program coordination.

Improving Management and Efficiency of Federal Education Activities: 2.5/5

Progress: Simplifications in processes like student aid have occurred.

Challenges: Persistent complaints about bureaucracy and paperwork burdens hamper perceived efficiency.

Increasing Accountability of Federal Education Programs: 3/5

Progress: Programs like No Child Left Behind and ESSA introduced strong accountability measures.

Challenges: Despite accountability efforts, many performance metrics show little progress, with some areas of education remaining stagnant.

Overall Score: 2.7/5

So, the bottom line is it’s not working. The DOE is not accomplishing what it set out to do. So, why keep it? Trump’s plan is to turn the responsibility of education back over to the states. With a smaller infrastructure and less red tape, districts and schools will be able to innovate more quickly. In today’s world, speed is not just a good thing - it’s a necessity.

Where do we start?

One major concern with abolishing the DOE is the loss of federal funding. As outlined before, that’s highly unlikely to happen.

But what if the solution lies not in the funding but in reallocating existing funds more effectively?

After all, the United States has one of the highest per-student expenditures in regards to education.

Let’s take a look at where education dollars go now:

Instruction: Roughly 60% of school funding goes toward classroom instruction.

Administration: About 11% is spent on administrative costs, often seen as a bloated sector.

Other areas include support services, maintenance, and transportation.

Critics argue that too much money is wasted on administrative bloat, while students see relatively little improvement in classroom resources or teacher quality.

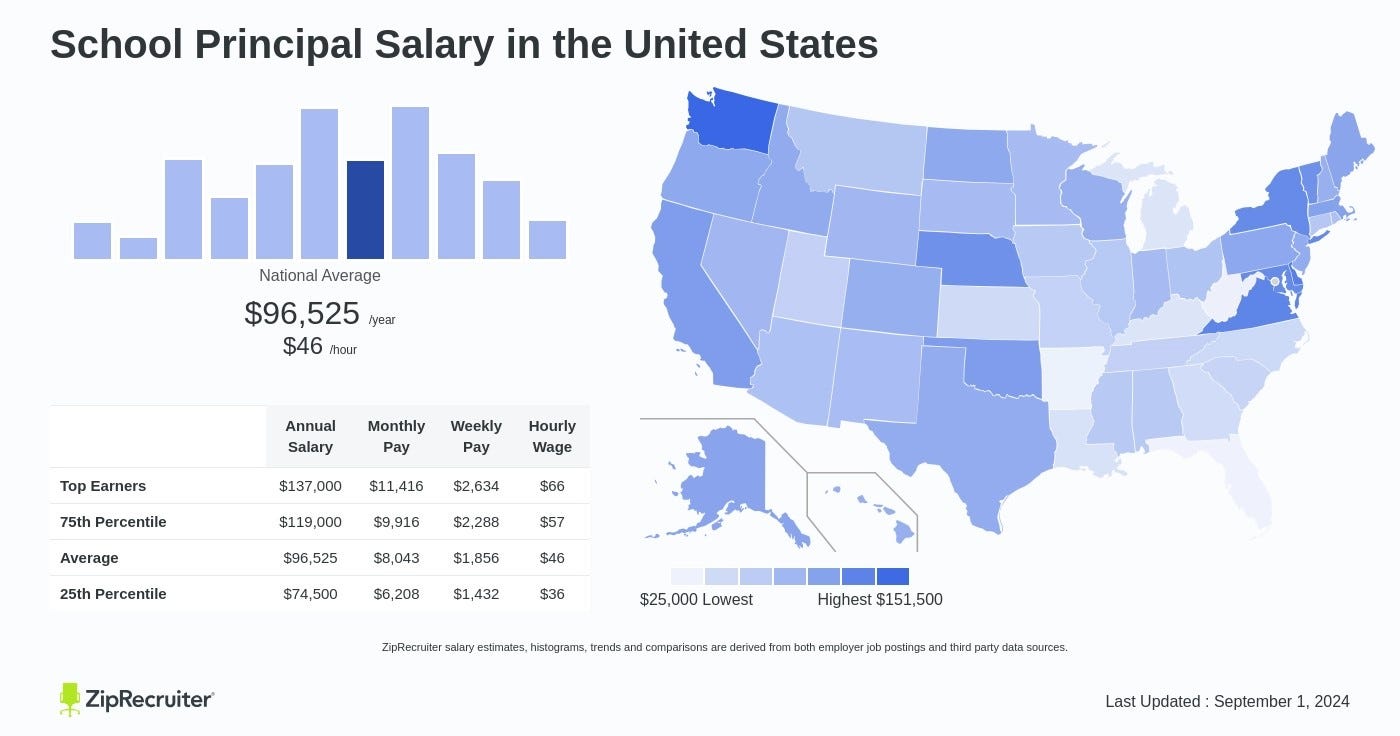

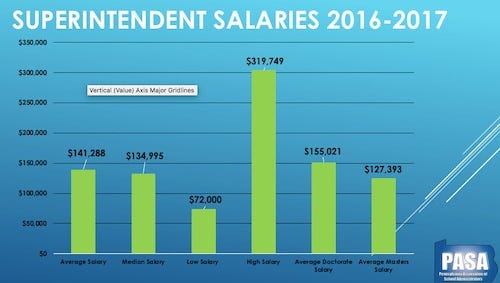

The average superintendent salary in 2016-17 in Pennsylvania was around $141,000. The median salary was around $135,000.

By the way, look at the 2019 salaries for the New Jersey NEA Chapter (one of the largest NEA state chapters).

Yeah. That’s over $2,000,000.

Whether or not principals and superintendents make too much money, I leave up to you to decide. Regardless, if states took control of their education systems, they could reallocate funds—directing more money to teacher salaries, classroom resources, and technology, and less to administrative overhead.

By investing in teachers and direct classroom instruction, states could potentially provide a better education with less federal interference. For example, streamlining administrative costs could free up millions for schools to improve facilities, reduce class sizes, or implement new programs.

The Future Without the DOE: A Tailored Approach

Imagine a future without the DOE—where education is a state-controlled system. How would this look in practice?

Take California and Oklahoma as examples. California might choose to emphasize progressive education reforms, implementing green initiatives in schools or focusing on arts and culture. Oklahoma, on the other hand, might prioritize vocational training and agricultural education, responding to the local economy’s needs. Texas may focus on partnerships with the oil and gas industry.

Without the DOE imposing national standards, these states can craft tailored education systems that make sense for their populations. Local educators would have the power to innovate.

Most importantly, parents would have a direct line to the people making decisions for their children.

But this tailored approach also comes with responsibility. States would need to ensure that every student—regardless of their background—gets a quality education. And without federal intervention, it will be up to the states to monitor and improve outcomes.

The Benefits of Dismantling the DOE

Ultimately, abolishing the DOE offers the opportunity to streamline education, cutting through federal bureaucracy and allowing states to implement more localized, innovative approaches. While the risk of inequality is real, rethinking how education funds are allocated—particularly reducing administrative bloat—could lead to a system that better serves students across the country.

What would that future look like? It’s time to imagine an education system that is built from the ground up—one that empowers teachers, parents, and most importantly, students.

![U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics [2024]: per Pupil + Total U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics [2024]: per Pupil + Total](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!MQiL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1499db84-68b3-4121-978f-81207ed59e0a_800x526.png)