Villain by Design: How Russia became the Boogeyman of the West

Russia is not the bad guy—discover how Cold War fear, NATO expansion, and post-WW2 politics made Russia the West’s boogeyman, and discover who the real villain might be.

For decades, the dominant Western narrative has painted Russia as the boogeyman—a relentless, power-hungry adversary bent on undermining democracy and spreading chaos. But what if the story we've been told isn't the whole truth? What if Russia is not the bad guy?

Following World War II, the United States emerged not only as a global superpower but also as a nation with a growing appetite for influence. With no common enemy left after the Axis powers fell, America needed a new adversary. The Soviet Union, conveniently authoritarian and ideologically opposed, became the perfect foil. But the roots of this rivalry run far deeper than just politics—they touch military decisions, cultural fears, broken promises, and geopolitical chess games that continue today.

Let’s take a journey through history and challenge the mainstream perspective.

Why the West Needed a Villain After WWII

The Vacuum of Victory

World War II ended with Nazi Germany defeated and imperial Japan brought to its knees. But peace didn’t mean unity. With the world’s major players scrambling to reshape the global order, alliances shifted and new threats were manufactured—sometimes more for convenience than truth.

Enter the Cold War

When two superpowers emerge from a war-torn world, one of them is bound to become "the bad guy." The U.S. had capitalism, Coca-Cola, and Hollywood. The USSR had communism, collectivism, and steel-gray realism.

It wasn’t long before these contrasts were weaponized into fear.

General Patton and the Missed Opportunity

Patton’s Post-War Perspective

General George S. Patton, the gruff, no-nonsense commander, believed the U.S. should have continued its march east—right into Soviet territory. He saw Stalin's Russia not as an ally but a looming threat.

Patton’s proposal? Strike before the Soviets became too strong.

“Hell, why do you care what the Goddamn Russians think? We are going to have to fight them sooner or later within the next generation. Why not do it now while our army is intact and the damn Russians can have their hindends kicked back into Russia in three months? We can do it ourselves easily with the help of the German troops we have, if we just arm them and take them with us; they hate the bastards.”

Why Washington Said No

The U.S. was exhausted, and the appetite for another war simply didn’t exist. The alliance with the USSR, fragile though it was, still held some diplomatic value. But in not taking Patton seriously, the U.S. may have inadvertently allowed decades of hostility to fester.

Or was it on purpose?

Was the US keeping the USSR alive enough to have a ready threat to call upon in the name of “National Security” in order to justify whatever decisions or operations they wanted?

Birth of the Cold War

Two Ideologies, One World

Capitalism versus communism.

Individual freedom versus state control.

These ideological extremes gave both sides reasons to mistrust and undermine one another. But ideology alone didn’t drive the narrative—fear did.

From newsreels to textbooks, the USSR was cast as a brutal, soulless machine. The U.S. needed Americans to believe they were under constant threat—because fear keeps a population compliant.

The Truman Doctrine and Containment

In 1947, President Truman declared that the U.S. would support nations resisting communism. This open-ended promise justified decades of intervention, all under the banner of keeping Russia in check.

The Red Scare and Internal Fear-Mongering

McCarthyism’s Long Shadow

Senator Joseph McCarthy turned paranoia into policy. Accusations flew. Careers ended. Families were torn apart—not by Russian agents, but by American suspicion.

But his policy sounds pretty good, doesn’t it?

I mean, “dislodge traitors.” That makes sense.

But here’s the rub: Who’s the traitor? Who is a communist?

The answer: Anyone the US Government wants (or rather, doesn’t want).

Fear as a Political Weapon

Calling someone a communist became a convenient way to ruin lives. The witch hunts of the 1950s showed that America's fear of Russia wasn’t just external—it was deeply internalized.

Films like Red Dawn and The Hunt for Red October cemented the USSR as the ultimate villain. Art imitated fear. Fear became identity. I mean, just look at the slew of some of the films that painted Russia is the ultimate bad guy, on par with Nazis.

The Iron Curtain (1948) – Based on the true story of a Soviet code clerk who defects to Canada. Soviet intelligence is painted as paranoid, oppressive, and morally vacant.

The Red Menace (1949) – A former American GI falls in with a communist cell, only to discover their anti-American treachery. The Soviets are portrayed as manipulative infiltrators targeting U.S. society.

I Married a Communist / The Woman on Pier 13 (1950) – A man with a hidden communist past is blackmailed by Soviet agents to sabotage American interests. The USSR is shown as coercive, subversive, and morally corrosive.

Invasion U.S.A. (1952) – Soviet forces launch a surprise invasion of the United States, destroying major cities. The film plays directly into Cold War fears, portraying Russians as ruthless and expansionist.

Dr. Strangelove (1964) – A dark satire about nuclear war and Cold War paranoia. Though satirical, it depicts the USSR as a militarized threat locked in a deadly standoff with the West.

The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1965) – A British agent gets caught in a bleak world of East-West espionage. While morally complex, the Soviets are shown as cold, deceptive manipulators of ideology.

The Kremlin Letter (1970) – A CIA agent is sent into Moscow to retrieve a sensitive letter, facing Soviet agents in a deadly game. The KGB is portrayed as brutal, cunning, and fanatically ideological.

Firefox (1982) – Clint Eastwood plays an American pilot sent to steal a top-secret Soviet fighter jet. The Soviets are high-tech, paranoid, and deeply authoritarian.

Red Dawn (1984) – Soviet and Cuban forces invade the American heartland, prompting a guerrilla resistance by teenagers. The USSR is the main villain, depicted as aggressive and unrelenting.

Rocky IV (1985) – American boxer Rocky Balboa fights Soviet champion Ivan Drago in a Cold War symbol match. Drago and his handlers are shown as emotionless, state-engineered products of a hostile superpower.

Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) – Rambo returns to Vietnam to rescue POWs but ends up fighting Soviet soldiers backing the Vietnamese. The Soviets are framed as secret puppet-masters and war criminals.

The Living Daylights (1987) – James Bond uncovers a KGB operation to manipulate international arms deals. The KGB is portrayed as duplicitous and globally dangerous.

The Hunt for Red October (1990) – A Soviet submarine captain defects to the U.S. with a top-secret nuclear sub. While not all Russians are villains, the Soviet military establishment is painted as paranoid and reckless.

Air Force One (1997) – Russian ultra-nationalist terrorists hijack the President’s plane. The villains are hardline Soviets seeking a return to Cold War dominance.

Salt (2010) – A CIA agent is accused of being a Russian sleeper spy. Russian intelligence is portrayed as a shadowy, ongoing threat to U.S. stability and security.

The Courier (2020) – Based on the true story of a British businessman turned spy during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Soviet secrecy and global brinksmanship are central to the film’s tension.

NATO Expansion and Broken Promises

This article is not an apologia for the Soviet Union. That regime was responsible for undeniable atrocities: the Holodomor (a state-induced famine in Ukraine that killed millions), the Great Purge under Stalin (where nearly 700,000 people were executed), and the sprawling Gulag system, which imprisoned and brutalized millions more.

The Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe was repressive, marked by the suppression of uprisings in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968). These acts were cruel, calculated, and authoritarian. They deserve full historical condemnation.

What this article highlights, however, is that the United States—despite recognizing the Soviet Union as a looming threat—chose not to act militarily at the moment it arguably could have.

Instead, it allowed the USSR to grow in strength, then used the specter of Soviet power to justify decades of covert warfare, regime changes, and morally dubious operations: from Operation Condor in South America, to Operation Gladio in Europe, to the Vietnam War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and countless other interventions.

The Soviet Union became the perpetual excuse, not just for defense, but for domination.

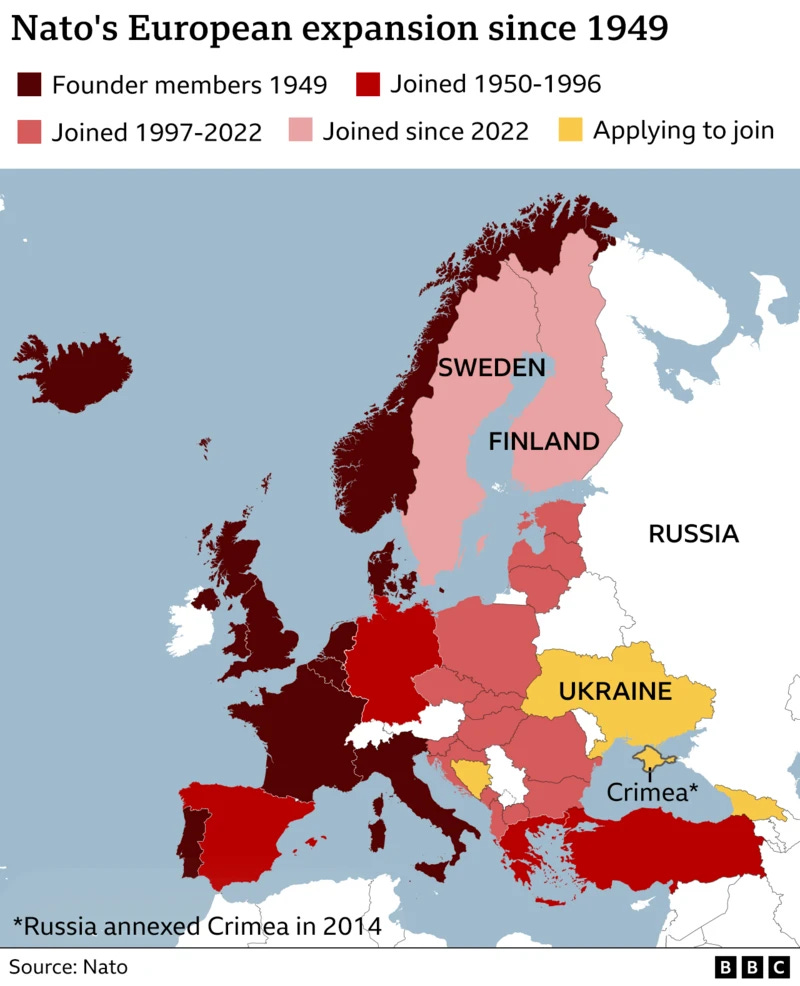

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the U.S. made verbal assurances that NATO wouldn’t expand "one inch eastward."

This was crucial for Russian security concerns.

Reality Hits Different

Instead of pausing though, NATO grew—Poland, Hungary, the Baltic States. From the Russian perspective, it felt like betrayal.

And betrayal breeds resentment.

When Ukraine flirted with NATO membership, Russia reacted. Western leaders called it aggression. Russia called it self-defense.

The truth?

Probably somewhere in between. But how bad is Russia?

Are their citizens living in fear? Starving? Zombies that march to the beat of a neo-Stalinist regime?

Post-Soviet Russia: What Really Happened after 1991?

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Western leaders declared it a victory for freedom—capitalism triumphant over communism. But inside Russia, the fall felt more like free fall. What followed wasn't liberation—it was economic chaos, social unraveling, and a desperate struggle to redefine identity.

The 1990s: Democracy or Devastation?

Western advisors flooded in to help “modernize” the Russian economy—what they actually delivered was shock therapy: rapid privatization, market liberalization, and asset stripping. State-owned industries were handed off to connected insiders, birthing the oligarch class almost overnight. Inflation soared. Savings vanished. In 1992 alone, GDP contracted by 14.5%, and by the end of the decade, over 40% of Russians were living below the poverty line.

Elections were held, but they were far from free. Boris Yeltsin, backed openly by U.S. political consultants and IMF cash, barely held power through a volatile period marked by corruption, mafia wars, and mass protests.

Turns out that Russia (under Yeltsin) had siphoned off funds (to the tune of $10B+) into Cayman Island accounts.

According to senior Russian parliamentary sources, the siphoning-off of western aid stretched back five years, and was designed to boost Yeltsin's chances of re-election in 1996.

—The Guardian, 1999

Eventually, Yeltsin’s term was over.

When Vladimir Putin took over in 2000, many Russians didn’t see him as a tyrant—but as a stabilizer. Even the US said the election was “reasonably free and fair.”

Putin was genuinely popular, with “spectacular” increases in approval ratings in the fall of 1999.

—US Embassy

But what made Putin so popular?

One word: Chechnya.

Chechnya and the Rise of Putin

In the late 1990s, Russia was reeling from its failed First Chechen War (1994–1996), where a demoralized and underfunded Russian military was humiliated by a ragtag insurgency.

The peace that followed was uneasy at best—Chechnya became a lawless zone of warlords, kidnappings, and radical Islamist cells.

Then, in 1999, a series of apartment bombings rocked Moscow and other cities, killing over 300 civilians and plunging the nation into panic. Blame was quickly placed on Chechen terrorists, and within days, Putin—then the recently appointed Prime Minister—promised swift and brutal retaliation.

He launched a second war with overwhelming force and unapologetic rhetoric, vowing to "waste the terrorists in the outhouse." To many Russians, desperate for order after a decade of lawlessness, this was the first sign of strength they’d seen from the Kremlin in years.

But not everyone accepted the official story.

From the beginning, questions circled.

Chechnya, Jihad, and the Battle for the Pipeline

In the early 1990s, as the Soviet Union crumbled and Russia struggled to stay upright, the eyes of the West shifted to a different kind of conquest:

Energy supremacy.

The Caspian Basin, nestled between Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, was discovered to hold vast untapped reserves of crude oil and natural gas—trillions of dollars’ worth. The United States, led by oil-centric policy architects under President George H. W. Bush, saw opportunity.

It should also be noted that Bush’s brother had a motive too.

Chevron struck early deals with Kazakhstan, while former covert operatives like Heinie Aderholt, Richard Secord, and Ed Dearborn (veterans of U.S. black ops in Laos and Nicaragua) arrived in Baku, Azerbaijan, posing as executives for MEGA Oil.

Backed by Washington, they pushed for a pipeline that would route oil from Azerbaijan through Georgia and into Turkey, deliberately bypassing Russian territory. To ensure that plan could take root, chaos had to be cultivated where Russian energy control was strongest:

Meanwhile, under the Clinton administration, a powerful coalition of American elites began shaping foreign policy around energy extraction.

In 1995, the U.S.-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce was founded, led by heavyweights:

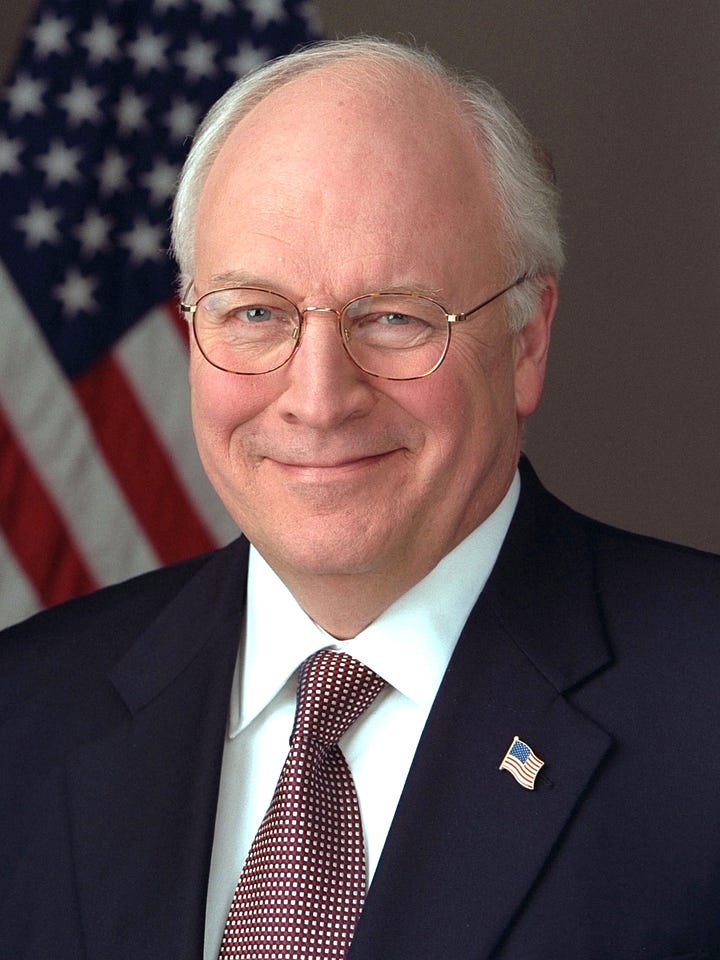

Bush Sr.’s Secretary of State

then chairman and CEO of Halliburton, the world’s 2nd largest oil company)

Primary organizer of The Trilateral Commission

Mentor to Madeleine Albright

Member of both the Council on Foreign Relations and the Bilderberg Group

Championed U.S. involvement in prolonged conflicts like Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos

Authorized secret carpet-bombing of Cambodia (Operation Menu)

Orchestrated or approved support for the CIA-backed overthrow of democratically elected Chilean President Salvador Allende

Authored National Security Study Memorandum 200 (NSSM 200) in 1974, which emphasized population growth in the Third World as a national security threat

Gave green light to Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor in 1975

Regular attendee and influencer in secretive elite gatherings like Bilderberg, Trilateral Commission, and Davos

Cheney’s company, Halliburton, had already begun geophysical testing in the region. In 1998, Bill Clinton tapped Richard Morningstar and Matt Bryza to develop a U.S. energy strategy for the Caucasus—specifically, one that would sideline Russia entirely.

There was one problem: the only pipeline running west from Baku passed directly through Grozny, the capital of Chechnya.

Manufacturing a Warzone

Historically, Chechnya was a land of moderate Sufi Islam, but the 1990s saw a wave of radicalization—and it didn’t happen organically.

According to multiple sources, including former U.S. and Russian officials, CIA agents began operating in Azerbaijan, then moved covertly into Dagestan and Chechnya, laying the groundwork for insurgency.

Fighters, funds, and ideology flowed in through unofficial channels, but always with strategic direction. What unfolded next wasn’t simply a rebellion—it was a manufactured proxy war, and in classic Gladio fashion, the United States was playing both sides.

Radical fighters—Mujahideen veterans from Afghanistan—were imported under the guise of “freedom fighters.”

These militants, financed and funneled through CIA-affiliated programs, were reportedly aided by Saudi intelligence with full U.S. approval.

Osama bin Laden, himself a former CIA asset during the Soviet-Afghan war, appointed his jihadist lieutenant Ibn al-Khattab as military commander in Chechnya. Bin Laden funneled millions of dollars per month to commanders like Shamil Basayev, pushing out moderate voices and militarizing the separatist movement beyond recognition.

Former FBI agent Ali Soufan stated plainly:

“The United States was on the Muslim side in Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Chechnya. And Muslim forces were supplied with weapons, money, and all necessary means.”

The insurgency became international.

MEGA Oil, under CIA-linked leadership, was accused of training jihadists, moving them across borders via Air America-style flights, and even delivering “brown bags” of cash to Azeri officials to smooth the pipeline’s path. Another staging ground was located in Turkey, a NATO member, from which fighters and equipment were funneled into the Caucasus.

It should be noted that Turkey had already had their own regime change through Operation Gladio back in the 80s. According to Turkish journalist, Mehmet Ali Birand, NSC (National Security Council) Advisor Paul Henze said in an interview that “Our boys did it.”

This Gladio unit known as “Counter-Guerilla” operated out of the Seferberlik Taktik Kurulu, or STK. The STK, in 1994, became the Special Forces Command (Turkish: Özel Kuvvetler Komutanlığı, ÖKK).

But the most striking example of Gladio’s Strategy of Tension was the case of Rezvan Chitigov.

After living in the United States, he returned to Chechnya in 1994 and claimed to have graduated from a U.S. sabotage and reconnaissance school, even serving on contract in a U.S. Marine battalion. He took a leading role in the separatist government’s military intelligence unit under Aslan Maskhadov. Locals nicknamed him “Amerikanets” (the American) and “Morpekh” (the Marine).

Later, Russian authorities accused Chitigov of planning to use chemical and biological weapons, including ricin, which was found in a hidden base in Gudermes.

This earned him a third alias: “Khimik” (the Chemist).

According to the Russian FSB, Chitigov was behind the 1999 bombing of Moscow’s Manezh shopping mall, was responsible for at least 50 civilian deaths in the Shali district, and maintained active ties with foreign intelligence agencies, including suspicions that he was himself a CIA asset.

So while the U.S. publicly denied Chechnya’s right to independence, it covertly empowered the very forces that tore the region apart.

America was playing both sides.

Create the threat.

Deny the outcome.

Bleed the adversary.

According to Yossef Bodansky, then-director of the U.S. Congressional Task Force on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, the U.S. was actively involved in “another anti-Turkish jihad, with the intention of supporting and strengthening the most poisonous anti-Western Islamist forces”.

outlines this pretty clearly in this thread.Putin saw the writing on the wall. And he was pissed.

"In my view, the important thing is that upon us fell the absolutely lasting opinion that our American partners speak about supporting Russia in words, they speak about their preparedness to cooperate, including in fighting terrorism, but in deeds they use these terrorists to unsettle the internal political situation in Russia.”

—Putin to Oliver Stone, The Putin Interviews

The Pipeline Wins, But at What Cost?

The war in Chechnya became brutal and unrelenting.

By the time Vladimir Putin rose to power in 2000, an estimated 8,000 Russian soldiers had died in the First Chechen War, with another 13,000 falling in the Second. But Russia prevailed—militarily, at least.

The insurgency was crushed, and Putin’s popularity soared.

But the war had already served its purpose.

The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, the goal all along, was completed in 2006, running through Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, neatly avoiding Russia.

Mission accomplished.

In a 2009 interview, Chechnya’s leader Ramzan Kadyrov, who was initially with the Chechen Independence movement, accused Western intelligence of orchestrating the entire conflict to fracture Russia.

“We are fighting against the forces of the United States and the British intelligence services... There was a terrorist, Chitigov, who worked for the CIA. When we killed him, I was in charge of the operation and we found a U.S. driving license and all the other documents were also American.”

The West blames Russia for authoritarianism. But when pipelines, power, and profit are at stake, who’s really pulling the trigger?

Putin’s Russia: Authoritarian or Just Sovereign?

Under Putin, Russia has undeniably centralized power—but it has also experienced economic recovery, higher birth rates, infrastructure growth, and a resurgence of national pride.

Between 1999 and 2008, Russia's GDP grew by 94%, with the economy's value rising from $210 billion to a peak of $1.8 trillion in 2008.

The proportion of Russians living below the poverty line decreased from 30% in 2000 to 14% in 2008. In 2023, the poverty rate further declined to 9.3%, with 13.5 million individuals below the poverty threshold, down from 14.3 million the previous year.

During Putin's first eight years, real incomes more than doubled, and the average monthly salary increased from $80 to $540. The middle class expanded from 8 million individuals in 2000 to 55 million in 2006, accounting for 37% of the population.

From 1999 to 2008, Russia’s GDP grew by at least 4.7% each year. This expansion made Russia one of the fastest-growing economies.

In 2001, a flat tax rate of 13% was introduced, simplifying the tax system and encouraging compliance. By 2005, Russia had repaid it’s $3.33 billion debt to the IMF (yes, the same IMF that was aware that Russia's Central Bank had been diverting funds into offshore accounts during President Boris Yeltsin's tenure).

While elections over there are maligned by various groups, they are popular within Russia, where national security and economic stability often outweigh pluralism in the public mind. Not ironically, the Communist candidate finished second in every case:

Nikolai Ryzhkov in 1991

Gennady Zyuganov in 1996, 2000 and 2008 and 2011

Nikolay Kharitonov in 2004

Pavel Grudinin in 2018

And the bottom line: Who are we to decide Russian election processes?

The West is not the world’s policeman.

So, is Russia still communist?

No. Not even close.

The Communist Party exists as a minor opposition faction, but modern Russia is nationalist, capitalist, and Orthodox Christian in character—a far cry from the Marxist atheism of the USSR.

Military Activity: The Villainy That Wasn’t

So what has Russia actually done militarily since 1991?

Chechnya (1994–2000): A brutal internal conflict, but one aimed at maintaining territorial integrity—not foreign conquest.

Georgia (2008): Russia intervened after Georgia launched a military offensive into the breakaway region of South Ossetia, where Russian peacekeepers were stationed.

Ukraine (2014, 2022): The annexation of Crimea followed the U.S.-supported ousting of a democratically elected pro-Russian president. The 2022 invasion is condemnable—but even here, the Russian narrative is about NATO encirclement and ethnic protection, not imperial ambition.

You can learn more about that last part here:

Have they invaded countries?

Yes—but far fewer than the United States, whose post-Cold War record includes Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, and covert operations across Latin America and Africa.

Nuclear Rhetoric: Who’s Actually Threatening?

Has Russia threatened nuclear war?

Occasionally—but almost always in response to Western escalations.

Since the '90s, NATO has crept closer to Russian borders, deploying troops, missile systems, and nuclear-capable assets in what was once considered a neutral buffer zone. Western leaders have openly discussed regime change in Russia, something that would be unthinkable if the roles were reversed.

The threat of nuclear war isn’t coming from Moscow alone—it’s a mutual, dangerous dance between superpowers, and one in which the West is hardly innocent.

Borders and Visas: Who's Closing the Doors?

Has Russia banned Americans from visiting? No—at least not until recently, and even then it’s been more retaliatory than aggressive. In fact, for decades, Russia welcomed tourists, students, and even journalists.

Compare that to the U.S., where visa restrictions for Russians tightened significantly even before 2022.

Western tech platforms and financial systems have blocked everyday Russians more than the Russian government has blocked everyday Westerners.

So... What Makes Russia the Great Evil?

They’re not communist. They’re not invading the globe. They’re not exporting ideology or forcing regime change in foreign nations.

In fact, a joint poll by World Public Opinion in the US and Levada Center in Russia around June–July 2006 stated that:

Neither the Russian nor the American publics are convinced Russia is headed in an anti-democratic direction.

A March 2005 survey of attitudes toward democracy shows that three times as many Russians feel that the country is more democratic today than it was under either Mikhail Gorbachev or Boris Yeltsin. The same proportion of the population rates humanrights conditions better under Putin than under Yeltsin.

So where’s the fire?

Russia isn’t threatening the world order.

It’s threatening the world order's monopoly—on narrative, on finance, on force. A nation that refuses to kneel at the altar of globalism is inconvenient.

And so, it's cast as evil. Not because it wants to conquer the world, but because it refuses to be conquered by it.

For 70 years, the West has used Russia—first the USSR, then the Federation—as its mirror villain, its budgetary boogeyman, its eternal excuse. From Operation Gladio to Iraq to Ukraine, Russia has been the reason given for every act of Western overreach, even when the facts say otherwise.

Russia didn’t engineer coups in Latin America. It didn’t fund jihadist proxies in Chechnya. It didn’t lie about weapons of mass destruction.

The United States did.

Russia has its sins—undeniable and well-documented. But they are not unique. They are not unprecedented. And they are not justification for painting a nuclear-armed power as the source of all global evil while ignoring the far-reaching influence of Western intelligence, military expansion, and corporate opportunism.

If we truly care about democracy, transparency, and peace, we must be willing to look beyond the enemy we’ve been sold and ask—who profits when we stop questioning? Who gains when we keep pointing east?

Villains don’t always speak Russian.

Sometimes, they speak English—fluently.

Sometimes, they fly flags of freedom while holding knives behind their backs.

And sometimes, the monster isn’t at the gate.

It’s in the mirror.

FAQs

Why did General Patton want to invade the Soviet Union?

He believed the USSR would become a future threat and felt it was better to strike while they were still weak post-WWII.

What was promised to Russia after the Soviet Union collapsed?

Verbal assurances were made by U.S. officials that NATO would not expand eastward—promises later broken.

How did the Red Scare impact U.S. culture?

It created an atmosphere of paranoia, led to blacklists, and justified extreme surveillance and censorship.

Has NATO broken its promises to Russia?

While not formalized in treaty, multiple diplomatic records show verbal commitments that were not honored.

Is Russia really a bigger threat than other global powers?

Russia poses challenges, but it’s far from the singular threat it's often portrayed to be—especially compared to rising powers like China.