GATEKeepers Pt 3 | The 60s, 70s, and the CIA

Explore how Cold War-era programs like the NDEA and CIA-influenced policy shaped GATE education in the 1960s and 1970s. The deep state's role revealed.

What if your school counselor wasn’t just helping you plan for college—but also feeding a quiet war machine? What if the classes you were funneled into, the tests you were given, the “talents” you were praised for—weren’t really about you at all?

This is the hidden history of Cold War gifted education, where national security quietly stepped in and made the classroom its battlefield. While it looked like America was investing in its youth, what was really being built was an infrastructure for tracking, sorting, and grooming students—not for freedom, but for function.

In this third part of our GATEKeepers series, we dive deep into how the U.S. military-industrial complex and intelligence agencies shaped educational policy in the 1960s and 1970s. If you missed the first two parts, start here:

GATEKeepers Pt. 2 | The Origins of the GATE Conspiracy

What if I told you that those IQ tests, counselor referrals, and enrichment programs for “gifted” kids weren’t just about helping your child thrive—they were about protecting the nation?

The Cold War’s Educational Front Line

After the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957, the United States scrambled. It wasn’t just about rockets—it was about brains. The U.S. feared it was falling behind intellectually, and that fear birthed a new national project: turning schools into factories of talent in service of national defense.

Enter the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958.

On its face, the NDEA aimed to boost American competitiveness in science and language.

Underneath?

It became a backdoor for the intelligence community to enter academia.

As early as 1960, official reports spelled out a dual mission:

“The national interest requires… that the Federal Government give assistance to education for programs which are important to our defense.” (NDEA Report, 1960)

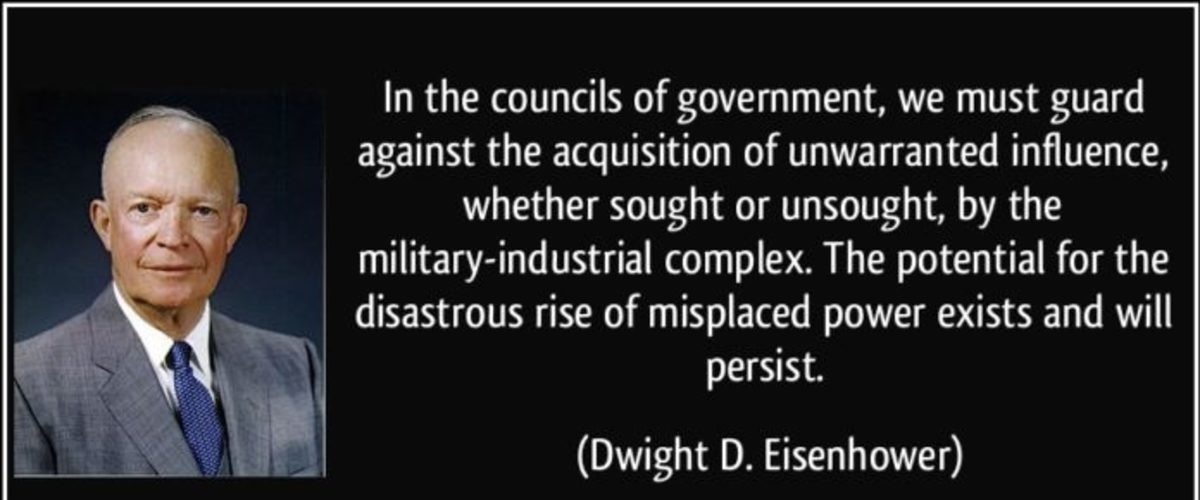

This wasn't about local control or personal growth. This was about weaponizing the mind. The military-industrial complex (Eisenhower’s warning in the following year, 1961) is the real client here, not the kids.

NDEA and the CIA: Building the Pipeline

The NDEA was massive. It poured federal money into testing, language programs, fellowships, and guidance counseling. But in the margins of that funding, something darker grew.

Cooperation Between the Office of Education and the CIA

In 1958, a letter from Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Arthur Flemming to CIA Director Allen Dulles spelled it out:

“Close cooperation between the Office of Education and the Central Intelligence Agency is indispensable.”

From the beginning, the Agency wasn’t just watching—they were building the program.

Monitoring NDEA Fellows for Recruitment

By 1962, the CIA’s Director of Training discussed using the rosters of NDEA language fellows (especially in Chinese) to identify candidates for recruitment. By 1965, they were actively tracking a CIA employee receiving an NDEA fellowship in Latin American Studies—monitoring her coursework and her timeline for returning to the Agency.

Academia had become a farm. The CIA wasn’t raiding schools—they were planting seeds.

CHINTELL and the Shape of Intelligence Education

In the 1970s, the CIA launched CHINTELL—a sweeping effort to fund and monitor 23 Chinese language and area studies programs, all through NDEA channels.

These weren’t just “culture” studies.

They were intelligence assets.

Columbia University alone had 303 China-focused graduate students, and the CIA had specific details on where exactly all the graduate students were in their East Asian Studies program.

Curriculum by Design: Shaping What Students Learn

The manipulation went beyond recruitment. Curriculum decisions were being influenced directly.

In 1958, less than 2 months after the passing of the NDEA, Adelphi College consulted with the CIA on which languages to include in its NDEA-supported program. In the margins, “Indonesia” is mentioned as being vital (the CIA had attempted a coup there about 6 months earlier). The CIA would go on to infiltrate the Indonesian government and society over the next 10 years. This document shows that the Agency’s input shaped which languages were taught, how courses were built, and which professors got funded.

Educational content was being engineered to meet intelligence needs. Kids thought they were studying to understand the world. The reality? They were studying to serve it—quietly, obediently, and often without even knowing it.

Counseling: The Soft Hand of Hard Power

One of the most understated but powerful tools in this Cold War education framework was the rise of guidance counseling. It seemed harmless. Helpful, even.

But look again.

From a 1960 NDEA counseling report:

“The right of a person to shape his own destiny takes precedence over the right of society to make use of his talents.

Fortunately, our long experience with the democratic system has demonstrated to us that there' need be no essential conflict here. The choice a person makes about what to do with his life, if it rests on thoughtful consideration of all the factors involved, represents a synthesis of his personal and social values.

The aim of counseling is to help each young person make good choices and plans. That is why it is such an essential part of our whole educational enterprise.”

Read between the lines. “Social values” didn’t mean community. It meant national need.

Counselors were trained to spot talent, funnel it, and steer it into the paths laid out by federal planning. The Rockefeller Brothers Fund nailed it in their 1960 education report (a report which was under the direction of Henry Kissinger).

“Identification of talent is no more than the first step. It should be only part of a strong guidance program... essential to the success of our system.”

Success of whose system?

Just look at who was on the panel:

Nelson A. Rockefeller: Chairman of the panel and later Vice President under Gerald Ford, Rockefeller was a central Cold War strategist with deep ties to U.S. foreign policy, propaganda, and intelligence-adjacent programs.

General Lucius D. Clay: Former Commander-in-Chief of U.S. Forces in Europe and Military Governor of postwar Germany.

Gordon Dean: Former Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission and senior VP at defense giant General Dynamics.

Anna M. Rosenberg: Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Personnel, she helped manage the military’s human capital.

Dean Rusk: Then-president of the Rockefeller Foundation and later Secretary of State during the Vietnam War (for which he was one its strongest supporters). He was also one of the two people who suggested splitting Korea into North and South Korea (The 38th parallel).

General James McCormack: Vice President at MIT and former Army officer. He was the first Director of Military Applications of the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

Edward Teller: Physicist known as the "father of the hydrogen bomb" and a key figure in U.S. nuclear weapons development. Was also involved in the Manhattan Project.

Henry Kissinger: Director of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund's Special Studies Project and later National Security Advisor and Secretary of State. Kissinger had close ties with the CIA, bridging the intelligence world with diplomacy. Among other things, he was associated with the bombing of Cambodia, involvement in the 1971 Bolivian and 1973 Chilean coup d'états, support for Argentina's military junta in its Dirty War, support for Indonesia in its invasion of East Timor, and support for Pakistan during the Bangladesh Liberation War and Bangladesh genocide.

These weren’t teachers dreaming of better lesson plans. They were Cold War power brokers—military brass, nuclear architects, intelligence liaisons, and global operators. The kind of people who didn’t just support foreign coups—they signed off on them.

So when they said talent needed to be “identified,” they weren’t talking about nurturing poets or free thinkers. They were talking about screening for usefulness.

Loyalty.

Obedience.

Strategic value.

And to do that?

They needed tests, data, and profiles.

Testing and Profiling: Data as Destiny

To build the system, you need data. Lots of it. And the Cold War gave birth to a testing frenzy that masqueraded as meritocracy.

Going back to the 1960 NDEA counseling report:

“Various psychological tests were used, both as selection devices and as a means of obtaining additional information about enrollees after they had been selected.”

Psychological profiling became standard. And this wasn’t even for the students yet. This was for the counselors.

Before you could even begin identifying gifted youth, you had to be cleared to do the identifying. The federal government didn’t want just any teacher advising the next generation of Cold War assets. They needed a new kind of gatekeeper—someone who could recognize strategic talent, maintain ideological alignment, and follow protocol.

Enter the Counseling and Guidance Training Institutes, launched under the NDEA. On the surface, these were designed to professionalize school counseling. But behind the brochure smiles and seminar pamphlets was something else entirely: a psychological filtration system.

Let’s break it down.

To judge whether a teacher or counselor was fit to become part of this federal talent-scouting corps, institutes administered a battery of academic and psychological tests:

Miller Analogies Test (MAT), Graduate Record Examination (GRE), and Concept Mastery Test: These weren’t just academic hurdles. They screened for abstract reasoning, pattern recognition, and verbal acuity—traits highly valued in intelligence analysis, not just guidance counseling.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI): This was the gold standard of psychological profiling. Used heavily in clinical and government settings, it looked for neuroticism, paranoia, and emotional instability. The government wanted to ensure these counselors were stable—but also controllable.

Strong Interest Inventory and the Kuder Preference Record: These tools mapped individual interests and occupational leanings. In other words, they helped assess how willing a counselor might be to align with the broader mission—be it defense, state goals, or quiet compliance.

Allport-Vernon-Lindzey Study of Values and Minnesota Teacher Attitude Inventory: These were tools for ideological mapping. Was the applicant more theoretical or economic in their values? More religious, more authoritarian, more “loyal”? These tests hinted at alignment with prevailing Cold War ideologies.

And then there were the standardized case studies, like The Case of Mickey Murphy or The Case of Barry Blake. These weren’t just hypothetical scenarios—they were psychological field exercises. The idea was to measure how prospective counselors responded to complex student situations. But there was another layer: empathy calibration. Counselors who were too emotionally reactive—or not reactive enough—could be flagged.

Because again: this wasn’t just about guiding students. It was about managing them.

Data Without a Scantron: The Nontest Methods

If the tests didn’t catch every detail, the Institutes had plenty of other tricks.

Roleplay evaluations: In some cases, the "student" wasn’t a student at all, but an actor playing a standardized role. The counselor didn’t know it. This is similar to most medical schools today (nearly 90%) who use actors to portray patients with different medical conditions. This was an effective conditioning exercise so that counselors would instintively learn what signs to look for.

Autobiographies: At several institutes, participants had to write life stories—framed as “self-understanding” exercises. These could be used to build psychological profiles from the ground up. Family background. Ideological leanings. Moments of trauma. All of it was mined, cataloged, and assessed.

Q-sorts, sentence completion tests, and situational tests: These exercises required enrollees to rank values or complete unfinished thoughts.

The Q-sorts (“mostly agree” vs “"mostly disagree” and options in between, for example) are not exercises for the counselor, but for those analyzing the counselors. It gives them insight into how the counseling enrollees think and their viewpoints on certain subjects. These types of assessments were designed to “to reveal the respondent’s conception of counseling.” Based on what they really want out of their enrollees, they could then modify the curriculum to learn towards what their viewpoints should be.

In many places, these sort of "postselection assessment procedures” would follow a before-and-after design “so that the effects of institute experience could be appraised.”

Before the government trusted you to work with “gifted and talented” students—kids who might someday hold state secrets, design weapons, or conduct diplomacy—it needed to know you wouldn’t rock the boat. That you would recognize the “right” kind of brilliance. That you’d guide talent not toward self-fulfillment, but toward utility.

The GATE program would soon be born out of this structure.

They built the gatekeepers before they built the gate.

Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965): Infrastructure for Control

Then came LBJ’s ESEA, the original blueprint for federal oversight in public education. Again, the language was hopeful:

“To strengthen and improve educational quality and educational opportunities in the Nation’s elementary and secondary schools.”

But buried in Title V, Sec. 503? Grants for state-level data collection and program development.

“Providing support or services for the comprehensive and compatible recording, collecting, processing, analyzing, interpreting, storing, retrieving, and reporting of State and local educational data, including the use of automated data systems.”

The foundation of gifted identification systems which would come later.

The Shape of Things to Come

By the end of the 1960s, the U.S. education system was transformed. On the surface, it still looked like local school boards, school counselors, and state departments were in charge.

But behind the curtain, the federal government—guided by military and intelligence priorities—had built a machine: a pipeline that began in first period algebra and ended in D.C. think tanks, black-budget labs, and overseas posts.

They didn’t need to control every teacher. They just needed the infrastructure:

Counselors trained to spot “potential”

Tests designed to sort the loyal from the unpredictable

Grants that nudged schools into compliance

And just as this Cold War machine was reaching maturity… the Marland Report dropped in 1972.

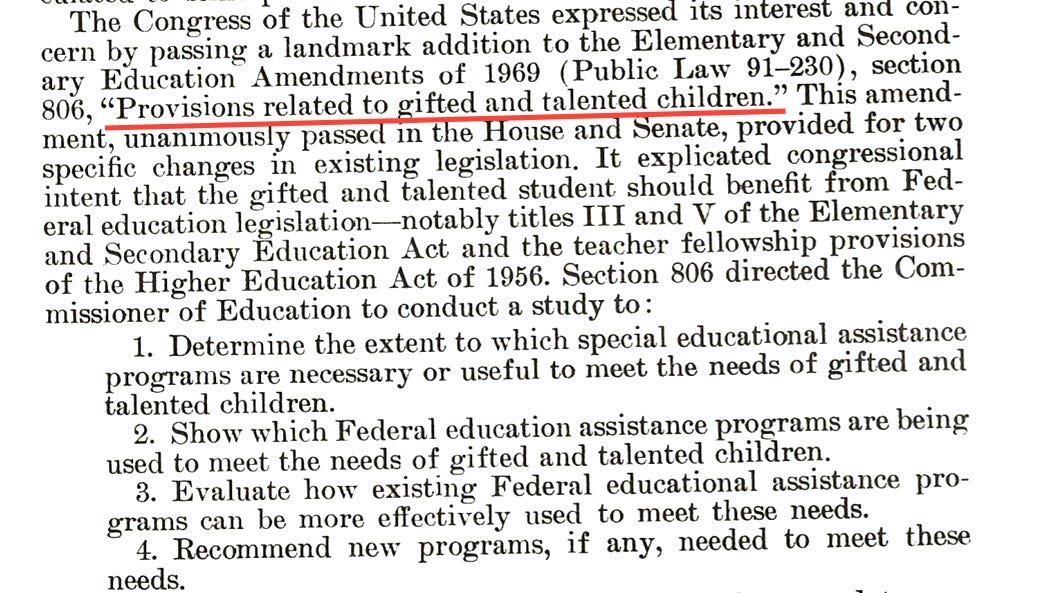

The Marland Report

The Marland Report was a federal report by U.S. Commissioner of Education Sidney P. Marland, Jr., mandated by the Education Amendments of 1969. Submitted in 1971, published 1972, it’s the first national push to define and prioritize gifted education—GATE’s origin story.

Jane Case Williams, daughter of congressman Francis H. Case, oversaw the planning, coordination, and direction of the study for analyzing gifted children.

Strangely, there is no evidence that she was ever a classroom teacher.

Her federal career began in the central office of the Head Start Program of the Office of Economic Opportunity, a centerpiece of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. But her real training came under what she described as the tutelage of “the legendary Jule Sugarman.”

And Sugarman? That’s where things start to echo.

He was military during WWII—like many of the men quietly guiding federal education policy. But more specifically, Sugarman served in the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA)—the same intelligence-adjacent agency Nelson Rockefeller ran during the war.

For Soviet intelligence, the OIAA wasn’t just another American office. According to decrypted communications from the Venona Project, the Soviets gave the OIAA the codename “Cabaret”, suggesting they viewed it as a likely front for U.S. espionage.

So yes, the man Jane Williams called “legendary” worked in what appears to be an intelligence-linked propaganda bureau.

And then she was tasked with analyzing gifted children.

After the report was completed, the federal government didn’t just read it—they institutionalized it. The Office for Gifted and Talented (OGT) was established within the U.S. Office of Education, and Williams was installed as an executive. The project had moved from study to strategy.

And the report itself? It wasn’t subtle.

“A conservative estimate of the gifted and talented population ranges between 1.5 and 2.5 million children… of 51.6 million.”

Translation: 3–5% of American students were now flagged as national assets.“The education of the gifted and talented is not a luxury; it is a necessity for the survival and prosperity of the Nation.”

That’s not a mission statement. That’s a national security doctrine.

The Marland Report didn’t just suggest improving enrichment programs. It called for:

Federal planning reports to implement a national gifted strategy

Leadership training institutes to professionalize GATE administration at the state level.

Permanent federal leadership to ensure gifted education remained a “national priority”.

And why?

"The gifted and talented are a national resource, and their identification and proper education are essential to the welfare of the Nation."

“Without a doubt, [the children] who will make the greatest contribution to society, they who will provide the leadership and the brainpower...they are the gifted.”

The message couldn’t be clearer: gifted children were no longer just students. They were strategic resources—intellectual troops in a war for cultural, technological, and geopolitical dominance.

And if any doubt remained about the lineage of this program, the report made the connection explicit:

“Although the National Defense Education Act of 1958 does not specifically mention gifted and talented children… it does fund strengthening of instruction in science, mathematics, modern foreign languages…[the NDEA] views top-grade instruction in these areas as critical to the protection of this country, and by implication, the development of students gifted or talented in these areas as a national resource to be developed. This act could be part of a delivery system for the gifted and talented.”

A delivery system.

Not for food.

Not for healthcare.

For children.

Children identified, tracked, tested, and placed on rails built not by teachers, but by military strategists, psychological profilers, and Cold War planners.

The NDEA planted the seeds.

The Marland Report harvested the field.

The GATE had opened.

And the nation’s most “gifted” children were already walking through it—whether they knew it or not.

MKULTRA and the GATE Program

At first glance, there’s no reason to link a government-run gifted program with a covert mind control project.

One wears a lab coat.

The other wears a badge.

One claims to nurture potential.

The other was designed to erase or rewire it.

But look beneath the surface, and the timelines begin to blur.

The methods overlap.

And the purpose—national interest, defense, control—remains the same.

The Secret History Beneath the Surface of Public Policy

While Americans saw a flurry of federal educational reform in the 1950s and 60s—starting with the National Defense Education Act (1958), followed by the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965), and later the creation of the Office of Gifted and Talented (OGT) in 1972)—a parallel operation was unfolding in the shadows.

That operation began in 1950 with Project BLUEBIRD, was renamed Project ARTICHOKE a year later, and finally became MKULTRA in 1953.

The goal? Simple in theory, horrifying in practice:

To explore how to control human behavior.

Through drugs.

Through psychological conditioning.

Through trauma.

Funded and run by the CIA, MKULTRA would experiment on hundreds—possibly thousands—of people across the U.S. and Canada, often without their consent.

Hypnosis, LSD, electroshock, sensory deprivation, abuse—it was all on the table.

These programs weren’t exposed until 1975—25 years after they began, and 10 years after they were “allegedly” stopped. Even then, most of the documentation had already been destroyed. If what we know about the program is so horrific, you can only imagine what was in the files that were destroyed.

Lining Up the Timelines

Now compare the official education timeline:

1950–53: BLUEBIRD, ARTICHOKE, and then MKULTRA are launched. MKULTRA oversees subprojects exploring LSD, sensory deprivation, trauma-based conditioning, and psychological programming.

1957: Sputnik is launched by the USSR. Widespread panic in U.S. education and defense sectors.

September 1958: NDEA is passed. Funds psychological testing, counselor training, language programs, and student tracking systems. Begins federalizing education.

October 1958: Less than 2 months after NDEA’s passage, Adelphi College consults the CIA on which foreign languages to include in its NDEA-funded curriculum.

1957: Dr. Donald Ewen Cameron began his notorious experiments in “psychic driving” at the Allan Memorial Institute through MKUltra’s Subproject 68.

1958: Letter from Secretary of HEW Arthur Flemming to CIA Director Allen Dulles confirms:

“Close cooperation between the Office of Education and the Central Intelligence Agency is indispensable.”

1959: MKULTRA Subproject 103 is underway. The CIA secretly studied children as young as 11 in three Texas cities at summer camps. Allegedly, it was to identify potential recruits for the Agency.

1960: NDEA Counseling Report published:

“The aim of counseling is to help each young person make good choices and plans… for both personal and social values.”

1960: Rockefeller Brothers Fund’s Special Studies Project, directed by Henry Kissinger, releases its education report. Nearly every panelist had military, defense, or intelligence roles.

“Identification of talent is no more than the first step… essential to the success of our system.”

1960: Dr. Lauretta Bender gets funding through the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology (SIHE) for LSD experiments on children, ages 6-10. SIHE was a CIA front group, which also funded Dr. Cameron.

1962: CIA Director of Training discusses using NDEA rosters—particularly Chinese language fellows—for recruitment into intelligence. NDEA becomes a scouting tool.

1964: Dr. Donald Ewen Cameron left the Allan Memorial institute and his psychic driving experiments.

1965: ESEA is enacted—expanding federal involvement in local schools and laying the groundwork for later gifted programming.

1972: The Marland Report leads to the creation of the OGT, and gifted children are officially reclassified as a “national resource.”

These two timelines didn’t just run parallel—they intersected in method, mission, and sometimes, in people.

While MKULTRA was experimenting with behavior modification in secret labs, the federal government was quietly normalizing psychological screening, data profiling, and behavioral assessments in schools under the banner of "gifted education."

Shared Methods: Creeping Parallels

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable.

The techniques used to shape GATE bear striking similarities to those used in MKULTRA.

Behavioral Analysis: MKULTRA tested how people responded to stress, stimuli, and controlled environments. GATE began using similar psychometric tools to evaluate how “gifted” children thought, behaved, and adapted—often starting in elementary school.

Psychological Testing: MKULTRA (Subproject 134) used the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) to evaluate and sort subjects. So did GATE’s counselor training institutes.

Data Collection and Dossiers: MKULTRA created detailed psychological profiles on subjects. GATE, backed by NDEA and ESEA provisions, created tracking systems for students.

“The comprehensive and compatible recording, collecting, processing, analyzing, interpreting, storing, retrieving, and reporting of State and local educational data, including the use of automated data systems.”

—ESEA, Title VManipulating the Vulnerable: MKULTRA targeted the voiceless—orphans, prisoners, patients in state hospitals. Later, GATE began expanding access to “disadvantaged but high-potential” students (Talent Search Program)—a seemingly noble goal that also gave the state access to bright children from economically dependent families. Kids with fewer exits.

Framing it as National Security: MKULTRA operated under the Cold War doctrine of “survival.” So did GATE. The Marland Report made this explicit:

“The education of the gifted and talented is not a luxury; it is a necessity for the survival and prosperity of the Nation.”

MKULTRA used LSD. GATE used diagnostics. And maybe other stuff (we’ll find out in Part 4)

But the purpose wasn’t that different.

Understand the brain. Shape the mind. Serve the system.

Denial, Delay, Disclosure: What MKULTRA Taught Us About “Impossible” Truths

If any part of this seems far-fetched, let’s pause.

MKULTRA was not revealed until 1975, after a series of leaks and congressional investigations. The public was stunned—but the Agency shrugged. Most of the files were destroyed in 1973 by order of then-CIA Director Richard Helms.

What remains are fragments.

We know children were experimented on.

We know that orphanages, psychiatric wards, and schools were used as test sites.

We know the CIA used euphemisms like “behavioral research” and “psychiatric support” to mask brutal manipulation.

If they did this once—and they did—it’s not outlandish to wonder what else might have been built on those same bones.

Or what was in the destroyed files.

The Next Chapter: When GATE Became the Petri Dish

By the 1980s, the GATE program expanded nationwide.

By the 1990s, it tightened its filters and added advanced behavioral diagnostics.

By the 2000s, it wasn’t just about intelligence—it was about tracking aptitude, response time, personality metrics, leadership traits, and risk assessment.

GATE began to look more and more like a state-run lab—one that screened and tagged children not just for enrichment, but for potential future roles.

Leadership. Innovation. Control.

What if the kids being labeled “gifted” weren’t just bright?

What if they were selected?

We’ll explore this evolution in GATEKeepers Pt 4: The Profile of a GATE Student

You’ll want to read that with the lights on.